11.3 Forests provide a range of goods and services and face a number of threats.

Though trees are the largest and most notable life-forms present, a forest is much more than just its trees. Together, the species inhabiting the different layers participate in a delicate symphony of chemical and physical cycles that produce an invaluable range of ecosystem services for the planet.

It starts with the soil, which the forest itself helps to form and maintain: leaves and branches die, fall to the ground, and decay, forming a thick brown layer of nutrients in which all future generations of plant life will take root.

While dead and decaying plants help form the soil, living ones hold it in place. During rain storms, soil anchored in by roots, especially by tree roots, can’t flow as easily down hillsides into nearby surface waters (lakes, streams, oceans), where it would contaminate them with sediment and chemicals it picked up from the ground’s surface. By slowing this flow of rainwater across the ground’s surface (called stormwater runoff), a well-vegetated area allows more water to soak into the ground, recharging the groundwater supplies that provide area residents with their major source of drinking water. The soil also traps chemicals that might otherwise contaminate that drinking water. (See Chapter 16 for more on runoff.)

192

While plants, soil, and water are playing off one another in this manner, the forest is also conducting another important cycle: pulling carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and replacing it with oxygen. In fact, forests as a whole store more carbon in their biomass, litter, and soil than all the carbon in the atmosphere, making this biome one of the world’s largest carbon sinks (an area that stores more carbon than it releases, such as the standing timber in a forest or organic matter in soil). And forest leaves produce so much oxygen that they are commonly referred to as “the lungs of the planet.”

Last but not least, virtually every layer of forest provides food and habitat for a bevy of animals (vertebrates and invertebrates), plants, fungi, and microbes; these creatures all do their part to contribute to the functioning of the forest ecosystem as a whole. It is difficult to overstate the importance of forests to the biosphere.

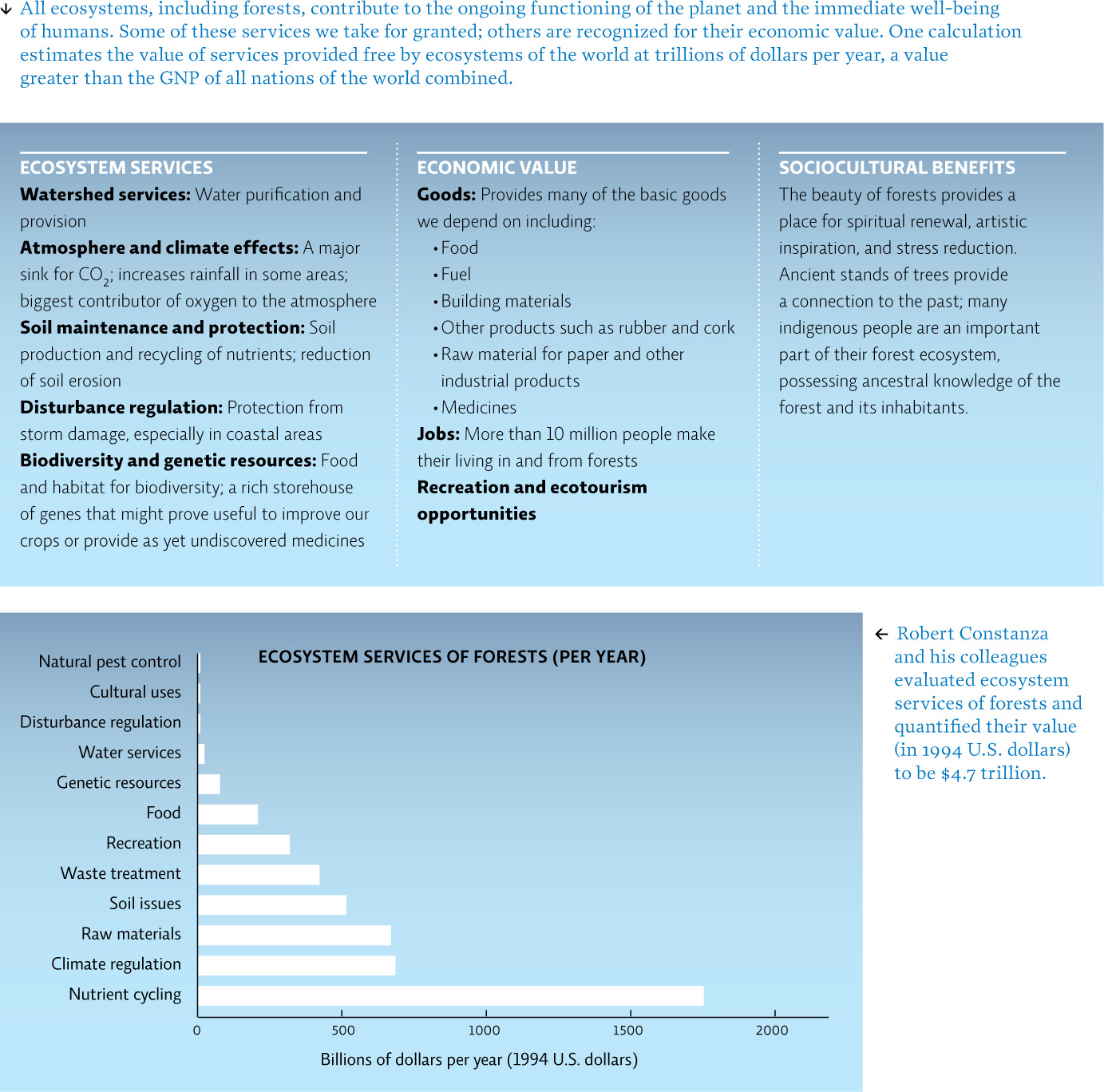

In addition to all these ecosystem services, forests also provide a range of economic benefits. In fact, humans have relied on forests for millennia for a multitude of consumer goods. Wood products, including lumber, firewood, charcoal, paper pulp, and some medicines, account for some $100 billion in global trade every year. On top of that, the wildlife supported by forests provides humans with food and recreational hunting opportunities, both of which have economic value. [infographic 11.3]

193

In Haiti, the cost of deforestation spun out over decades and proved catastrophic. Soil eroded down into streams, rivers, and gullies, clogging them with sediment and disrupting aquatic ecosystems. With nothing to absorb the water, floods became more severe and groundwater sources were quickly depleted as the water flowed away rather than soaking into the ground. Slowly, crop yields shrank. As the forest habitat was fragmented, biodiversity dwindled. And as the trees vanished, the people of Haiti suffered. Unlike wealthier countries they could not afford expensive water purification systems–a service the forests once provided for free. “It took some years before we could feel the other effects of deforestation,” says Georges. “The floods got worse and we lost drinking water to runoff and pollution. And once those problems started, there was no easy way to fix them.”

194

195

Eventually, everyone who could abandoned the countryside for the capital city. Even that did not stop the tide of deforestation. As the population swelled, so did the demand for fuel, which in Haiti, still comes almost exclusively from trees.

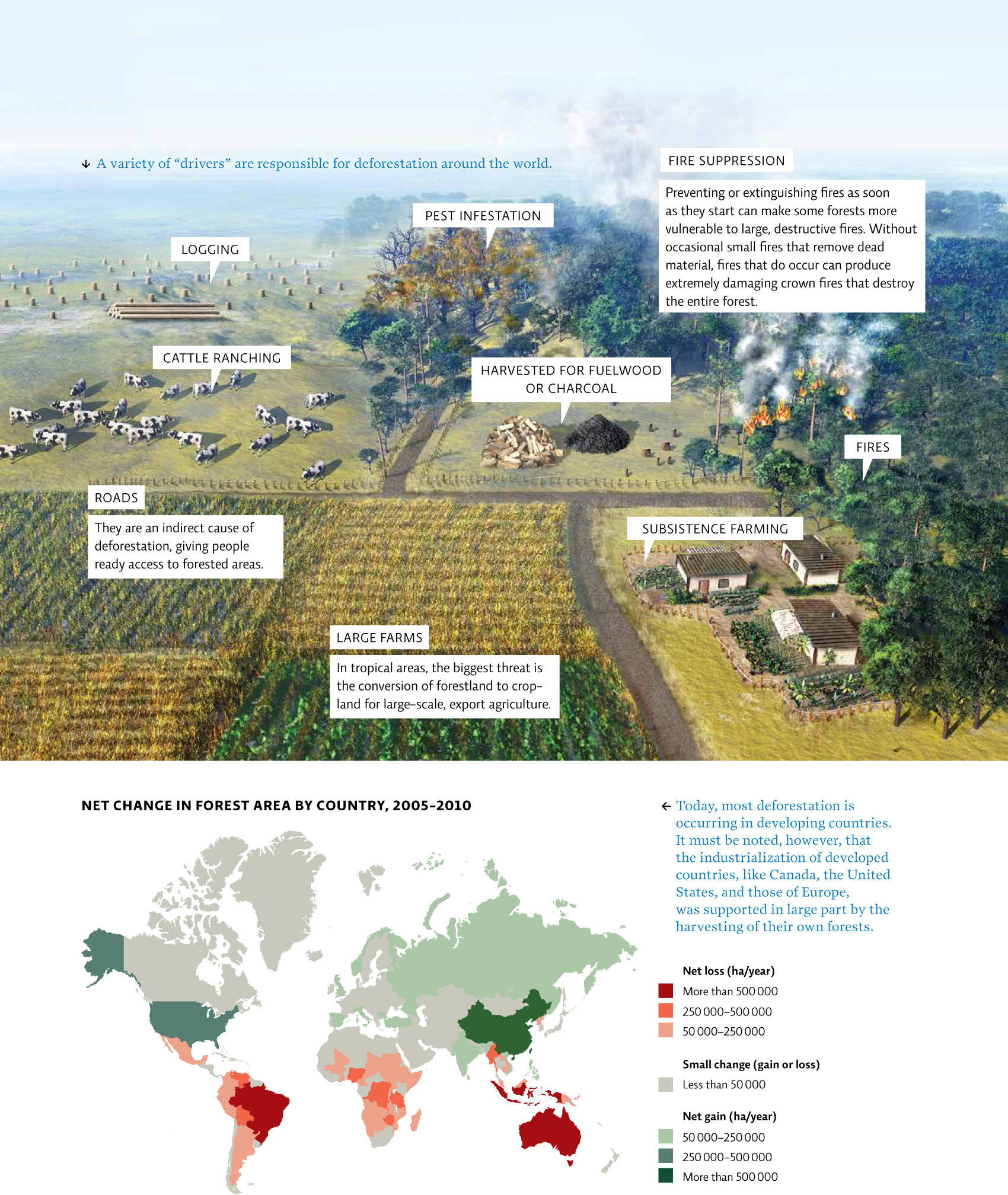

Today global deforestation has slowed considerably, from 9 million hectares (ha) per year in the 1990s down to 5.2 million ha in the year 2000, but the planet still has a net loss of forested land every year. There are three main culprits behind this trend: the harvesting of forests for wood and wood products, the conversion of forests into agricultural land, and urbanization. Management of fire is also a factor in forest destruction. Frequent fires remove deadwood and other flammable material but if we suppress these fires, the deadwood builds up so that when a fire does come through, it can burn so hot it catches the entire forest on fire. It turns out that fire is actually needed to maintain some forests whose trees are fire-adapted with seeds that only germinate when exposed to the heat of a fire. The nature and degree of each of these threats varies by country because forests are often used and managed differently in developing countries than they are in developed ones. [infographic 11.4]

“The floods got worse and we lost drinking water to runoff and pollution. And once those problems started, there was no easy way to fix them.”—Timote Georges

In general, deforestation occurs at a greater rate in developing countries like Haiti, where dire poverty and a lack of alternatives force people to harvest their forests or remove them for other land uses. They need wood and charcoal for fuel and housing; they need more space for agriculture; and they need commodities to sell in the marketplace. In most cases, developing countries also have far greater remaining forest stands than developed countries, but many of these stands are falling fast.

In fact, many if not most developed countries, including Canada, the United States, and most European countries, became developed in part by harvesting their own forests. Today, European countries have fewer forest stands than many developing countries, but they also have much more stringent regulations in place to protect those that are left. These regulations—and the ability to enforce them—help keep deforestation in check.