10.3 Populations need genetic diversity to evolve.

The ability of a population to adapt is a reflection of its tolerance limits, which largely depend on genetic diversity—different individuals having different versions of genes (called alleles). A population that is highly diverse (has individuals with many different traits) is likely to have wider tolerance limits, which increases the population’s potential to adapt to changes. This means it is more likely that some individuals will exist that can withstand (or even thrive in) the changes, and that the population as a whole will survive. If a change occurs that produces a condition outside of the range where individuals can survive and reproduce (for instance, the climate becomes too warm, or too dry), the population will die out. Similarly, if a new challenge is presented, such as the introduction of a new predator or competitor, the survival of the population will depend on whether there are any individuals in the population who can effectively deal with the new species. If the snakes on Guam were indeed responsible for killing off the birds, any birds that happened to have effective snake-avoidance behaviours would have had a greater chance of survival.

There are two main sources of variation that can increase genetic diversity in a population. The ultimate source of new variability is genetic mutation, a change in the DNA sequence in the sex cells that alters a gene, sometimes to the extent that it produces a new protein, and possibly a new trait. Mutations are rare, but because DNA replication and repair occurs all the time, rare events do happen. When a mutation produces traits that are beneficial, they can quickly be passed on to the next generation, allowing the population to evolve to be better adapted to its environment. A second source of genetic variety occurs as eggs and sperm are made: genetic recombination shuffles alleles around and sometimes produces individuals with new traits when a sperm fertilizes an egg.

171

172

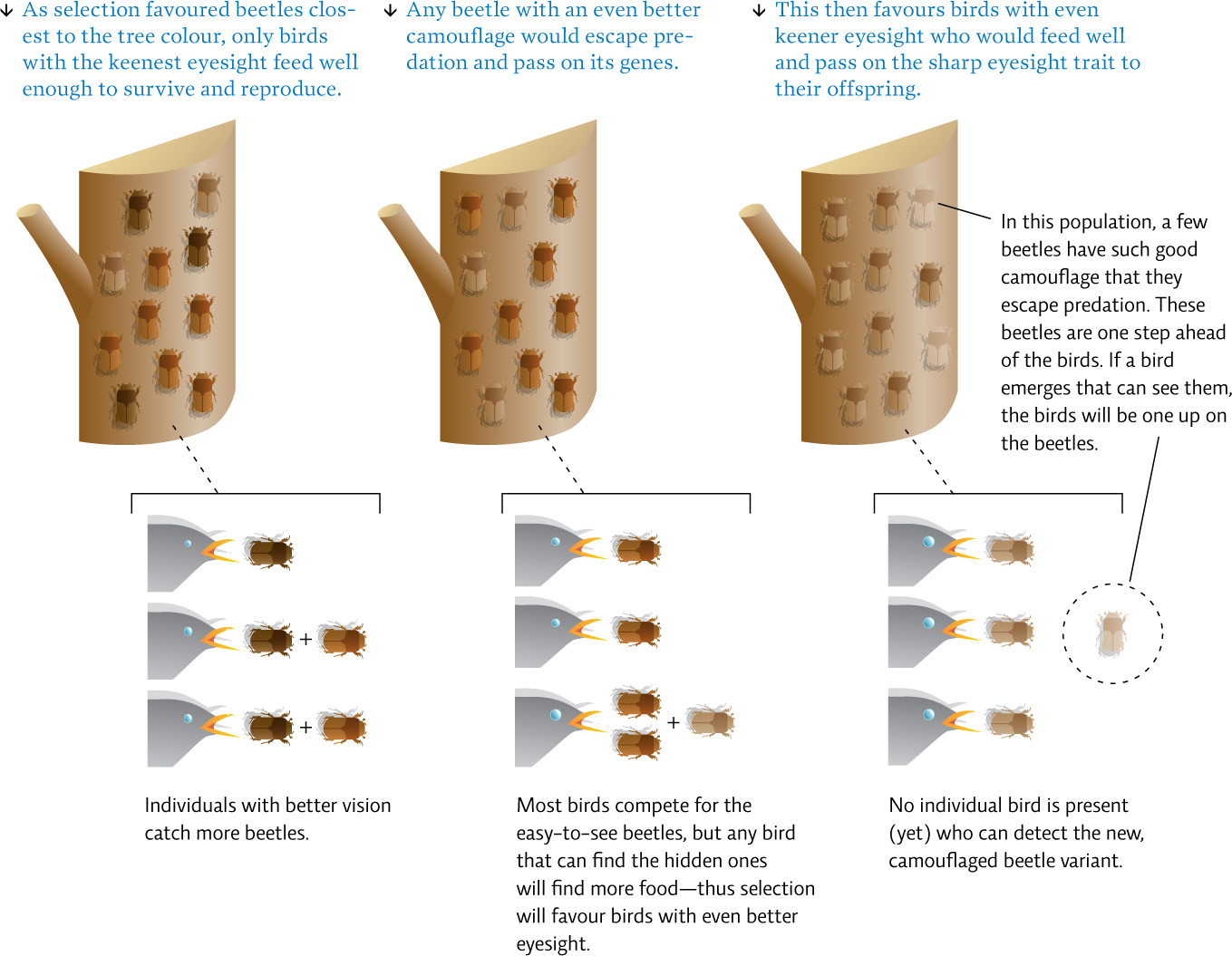

In coevolution, two species each provide the selective pressure that determines which of the other’s traits is favoured by natural selection. Predator and prey species usually evolve together, each exerting selective pressures that shape the other. As predators get better at catching prey, the only prey to survive are those a little better at escaping, and it is these individuals that reproduce and populate the next generation. This game of one-upmanship continues generation after generation, with each species affecting the differential survival and reproductive success of the other. The result can be a predator extremely well-equipped to capture prey, and prey extremely well-equipped to escape. [infographic 10.2]

If the birds on Guam were indeed eradicated by the invasive snake species, it was because the speed at which the eradication happened prevented the bird populations from potentially coevolving survival strategies to deal with the new snake population. The brown tree snake was already well adapted to prey upon birds. But Guam’s bird populations had never faced such a predator and had no natural defenses. It was an unfair fight. In fact, that the birds on Guam disappeared so quickly made it difficult to tease out the cause of their extinction at all. Savidge had to work backwards to solve the mystery, putting the missing pieces together, experiment by experiment. Her first step was to compare whether the distribution of the snakes on Guam matched up with the areas where birds had disappeared.

173

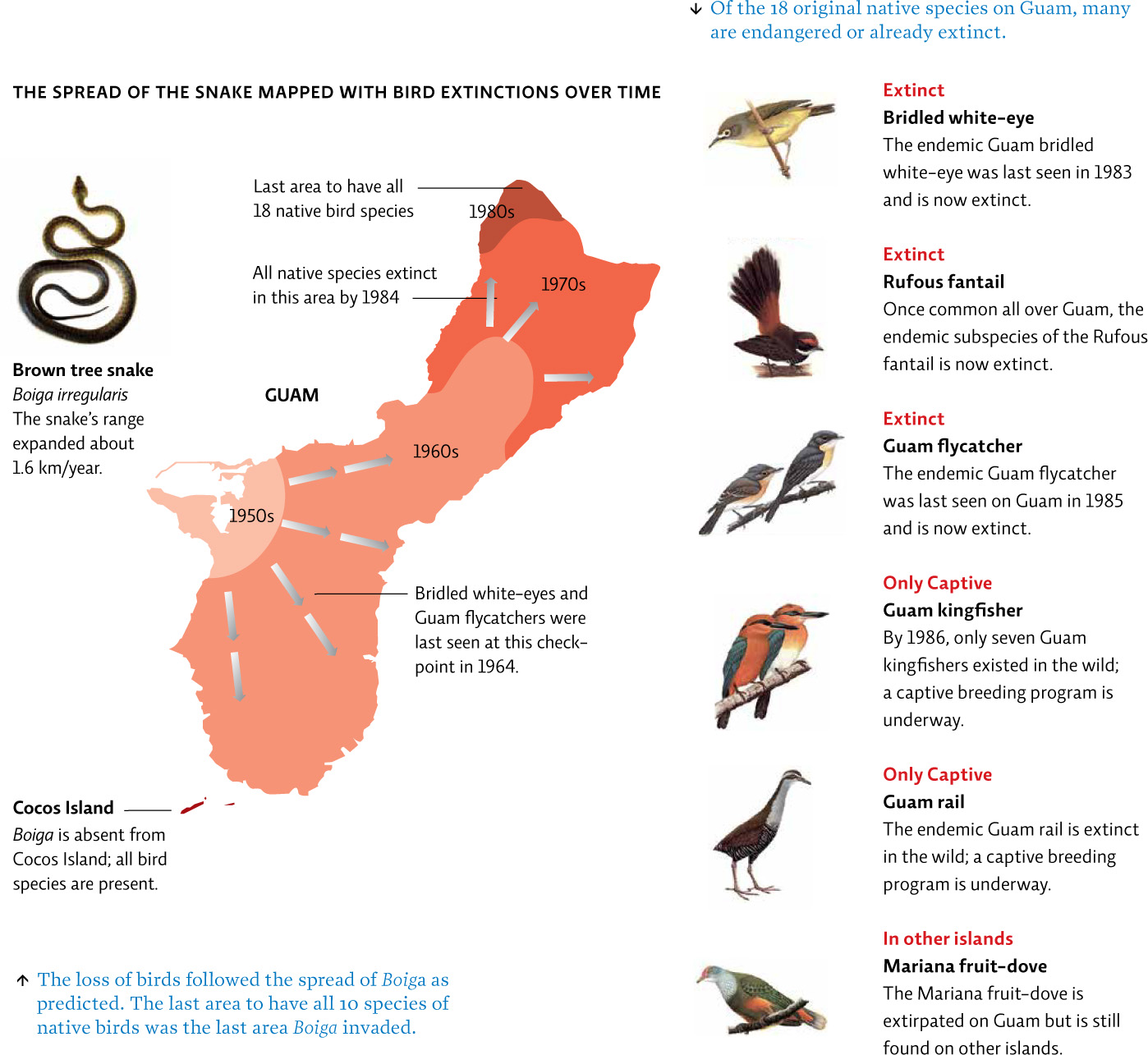

Based on what the residents told her, and what historical records like newspaper clippings reported, Savidge found that birds had begun to disappear first from southern Guam, and that their disappearances matched up perfectly with when the brown tree snakes had begun populating the area. Ritidian, an area on the very northernmost tip of Guam, on the other hand, was the last area to have lost its birds, and it was also the last to be colonized by the snakes. “I found a close correlation between the bird decline and the expansion of brown tree snakes around the island,” she says, which suggested to her that brown tree snakes really might be the culprit. [infographic 10.3]

Some of Guam’s bird species went extinct sooner than others. For instance, the endemic bridled white-eye, the gregarious bird species that was extinguished first, happens to be very small, raising the possibility that the small size of these birds might have put them at a disadvantage. Larger species like flycatchers survived longer, though they, too, eventually disappeared. Other bird species experienced extirpation; the Guam rail, for instance, is gone from Guam but other populations still live on the nearby island of Rota.

174