10.7 Biodiversity is threatened worldwide.

The world’s biodiversity faces threats on several fronts. If a species faces a very high risk of extinction in the immediate future, scientists classify that species as endangered. When a species is likely to become endangered in the near future, they say it is threatened. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) classifies a species as endangered when it suffers a population loss of 80% or greater in a 3-year period. In Canada, a species is classified as threatened or endangered based on a qualitative assessment of several factors, including the state of its natural habitat, the threat it faces from disease or predation, and the degree to which it is being overutilized for commercial, recreational, or scientific purposes.

Globally, the IUCN estimates that 40% of all known species face extinction. Recent studies indicate that there are only about 3200 tigers, 720 mountain gorillas, and 60 Javan rhinoceros left in the wild. Once the last members of those species die, the species will be lost forever. But the fight for survival is not confined to large, furry mammals. In fact, the majority of listed endangered species are plants, not animals, and this could impact us directly. Of the 70 000 or so flowering and nonflowering plants with known medicinal value, more than 15 000 are endangered (see Chapter 9).

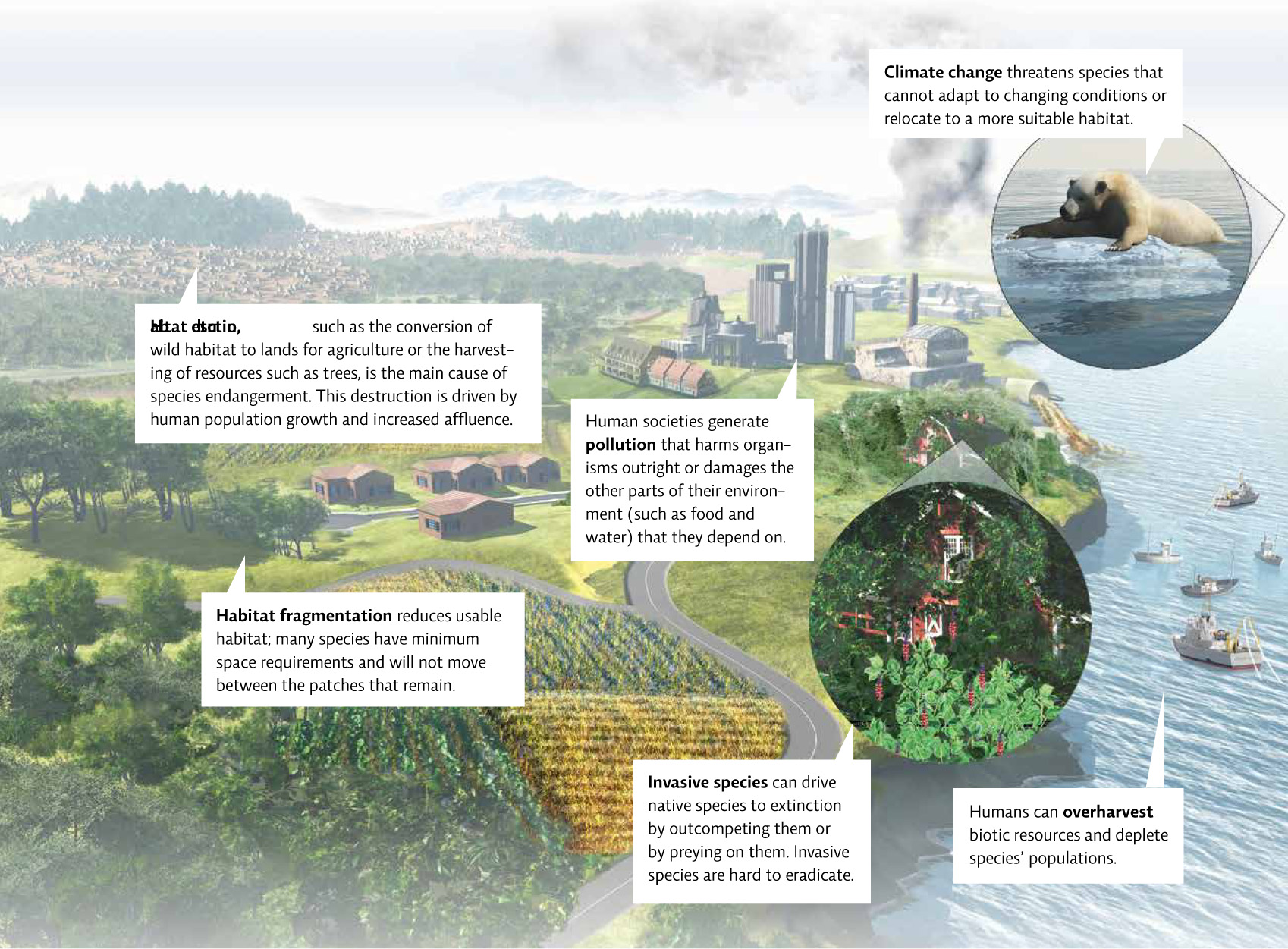

Scientific consensus is that human-caused threats are the main reason for the high extinction rates of recent decades. In addition to the introduction of invasive species, these threats include habitat destruction, pollution, overharvesting, and anthropogenic climate change. Many of these threats are related to overpopulation and affluence that leads to greater resource use. [infographic 10.6]

179

Human activity alters the face of landscapes and the sea floor in ways that critically damage habitats needed by species for their survival. Habitat destruction, whether it be the physical destruction of an ecosystem (e.g., deforestation) or the degradation of a system such that the system is no longer inhabitable (e.g., pollution), is the number one cause of species endangerment. For some species, habitat fragmentation can be as devastating as total habitat destruction. For instance, a road that cuts through a forest could reduce usable habitat by half for a core species that will not venture close to the edge, let alone cross the open space. Isolated populations in fragmented habitats inbreed and lose genetic diversity, becoming even more vulnerable to further environmental perturbations. Edge species that live at the juncture of two different habitats (such as where a forest meets a field) may actually benefit from habitat fragmentation as the amount of “edge” increases, but only as long as suitable amounts of overall habitat remain. Corridors or connections between fragmented habitats are only useful for core species if the corridor is wide enough to offer protection from the edge habitat; otherwise, core species will not use the corridor. (See Chapter 8 for other examples of edge and core effects.)