10.6 Extinction is normal, but the rate at which it is currently occurring appears to be increasing.

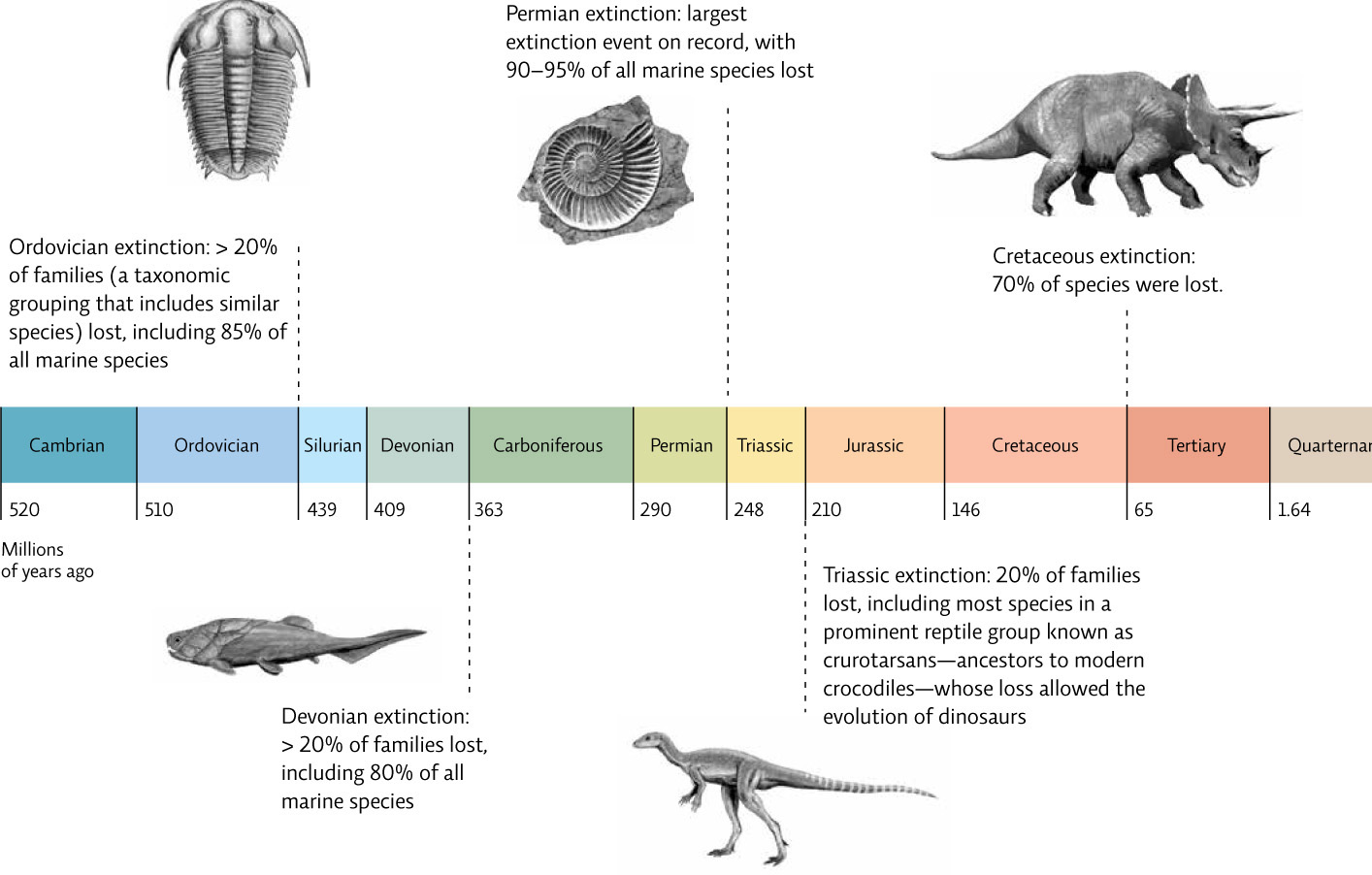

Extinction is nothing new on Earth. It is as constant and as common as evolution; by most estimates, more than 99% of all species that ever lived on the planet have gone extinct. Based on a critical analysis of the fossil record, scientists agree that there have been five major extinction events—when species went extinct at much greater rates than during intervening times, each event leading to the loss of 50% or more of the species present on Earth. The most infamous of these was the K-T boundary mass extinction, which occurred at the transition from the Cretaceous to the Tertiary period, 65 million years ago. Most scientists agree the K-T extinction event was set off by an asteroid impact in the Gulf of Mexico; 70% of all living species, including the dinosaurs, were wiped out.[infographic 10.5]

But these kinds of events often lead to the emergence of new species, as other populations adapt to the open niches that are left. Cycles of extinction and evolution ultimately gave rise to the diversity of life we see on Earth today—estimates range from 3 to 100 million species. Throughout most of time, the background rate of extinction—the average rate of extinction that occurs between mass extinction events—has been slow. The fossil record tells us that, on average, 1 species out of every million species goes extinct each year. In a world with 3 million species, this would be 3 species per year; if Earth is home to 100 million species, that would be 100 species per year.

Today, most scientists in this field agree that swelling human populations have triggered a sixth major extinction event, one that we are witnessing right now. Plant and animal extinction rates are currently greater than the background rate of extinction. For example, British researchers Ian Owens of the Imperial College of London and Peter Bennett of the University of Kent analyzed the extinction risk for 1012 threatened bird species and found that habitat destruction was cited as a risk factor in 70% of the cases, and other human interventions, such as the introduction of non-native species or overharvesting were implicated in 35% of the cases. In some areas with high endemic species diversity, such as a tropical rain forest, the rate can be quite high: one estimate puts it as high as 27 000 extinctions per year in tropical rain forests that are being cut down. A look at the historic mammalian fossil record reveals that, on average, 1 mammal species has become extinct every 200 years, but in the last 400 years we’ve documented 89 mammalian species extinctions—that is almost 45 times faster than the background rate.

178

Estimates of just how rapidly we are losing species vary, in part because we don’t know how many species exist and because it is hard to verify that a species actually is extinct. In an often-cited 1995 article published in the journal Science, researchers estimated that current rates of extinction range from 100 to 1000 times greater than background rates. If all species currently threatened become extinct, this would raise the high-end estimate to 10 000 times greater. A recent report in Nature suggests that current methods overestimate extinction rates by as much as 160% but points out that even the low-end estimates are a cause for concern. And while scientists debate whether species extinctions are 100 times or 1000 times faster than normal worldwide, it may be more useful to evaluate threats at a local level, like in Guam, and focus efforts on reducing species loss there. Especially on a small, isolated island, a rate that is even 10 times higher than normal is significant.

What we do know is that today’s accelerated extinction is largely driven by human actions. As the human population increases, our impact is becoming much more devastating for other species. We remove the resources they need to survive, minimize their habitat ranges, introduce new predators or competitors, and strip them of their genetic diversity, all of which slowly eliminate them. In Guam, the near-total disappearance of birds between the 1960s and 1980s was a biological murder mystery of astounding proportions—one that illustrates just how vulnerable populations are to sudden changes.