11.1 Repairing a forest ecosystem one tree at a time

| CHAPTER 11 | FORESTS |

RETURNING TREES TO HAITI

184

185

CORE MESSAGE

Forests have great economic value but we must balance that with the value of their ecosystem services and sociocultural benefits. Sustainable management practices allow us to harvest forest products without destroying the forest or its ability to provide ecosystem services and future products.

GUIDING QUESTIONS

After reading this chapter, you should be able to answer the following questions:

In general what are the characteristics of a forest biome? What are the three main types of forests and what influences which forest type is found in a given area?

In general what are the characteristics of a forest biome? What are the three main types of forests and what influences which forest type is found in a given area? What is the three-dimensional structure of a forest and how are the plant species found there adapted to their level of the forest?

What is the three-dimensional structure of a forest and how are the plant species found there adapted to their level of the forest? What ecosystem services do forests provide? Why might it be useful to put a dollar value on these services?

What ecosystem services do forests provide? Why might it be useful to put a dollar value on these services? What is the current state worldwide of forest resources? What threats exist?

What is the current state worldwide of forest resources? What threats exist? What are ways that we can act to protect and sustainably manage forest resources? What trade-offs exist with our choices?

What are ways that we can act to protect and sustainably manage forest resources? What trade-offs exist with our choices?

186

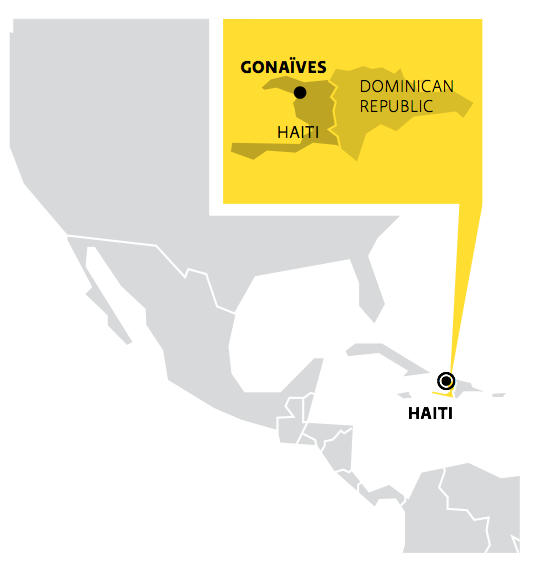

When Jean Robert was a young boy, the mountains surrounding the Haitian city of Gonaïves (pronounced go-nah-eev) were still lush and green with trees. His family’s hillside farm—small though it was—provided a steady crop of mangoes and avocados in the summer, coffee and cassava in the fall, and wood for charcoal throughout the year. But today, the forests are gone and the mountains are bare. Not only have crop yields shrunk—from enough to sell in the local markets, to barely enough to feed a family—but the mountain homes and the city below have been left defenceless against the onslaught of tropical storms that pound Haiti every summer. Unencumbered by trunks or roots or shrubs, water rushes freely downward, gathering into apocalyptic mudslides that destroy homes, crops, and livelihoods. In 2004, a single storm claimed more than 2000 lives from this one city.

Now, instead of growing mangoes and cassava, Robert and his neighbours are trying to grow trees. Working as a team, moving in slow, deliberate, farm-by-farm patterns across the mountainside, the community work group, or kombit, plants a carefully planned mix of fruit and timber trees. By the end of the month, they say, each member will have his or her own saplings to tend to. If the saplings survive, and if the American ecologists they’ve been consulting with are right, their efforts will give rise to a new era of sustainable forestry, which strikes a balance between what people need from the forest and what the forest itself needs to survive.

WHERE ARE HAITI AND GONAÏVES?

It’s a scene being replayed all over Haiti. When Europeans first arrived in the country some 500 years ago, two-thirds of the land was covered in forests so majestic that explorers dubbed this region “the Pearl of the Antilles.” But as the centuries passed, the forests were cleared—sometimes with amazing breadth, to make way for coffee and sugar plantations; other times, in discrete chunks that Haitian peasants would then convert into subsistence farms. Many of the trees—along with the coffee and sugar crops that displaced them—were sold overseas. Most of the rest provided fuel for heating Haitian homes and cooking Haitian meals.

Today, less than 2% of that original forest remains; 6% of the land has no soil left at all. In these places, dead tree stumps, bleached white by the sun, protrude from the ground like bones poking through decayed flesh. And Haiti has become both the poorest and the most environmentally degraded country in the Western Hemisphere. With few trees and little soil, drinking water has grown polluted, crops have dwindled, and the people have suffered.

Farmers like Jean Robert say that forests are the key to changing all of that. They have planted thousands of trees in these mountains in recent years, and hope to plant thousands more. “Almost all of the country’s problems—natural disasters, food shortages, poverty—can be traced back to rampant deforestation,” says Haitian ecologist Timote Georges, who is working with the American non-profit Trees for the Future to reforest the mountains around Gonaïves. “So if we want to fix the country, we have to put the forests back and then find a way to manage them better.”

187

That’s no small feat. Forests, after all, are one of our most contentious resources. Such is the range of economic benefits and ecosystem services they provide that any one use must be weighed against a host of others, and immediate human needs are frequently pitted against long-term conservation goals. In Haiti, where most people live on less than $2 a day, trees provide food, energy, building material, and desperately needed income. To stop them from being chopped down, Georges and his fellow Haitians will have to find alternative sources of each, not to mention a farming method that doesn’t require clearing the forests.

But to really understand how trees might help alleviate poverty, we must first consider just what forests are, what they do for us, and why so many of them are being chopped down in the first place.