11.4 Forests can be managed to protect or enhance their ecological and economic productivity.

In Canada, 7% of forests are privately owned, and 93% publicly owned. Provincial/territorial governments manage 83% of public forests, while the federal government has management jurisdiction over the other 17%. This means that forestry legislation is split over multiple levels of government, which leads to difficulties in regulating forestry practices nationally. It is also important to recognize that while almost 50% of Canada is forested, most of that area is highly inaccessible; most logging occurs near populated areas and on the west and east coasts. The most well-known logging operations in Canada are in British Columbia, where excessive clear-cutting in mountainous areas has led to large economic gains, but also to ecosystem loss and degradation. This has reduced the future economic potential for forestry, but also for the salmon industry due to excess sedimentation of spawning grounds.

Ecological knowledge can facilitate more effective forest management in developed nations. The Canadian Forest Service (CFS), a branch of Natural Resources Canada, is a science-based federal policy advisory body. Over the past century, Canada and the CFS have moved away from a timber-focused harvesting approach, towards ecosystem-based forest management. In 1992, Canada committed to “sustainable forest management” as part of a National Forest Strategy. This approach recognizes the non-timber values of forests, such as recreational uses and carbon storage, which is slowly moving forestry practices in Canada away from harvesting as much as is physically possible and economically profitable towards a maximum sustainable yield (MSY), harvesting as much as sustainably possible (but no more) for the greatest economic benefit.

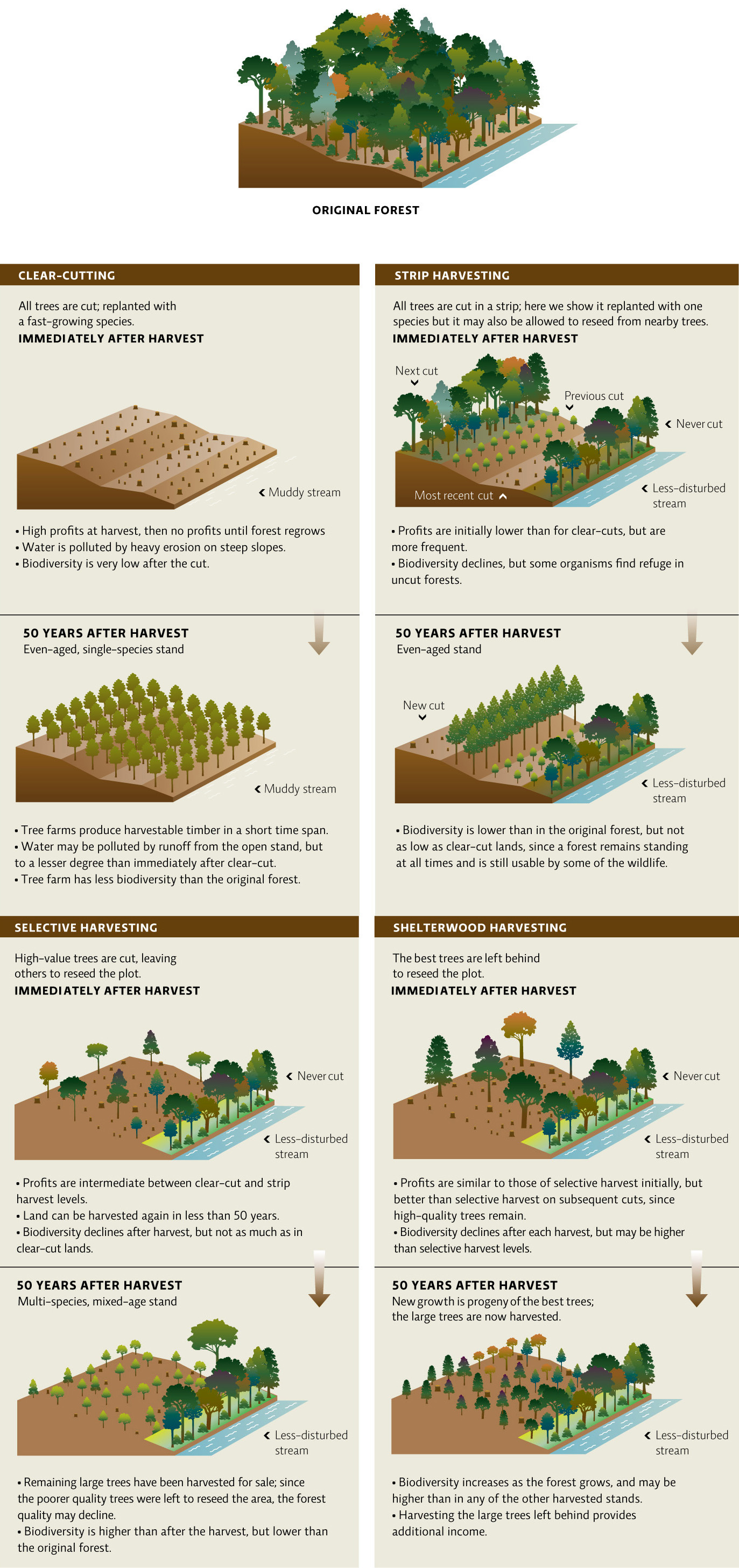

Though some timber harvesting methods are very damaging to the integrity of the forest (such as large clear-cuts on steep slopes), methods are available that reduce disruption to the ecosystem while still providing economically valuable forest products. Ideally, the stand of trees—its health, age, and species composition—and the slope of the land determine the harvesting method. Consideration is also given to the other species that reside there. When trees are harvested properly, they can provide immediate and long-term economic benefits without serious environmental damage. Even clear-cutting can be appropriate when it increases the overall health and viability of a future forest by removing unhealthy or genetically inferior trees and replacing them with better stock. Clear-cuts followed by planting of a fast-growing, high-value tree (a tree farm) can also reduce the pressure to cut other forests (though there must be enough native forests left in areas suitable for tree farms to avoid serious ecological damage due to biodiversity loss). [INFOGRAPHIC 11.5]

196

197

Forest management is not without its critics, however. Conflicting interests make it difficult to achieve a balance between multiple forest uses and ecosystem protection. For example, harvesting trees in British Columbia provides many jobs, good profits for timber companies, and useful products for our homes and businesses, but can reduce biodiversity and harm salmon runs, which are vital for ecosystem health, native cultures, and the tourism industry.

Debates are often oversimplified and shown as two competing options—owls versus jobs—however, a more accurate cost-accounting of potential forest uses requires that we factor in the economic and ecological value of ecosystem services. Forests are so important economically, ecologically, recreationally, and even spiritually that no matter how well managed they are, they will always be a contentious resource.

198

Of course, any gains made by developed countries are still largely offset by deforestation in countries like Haiti. For example, deforestation in Mexico has largely offset new plantings and reforestation in the United States and Canada. Central America has lost more than 5 million ha since 1990 and Europe has gained 12 million ha. “Industrial countries may be leading the way in conserving their own forests,” says Morton. “But their demand for wood drives much of the deforestation elsewhere.” Multinational corporations have simply moved deforestation operations to developing nations where regulation and enforcement are often lacking and people are desperate for income. They then export products to wealthier countries for sale.

Three months after the kombit visited his hillside farm, Jean Robert is harvesting Moringa leaves. They’re tasty, packed with protein, and when harvested properly they regrow rather quickly. If everything goes as expected, he will eventually have a bevy of crops to see him through the year: mangoes in the summertime, coffee in the fall, and if he’s lucky, oak and mahogany stands that will yield high prices in the timber market down the road. In the meantime, the Moringa trees provide his family with a sustainable supply of protein and fuel wood.

The trees Georges’ team plants can be broken down into three main types. They start with fast-growing, multipurpose trees like the Moringa. Because it is a nitrogen-fixing plant, the Moringa helps refertilize the soil. And because it grows quickly, it can provide a sustainable source of food and fuel wood. Next, they plant fruit trees—mangoes, avocados, and citrus. These trees take longer—3 to 5 years—before they are ready to harvest, but they put down roots and thus stabilize the soil in just a few months’ time. “Farmers are less likely to cut down fruit trees for charcoal, because they know it will provide the kind of food they can both eat and sell for profit,” says Georges. “Fruit trees are worth something alive.” The last thing the kombit will plant are the slow-growing timber trees, which may be sustainably and profitably harvested in the future, but don’t provide any immediate benefits to the farmers. “The goal is to mix it up,” says Georges. “You can create a whole stable system that’s going to provide money and food throughout the seasons and across the years.”

199

Of course, for any of this to work, urban-dwelling Haitians will need a new, sustainable energy source.