The factors that affect human health differ significantly between more and less developed nations.

Back in 1995, when Sudan was still one nation with two warring factions—north versus south—Nabil Aziz Mikhail bore witness to a quiet sort of miracle.

The country’s Ministry of Health had long reported Guinea worm cases in the low thousands. But Mikhail, who had just assumed the role of Guinea Worm Eradication Coordinator, had quickly discovered that the number was much, much higher than that: A better estimate was 100,000-plus cases. Mikhail knew that simple measures, such as those the Carter Center was employing elsewhere, could stop the disease in its tracks. But he also knew that no such measures could be employed in Sudan, marred as it was by poverty and extreme violence. The most afflicted areas were simply too dangerous to venture into. Even if they could be reached, eradication programs—community education, latrine building, even pesticide application—would be impossible to implement under the circumstances.

91

KEY CONCEPT 5.7

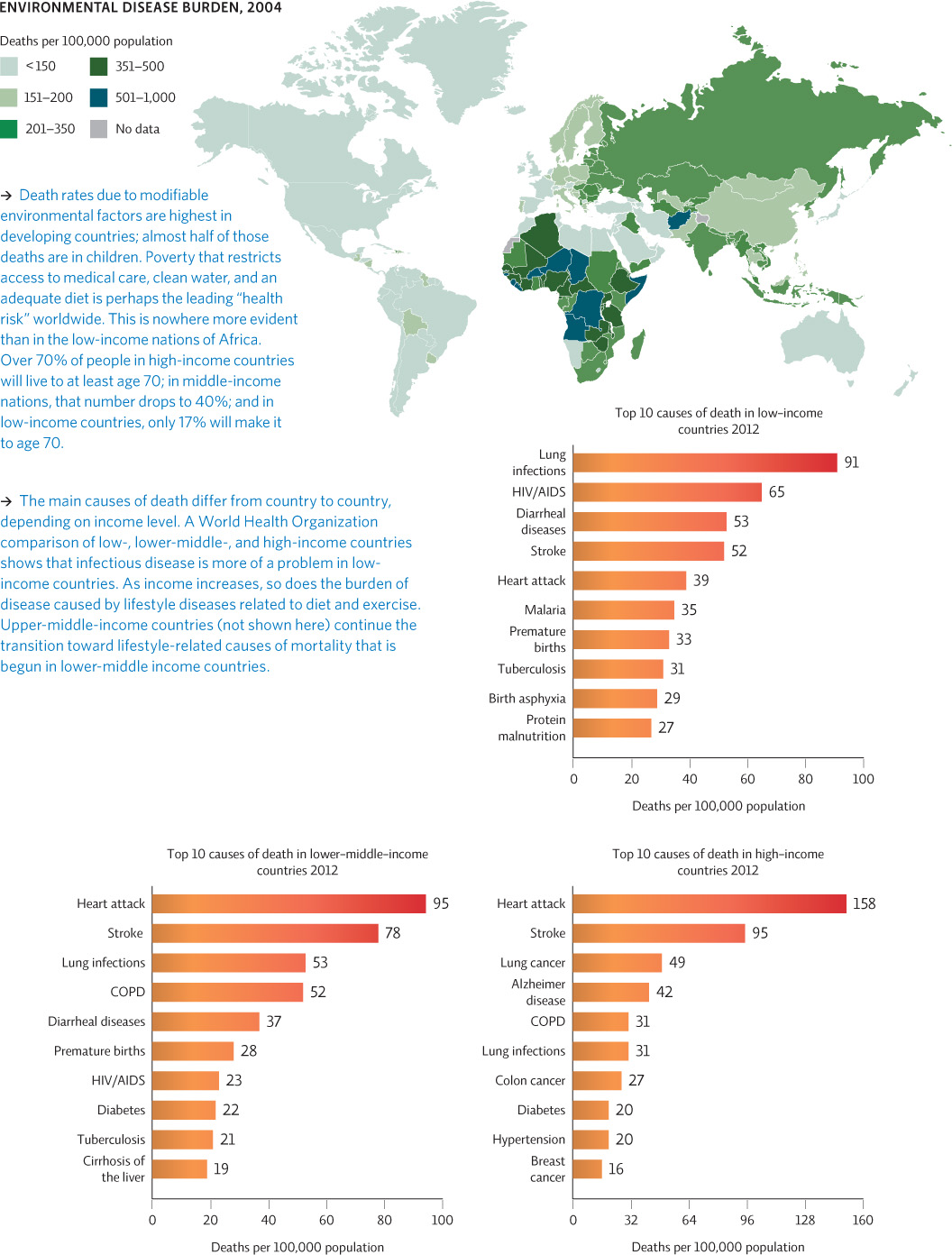

People in wealthier nations are more likely to die from life-style diseases, whereas in low-income countries, the leading causes of death are infectious diseases, many of which are linked to poor environmental conditions.

Here’s where the miracle comes in: Desperate to make a dent in the problem, Mikhail and his colleagues called former U.S. President Jimmy Carter and invited him to host a conference on GWD in their war-torn home. Carter went a step further: Not only did he come to Sudan, but he quickly negotiated what would later be called the “Guinea Worm Cease Fire”—a laying down of arms that lasted 6 full months and allowed public health workers to secure unprecedented gains in the region. Infected water sources were detected and decontaminated, filters were distributed, and active infections were treated—on a scale the country had never seen before. “It was a dream,” Mikhail says now. “I’ve never heard of a health activity that brought any sort of cease-fire.”

It was also a lesson, Mikhail says: If there’s one human behavior that favors the Guinea worm even more than bathing in infested water, it’s war. Plain and simple.

In fact, war is just one reason that the death rate from environmentally mediated diseases is much greater (12 times greater, in 2006) in less developed nations than it is in more developed ones. Poverty is another; poor basic nutrition is another still.

As we discuss elsewhere in this book, the differences between more developed and less developed countries are vast. In more developed countries, cardiovascular disease and cancer represent the bulk of the disease burden. (These are caused by lifestyle choices and industry and vehicle pollution.) In less developed countries, while NCDs are ticking upward, infectious diseases, caused by all the environmental factors we’ve already discussed (e.g., lack of clean water, poor sanitation, burning of solid fuels indoors for heat and energy), are still the leading cause of death. INFOGRAPHIC 5.6

DEATH RATES AND LEADING CAUSES OF DEATH DIFFER AMONG NATIONS

Why do you think middle-income nations suffer both from lifestyle factors and from infectious diseases like diarrheal diseases and tuberculosis?

As income increases, a shift to a more western diet occurs (higher in fat and sugar) and perhaps a shift toward a more sedentary lifestyle. But public health programs and protective infrastructures (i.e. safer roads, better sanitation) are probably not as common as in wealthier countries so rates of infectious disease and injury are still higher.

The Sudan cease-fire gave health workers a fighting chance to address the environmental conditions that favored Guinea worms. “Once the violence stopped, progress was imminent,” says Ruiz-Tiben. “The Sudanese health workers and foreign nongovernment organizations surprised themselves with what they were able to accomplish in those 6 months. But when the cease fire ended, the infection rates climbed right back up.” Today, though South Sudan became an independent nation in 2011, violence persists and has left the country one of the few still plagued by GWD. The number of infections in South Sudan is beginning to fall once again, from 521 cases in 2012 down to 113 cases in 2013. Those 113 South Sudan cases represented 76% of the world’s GWD cases in 2013; the remaining 35 cases were reported in Chad, Ethiopia, and Mali.