Mainstream economics supports some actions that are not sustainable

Current-day, or “mainstream,” economics allows managers to evaluate possible resource-use choices and make the most profitable decisions, often by seeking to maximize value—that is, achieving the greatest benefit at the lowest cost. However, one of the complaints against mainstream economics is that it doesn’t take into account all potential costs when trying to maximize value. For instance, a carpet tile might require a certain amount of material that has a particular monetary cost; but what about the environmental costs associated with drilling enough oil to make that material in the first place, or the costs associated with cleaning up the pollution it creates?

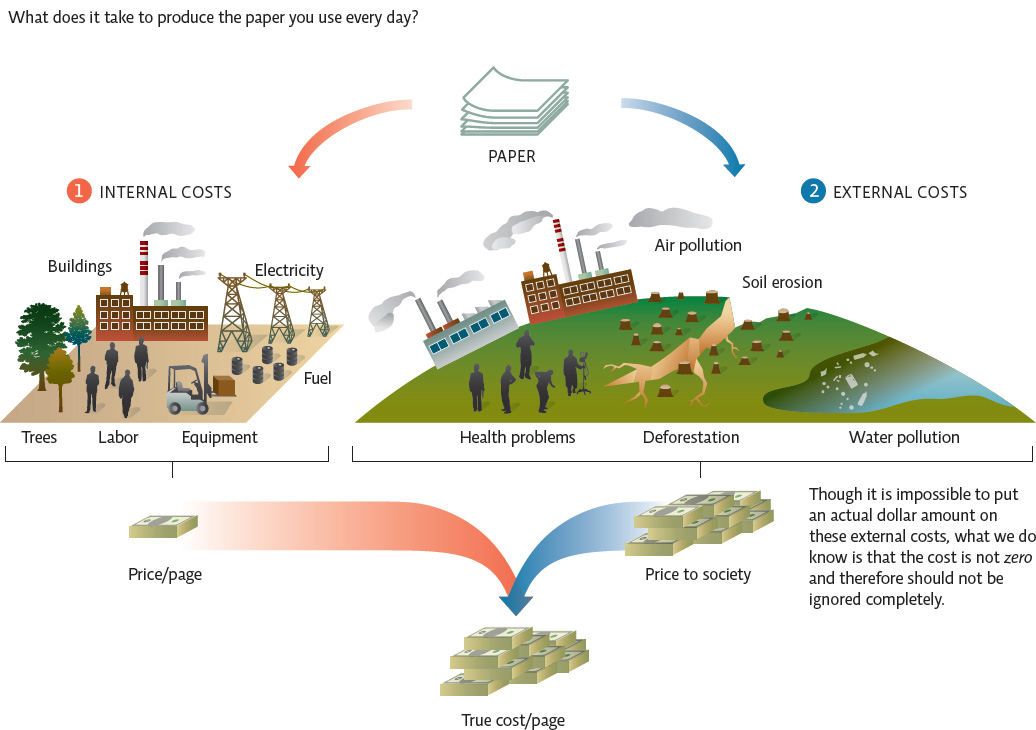

The direct cost of the material is an internal cost—a cost that is accounted for when a product or service is priced—but it is often incomplete. There can also be external costs, such as the health costs associated with the waste produced by making the carpet tiles or the environmental damage caused by pollution. Historically, economists have regarded these as external to the business (the business doesn’t pay for them), and they aren’t reflected in the price the consumer pays for the good or service. But if the business doesn’t pay for the costs or pass those costs on to the consumer, who does pay? Other people, present and future, and other species do. They pay in the form of degraded health, ecosystems, or opportunities.

internal cost

A cost—such as for raw materials, manufacturing costs, labor, taxes, utilities, insurance, or rent—that is accounted for when a product or service is evaluated for pricing.

external cost

A cost associated with a product or service that is not taken into account when a price is assigned to that product or service but rather is passed on to a third party who does not benefit from the transaction.

106

An assessment of the cost of a good or service (or any of our choices) should include more than just the economic costs; it should also include the social and environmental costs—the triple bottom line. By ignoring the external costs, economies create a false idea of the true and complete costs of particular choices. A customer may pay $8 for every 50-square-centimeter (about 8 square inches) carpet tile, but the true cost for that piece of carpet would be much higher if it included the cost of greenhouse gas emissions and, for instance, the cost of treating people for asthma if they have fallen ill as a result of the particulate matter released during the carpet’s production. The inadequate valuation of a product could eventually lead to the exploitation or overuse of resources needed to produce it—an example of market failure. When external costs are internalized, on the other hand, people (or species) who don’t benefit from the transaction do not pay for it. In this case, the product or service can be more appropriately priced or valued; this new price more accurately reflects the true cost of the product or service.

triple bottom line

The combination of the environmental, social, and economic impacts of our choices.

true cost

The sum of both external and internal costs of a good or service.

KEY CONCEPT 6.5

The price of a product usually reflects only the internal costs of doing business, not the social and environmental external costs. This means those costs are not passed on to the consumer but rather are paid by others. Internalizing these external costs better reflects the true cost of a product.

Because we are so accustomed to not paying true costs, we would most likely be appalled at how much goods and services would really cost if all externalities were internalized. Although it sounds discouraging, any time we purchase products that were made in a more environmentally or socially sound manner, we come a little closer to bearing the consequences of our choices. We also create a demand for these products in the marketplace. And, if businesses are forced to internalize external costs, it then becomes profitable for them to take steps to lower those costs—for example, by installing pollution prevention technologies—a benefit that could lower the environmental and societal costs overall. INFOGRAPHIC 6.5

TRUE COST ACCOUNTING

Many environmental and health costs of our goods and services are externalized (not included in the price the consumer pays). But if consumers don’t pay all the costs to produce a product, such as paper, who does?

What could a paper company do to reduce the external costs of harvesting trees to make paper?

The external costs associated with deforestation could be reduced if forests are harvested sustainably or if other sustainable raw materials are used instead of trees, including recycling. Water pollution could be reduced or avoided with technologies that capture pollutants or use less (or non-) polluting procedures.

107

KEY CONCEPT 6.6

Ecological economists argue that mainstream economics will fail in the long run because it makes some assumptions that are inconsistent with the way nature operates.

Ecologically minded economists are considering how to incorporate environmental considerations into economic decisions. Ecological economics is a discipline that considers the long-term impact of our choices on human society and the environment. With this focus, ecological economists argue that mainstream economic theory will fail because it is based on several erroneous assumptions.

ecological economics

New theory of economics that considers the long-term impact of our choices on people and the environment.

One inaccurate assumption of mainstream economics is that natural and human resources are either infinite or that substitutes can be found if needed. This is true for some but not all resources. For instance, fossil fuels are finite and will run out, even with technological advances that allow us to access more of the fuel that is left. It remains to be seen if we can replace fossil fuels with sustainable alternatives at current levels of use. In addition, our actions can degrade air and water resources faster than nature can restore them; also, crop productivity has limits.

Mainstream economics also assumes that economic growth will go on forever. Since there are inherent limits to what Earth can provide, unlimited economic growth (at least that which depends on finite resources) is not, in fact, possible. We have to work within the limits of available resources in ways that allow essential ecosystem services to continue.

108

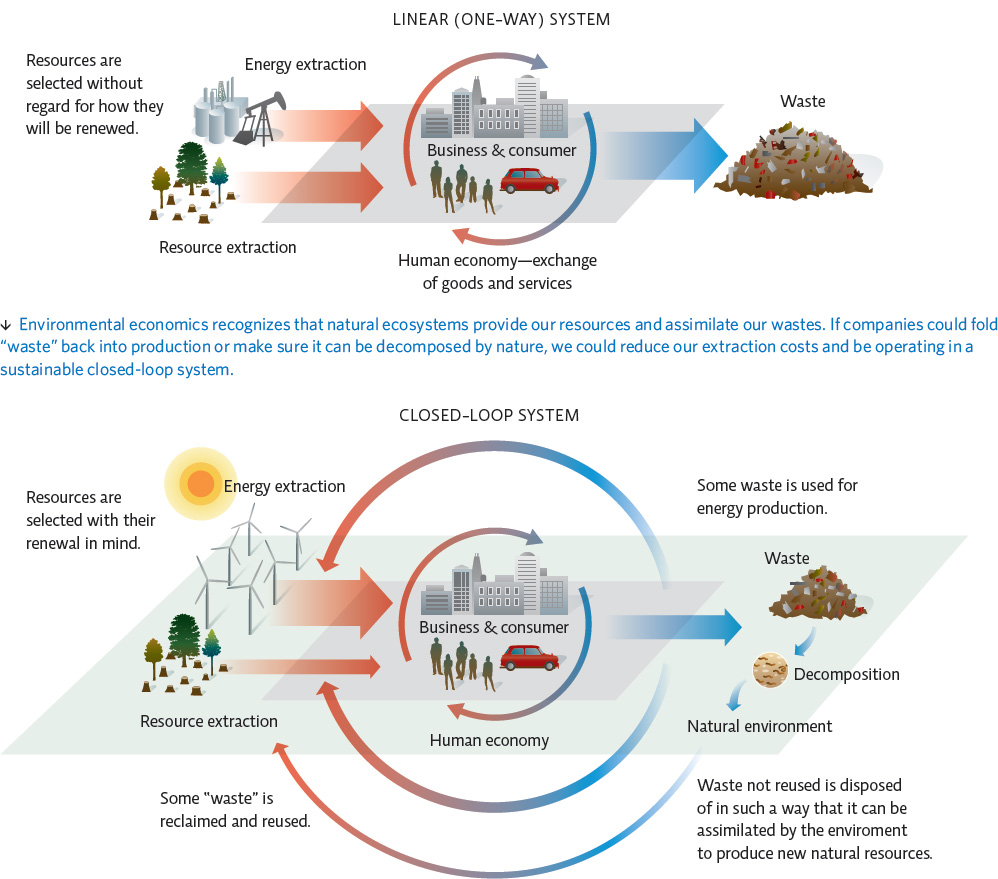

These assumptions lead to yet another misconception—that models of production follow a linear sequence: Raw materials come in, humans transform those materials into some kind of product, and then they discard the waste generated in the process. But because some resources are finite—and waste in the form of pollution can damage natural capital such as air, water, and soil—linear models of production will eventually fail. For instance, most traditionally produced carpet tiles are made from fossil fuels, a practice that is not sustainable. Old unwanted tiles are then discarded, and some are eventually burned, releasing toxic pollutants and greenhouse gases. A sustainable approach would be more cyclical, where “waste” becomes the raw material once again and can be used to make new products. Interface’s ReEntry 2.0 program uses old carpet tiles to make new ones, and it uses old carpet backings to make new carpet backings, in an effort to make the production process more cyclical. This is an example of a closed-loop system, where the product is folded back into the resource stream when consumers are finished with it or is disposed of in such a way that nature can decompose it. INFOGRAPHIC 6.6

closed-loop system

A production system in which the product is returned to the resource stream when consumers are finished with it or is disposed of in such a way that nature can decompose it.

ECONOMIC MODELS

Mainstream economics assumes that resources will always be available and that waste can be disposed of in a linear (one-way) system.

Look at the size of the arrows in these two diagrams. Which ones increase and which ones decrease in size? Why?

In the closed-loop system, the energy extraction arrow from sustainable sources is larger than the original fossil fuel arrow, indicating that we should decrease our use of fossil fuels and transition to sustainable sources of energy. The resource extraction arrow is much smaller in the closed-loop diagram than the linear model because much more of our resources would come from recycling. The waste arrow is smaller in the closed-loop diagram than the linear model because much more of the waste is diverted to be raw material for new products or fuel.

109

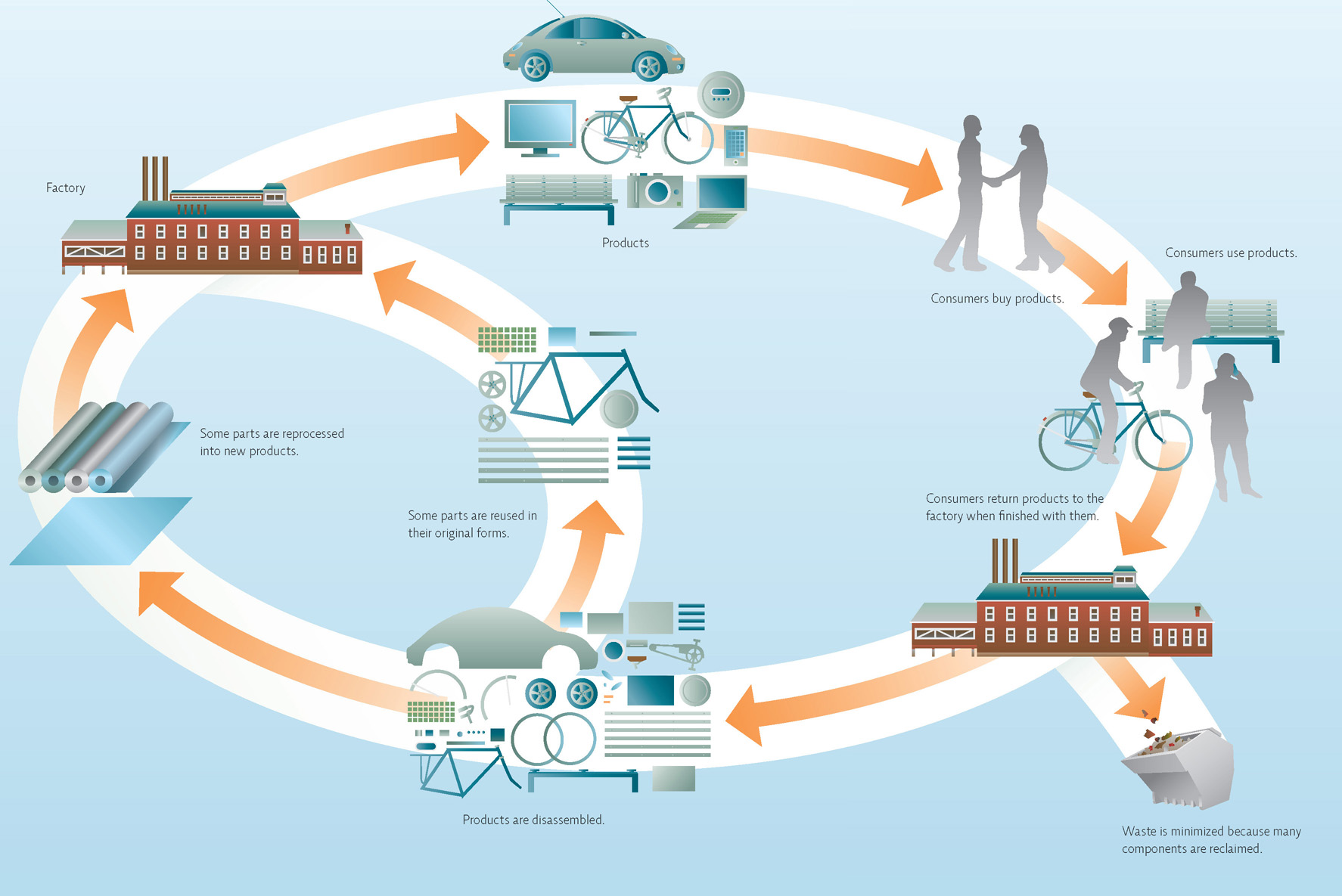

Interface seeks to operate as a closed-loop system by managing its product in a cradle-to-cradle fashion: It considers the entire life cycle of the product, from the beginning (acquisition of raw materials) to the end of its useful life (disposal), and is responsible for the impact of its use at every stage of the process. This can lead to better material choices (less toxic, more sustainable) and better process choices (reusable materials, less waste and pollution). INFOGRAPHIC 6.7

cradle-to-cradle

Management of a resource that considers the impact of its use at every stage, from raw material extraction to final disposal or recycling.

CRADLE-TO-CRADLE MANAGEMENT

In cradle-to-cradle management, the manufacturer is responsible for the product from its production (cradle) to its final disposition after the consumer is finished with it. If the item were merely disposed of, it would be sent to its “grave” and those resources wasted. If, however, the item is disassembled and the parts reused, these parts become raw material again for a new product—a new “cradle.” This provides an incentive to produce the product in a way that uses durable, reusable parts and that minimizes toxicity, since the manufacturer is responsible for dealing with those toxins.

Explain why this flowchart is an example of a cradle-to-cradle management system.

The product that is made (carpet) is captured after consumers use it and remade into new carpet. Thus it is managed from cradle (making the product) back to cradle (making new product from the discarded carpet) rather than cradle to grave (discard the carpet rather than find a use for it).

Another problem with mainstream economics is that it discounts future value: It tends to give more weight to short-term benefits and costs than it does long-term ones. In other words, mainstream economics considers something that benefits or harms us today more important than something that might do so tomorrow. For instance, we value the tuna we can harvest today more highly than tuna we might harvest 10 years from now, so the value of taking a large harvest of tuna today outweighs the benefits of taking less now to ensure that there is still some later. If the money we could earn by using the resource now is higher than sustainable harvesting yields, modern economics tells us it is more profitable to use it now and invest the resulting money in another venture. But this investment approach doesn’t take into account where those other ventures might come from or whether they are in any way diminished by the elimination of the first resource. How might the loss of tuna affect the ecosystem and other populations? Will there always be another fish population to harvest?

discounting future value

Giving more weight to short-term benefits and costs than to long-term ones.

What about consumers? We can all decrease our impact by making more sustainable choices and by consuming less. This doesn’t necessarily mean “doing without,” but it does mean being mindful of our choices and opting for sustainable or low-impact choices whenever possible. However, this requires transparency from the industries that produce and sell us goods and services. That is hard to come by with current business models, often because the businesses themselves don’t know all the external costs associated with their products. In order for its new plan to be successful, Interface was counting on its customers to make more sustainable choices as well. And make them they did. ReEntry 2.0 drew many new customers to Interface, including the Georgia state legislature, which purchased 13,000 yards of new carpets.

110

111