12.1 The key to recovering the world’s grasslands may be a surprising one

| CHAPTER 12 | GRASSLANDS |

RESTORING THE RANGE

204

205

CORE MESSAGE

Grasslands are a critical resource, offering many important ecosystem services as well as being used for grazing of livestock, growing crops, and even production of biomass for biofuel energy. Grasslands are found all over the world, but are currently endangered by overuse and a changing climate. “Desertification” caused by overgrazing is the most common problem facing grasslands, but innovative practices in managing livestock can help protect the world’s grasslands.

GUIDING QUESTIONS

After reading this chapter, you should be able to answer the following questions:

What is a grassland? What kinds of grasslands are there and where are they found?

What is a grassland? What kinds of grasslands are there and where are they found? Why are grasslands important?

Why are grasslands important? How do overgrazing and undergrazing affect grasslands?

How do overgrazing and undergrazing affect grasslands? What is involved in the formation of soil and how does land use affect it?

What is involved in the formation of soil and how does land use affect it? How can we manage grasslands to lessen the threats they face while still using them productively?

How can we manage grasslands to lessen the threats they face while still using them productively?

206

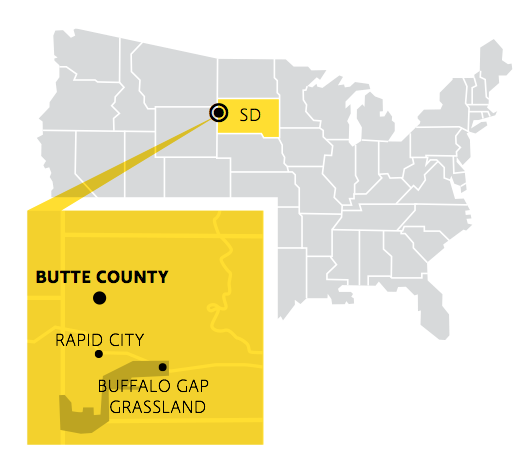

When Jim Howell, an ecologist and fifth-generation cattle rancher, first announced his plans to revive Horse Creek Ranch in Butte County, South Dakota, friends said he was either crazy or foolish. Sure, the ranch had once encompassed some of the best grazing land in the country, but persistent drought and too many cattle had long since brought those days of plenty to a close. Like so many ranches around it, Horse Creek’s pastures were too parched and degraded to sustain much of anything, let alone an entire herd of cattle.

Across the Great Plains, rangeland (land that humans use to graze livestock) is drying out and ranchers are growing desperate. In some places, the degradation is so bad that prairie grasslands are becoming deserts.

Normally this process, known as desertification, is both natural and slow. As climates shift over geologic time, grasslands morph into desert and deserts back into grassland in a cycle both never-ending and imperceptibly gradual. These days, it’s occurring much more rapidly than that—3 metres per year in West Texas alone. Part of the problem is climate change. But most experts agree that the biggest culprit, by far, is overgrazing—when too many animals feed on a given patch of land.

Desertification is not unique to the Great Plains. Around the world, from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe, 70% of the planet’s rangeland is threatened. This represents roughly one-third of the world’s entire land surface. And while the phenomenon has not garnered as much media attention as, say, global climate change, the consequences are no less dire. In fact, from the Fertile Crescent of ancient Babylon to modern-day developing countries like Darfur, desertification has been the stuff of wars. The cascade is both simple and devastatingly comprehensive: plants die, soil erodes, prairies fall to dust, famine sets in, economies falter, societies fail.

WHERE IS HORSE CREEK RANCH, SOUTH DAKOTA?

Since the early 1980s, the U.S. government has paid hundreds of thousands of ranchers to quit ranching so that vast swaths of degraded grassland can have a chance to recover. But critics say that holding the land in such conservation reserve programs decimates local prairie economies. “There are real environmental benefits to placing the land in trust and saying it can’t be grazed or farmed over anymore,” says Howell. “But it leaves farmers dependent on government cheques and does nothing to stimulate the local economy.”

Starting with Horse Creek—a forgotten ranch, in a fading prairie town—Howell and his business partners, who took control of the ranch in 2008, are working on a different solution, one that aims to repair economy and environment in tandem. The bottom line, they say, is this: if you want to save the prairies, you’ve got to graze more cattle, not less.