11.2 The location and characteristics of forest biomes are influenced by temperature and precipitation.

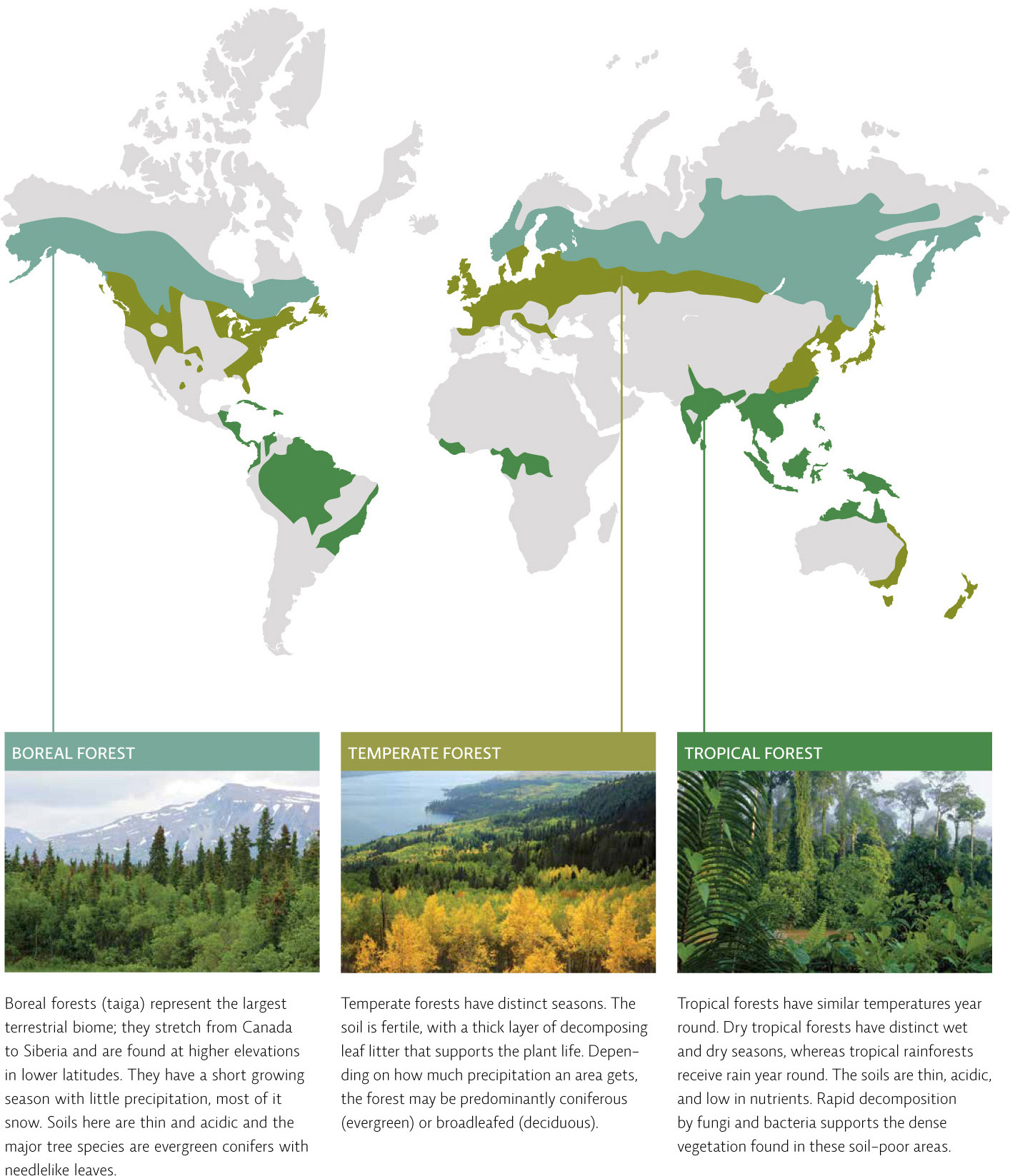

Forests are biomes dominated by trees. They currently cover about 30% of the planet’s landmass but, thanks to their sheer concentration of biodiversity, are home to more than 50% of Earth’s terrestrial life and more than 60% of its green, photosynthesizing leaves. There are many types of forest biomes around the globe, each determined by the temperature and amount of precipitation the area receives. Boreal forests, characterized by evergreen species like spruce and fir, cover vast tracts of land in the higher latitudes and altitudes and are characterized by low temperatures and precipitation levels; they represent some of the last expansive forests left on Earth. Temperate forests, which contain deciduous trees that lose their leaves in winter, like oak, hickory, and maple, are found in the wet areas of mid-latitudes. These forests are not as expansive as the boreal forests because they are found in latitudes with high human populations. In Canada, the world’s largest timber exporter, 45% of our land area is forested, but we have lost 6% of original forest cover, mostly from temperate forest areas. Tropical forests contain a diverse mix of tree and undergrowth species and are found in tropical latitudes where temperatures do not vary much throughout the year. [infographic 11.1]

188

189

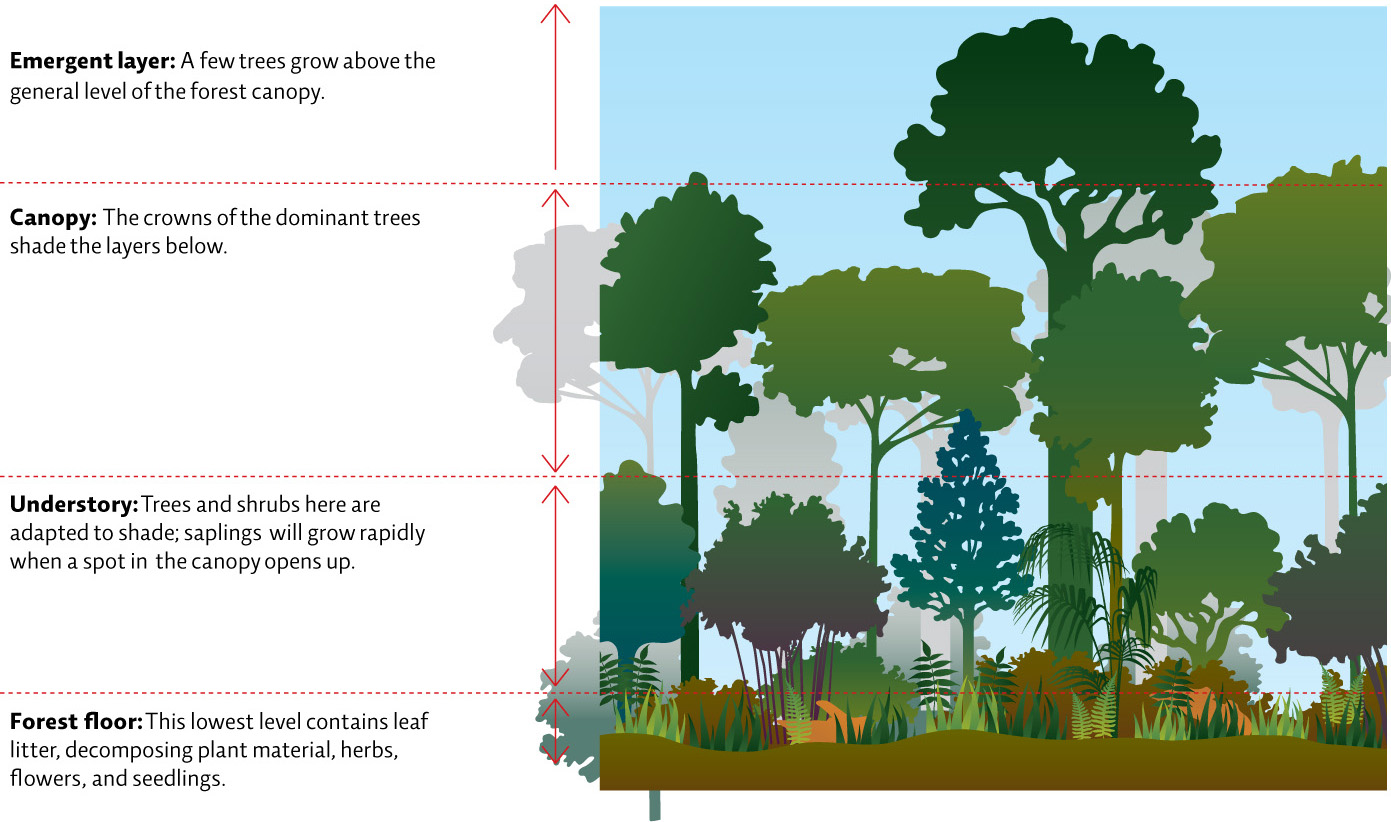

Most forests consist of four distinct layers. The canopy, formed by the overlapping crowns of the tallest trees, makes up the ceiling of the forest. Some even taller trees may reach above the canopy to form an emergent layer. Beneath the canopy is the understory layer, where shade-tolerant shrubs, smaller trees, or the saplings of larger trees grow. Sometimes these trees are dense enough to form a lower canopy. The lowest level is the forest floor, which is typically made up of seedlings, herbs, wildflowers, and ferns. The forest floor also contains soil, which is composed of leaf litter and other debris—branches, logs, and stumps—that decomposes over time.

190

Within each forest layer is a range of species uniquely suited to the temperature, humidity, and amount of sunlight that layer receives, and well-adapted to its particular neighbours. For instance, in a temperate deciduous forest, wildflowers on the forest floor will bloom early in the spring before the bigger trees “leaf out” and block the sun. Sunlight is a precious commodity on the forest floor and wildflowers compete for it. One wildflower species may bloom one week and another the next week. Disruption to one part of the forest (for instance, cutting down a tree that opens the canopy) can have a trickle-down effect that impacts each subsequent layer. [infographic 11.2]

Most experts agree that the biggest modern contributors to Haitian deforestation are the food and fuel needs of Haitians themselves. But throughout the nation’s history, there were many other culprits—from 18th-century French colonizers’ coffee and sugar plantations, to the timber industry of the 19th and 20th centuries. As the population grew—from 3 million in 1940 to 9 million in 2000—rural Haitians were forced to clear ever-larger areas of mountainside to make room for subsistence crops. The trees themselves doubled as a source of fuel and cash for families who not only used the wood to cook with but also sold it as charcoal in Port-Au-Prince, the nation’s densely populated, energy-starved capital city.

Charcoal—partially burned wood that ignites more easily and burns hotter than the original wood itself—is used in many developing countries that lack other reliable fuel sources. Charcoal is produced in a variety of ways but all include a slow, low-temperature “roasting” of the wood in a low-oxygen environment. This process releases both CO2 and particulates (soot) into the atmosphere. Like Haiti, other areas dependent on charcoal as their major fuel have become severely deforested and plagued with air pollution. Many African nations including Mozambique, Malawi, Somalia, and Tanzania are experiencing rampant deforestation largely to provide charcoal and fuel wood. In Mozambique, for example, charcoal is the main fuel for 80% of the population. More than 2.5 million trees are cut each year in Somalia—that is 10 trees per household, per month.

191

In time, Haiti’s charcoal trade grew to account for 20% of the rural economy and 80% of the country’s energy supply. Before long, 98% of the country’s forests had been chopped down and Haitians were burning 30 million trees’ worth of charcoal annually. “The trade itself became this incredibly destructive force,” says Andrew Morton, a forest ecologist for the United Nations Environment Programme. “And the fact that it was based not on foreigners exploiting the land for profit, but on poor Haitians trying to earn money and feed their families and heat their homes, made it impossible to stop. There really was no other source of energy.”

Of course, charcoal wasn’t the only crucial service the trees provided.