12.3 Grasslands face a variety of human and natural threats.

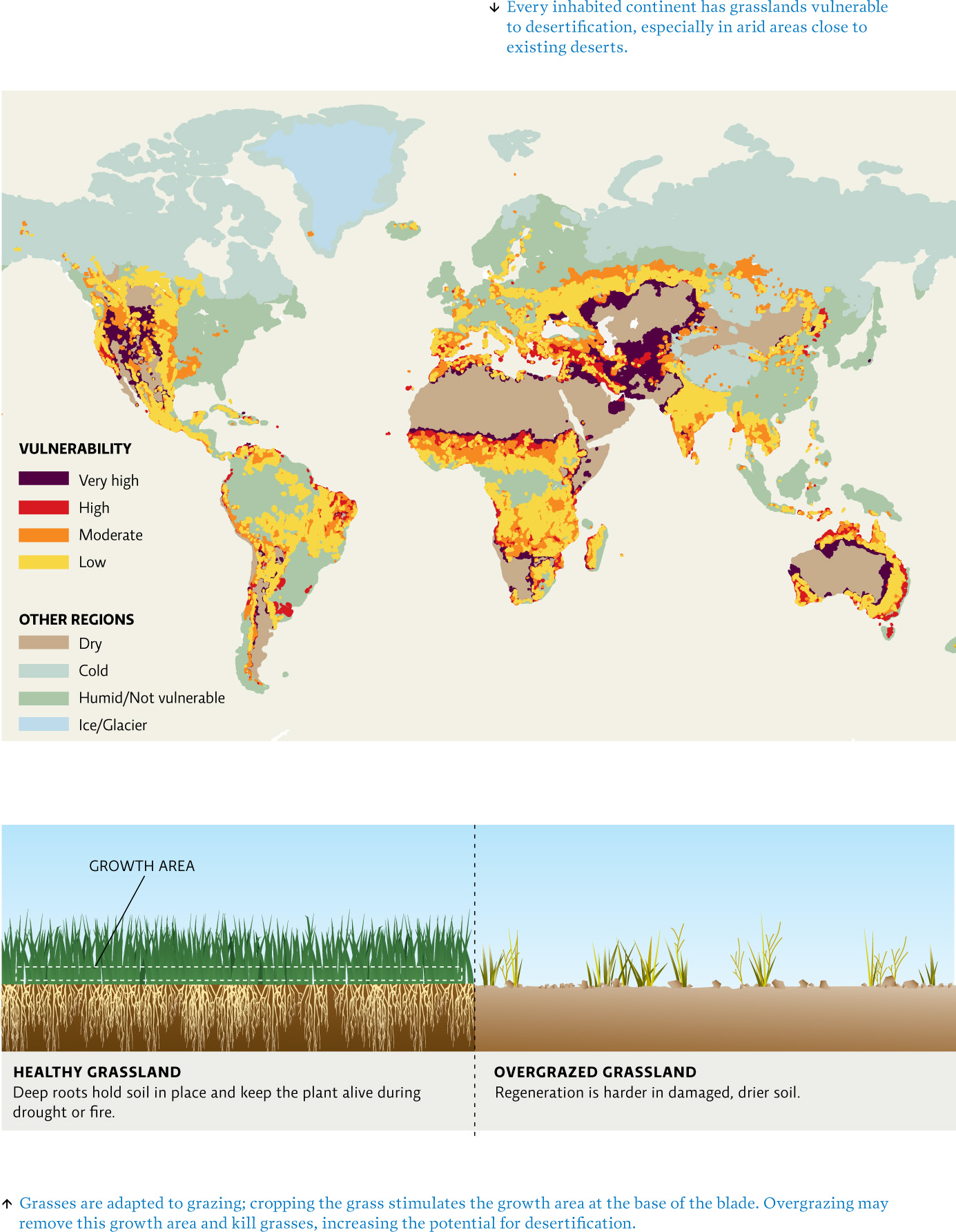

A trifecta of forces now threatens all of these goods and services. First, global climate change: as temperatures rise, scientists expect that shifting rainfall patterns will help push many current grasslands—including vast swaths of Canada’s prairies—into desert. The second threat involves human land-use decisions: rising global populations will force us to convert more land into cities and suburbs for living, and into croplands for food. Their wide, flat expanses and nutrient-rich soil make grasslands ideal for both. The third, and many say largest, threat that grasslands face is the one posed by overgrazing.

Ironically, grazing is normally very good for grasslands. Because wild herbivores evolved to subsist on grasslands alone, both grazers and grasses are well adapted to grazing. Grasses can grow from the base upward, so by clipping off the top part of the blade, herbivores expose new growth shoots to the sunlight, thus stimulating the plants’ growth. By breaking up the soil with their hooves, they allow water to penetrate the ground and enable seeds to germinate and take root. And as they defecate and urinate, large grazing mammals return nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus to the soil in a form that plants can easily absorb.

But when grass is overgrazed, or chewed down to its roots, the growth area on the blade is destroyed, the blade can no longer regenerate, and the plant eventually dies. When too many plants die at once, the soil has nothing to hold it in place. And when too many large grazing animals stomp their hooves directly onto the soil, the soil becomes compacted, which makes it harder for water to penetrate, seeds to germinate, or seedlings to grow. [infographic 12.3]

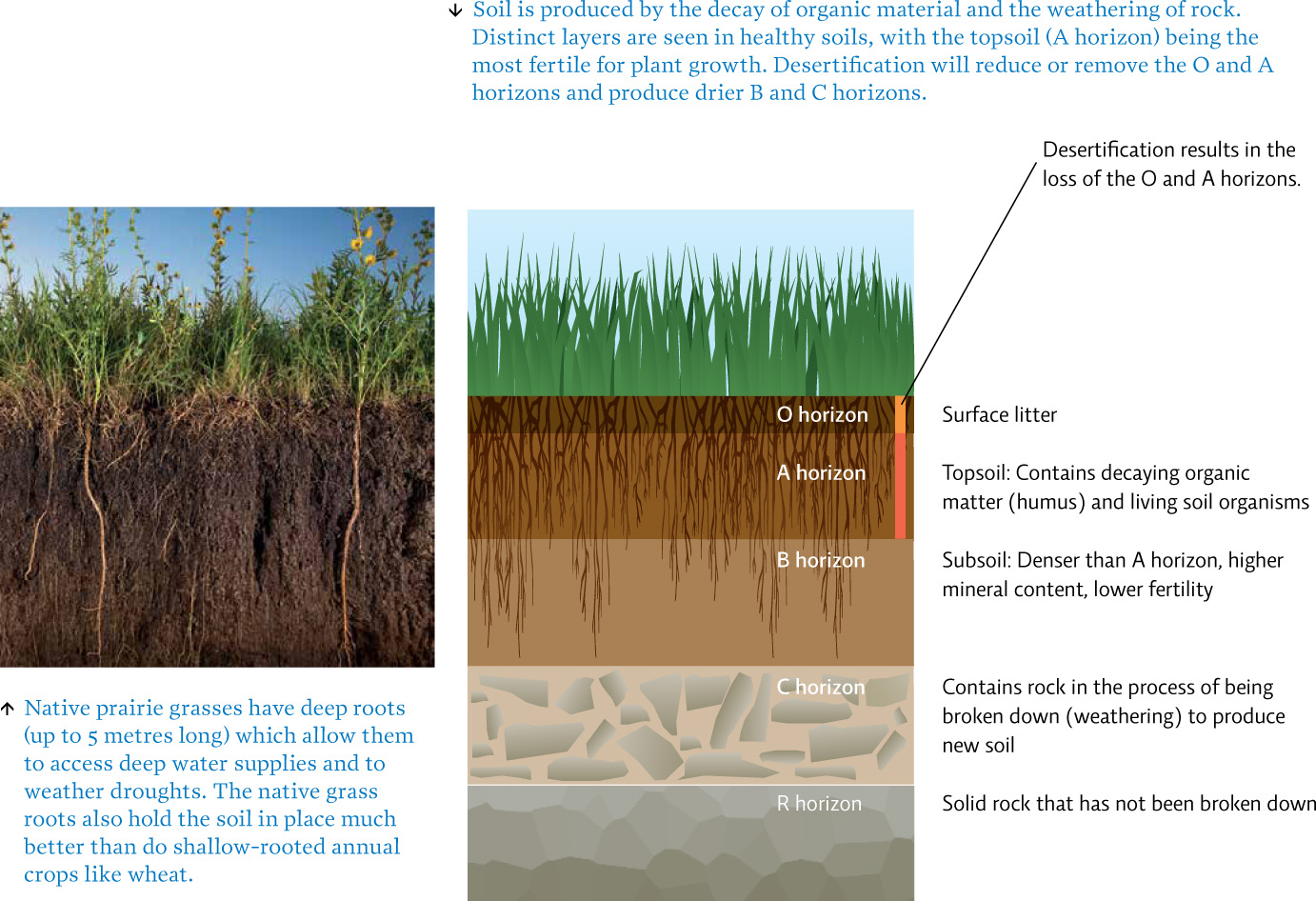

Together, plant loss and soil compaction increase the rate of soil erosion—a process in which soil is swept away by wind and rain down into streams, rivers, and gullies, faster than it can possibly be replenished. That’s no small matter. Soil formation is a slow process that requires the weathering of rock and decomposition of organic material. Under the best conditions, it takes 1 year to generate just a millimetre of the precious brown gold in which our food grows. A closer look at a soil’s profile sometimes reveals layers (called horizons) that reflect the formation process. As plants die out and soil erodes, the denuded landscape begins to reflect incoming sunlight rather than absorb it; this touches off a cascade that ultimately alters wind and temperature patterns. Before long, grasslands give way to deserts. [infographic 12.4]

210

211

At least once in North America’s history, human activities so amplified the speed and scope of desertification that it triggered the largest human migration inside a decade our continent has ever seen. Beginning in 1934, clouds of dust so massive that ranchers named them “black blizzards” swirled relentlessly across the Great Plains, tearing the paint off of houses and cars and forcing some 2.75 million homesteaders from the land. History named this time and place the Great Dust Bowl, and it became a classic example of the tragedy of the commons. As each individual homesteader expanded farm and ranch for his or her own gain, the land as a whole fell victim to overgrazing. When the next drought cycled through, there was no grass left to hold the crumbling soil in place.

It took nearly three decades for the prairies to recover, but according to some critics, only half as long for us to forget the Dust Bowl’s most important lessons. By the 1970s, with the market prices for agricultural goods rising steadily, many farmers were overplowing and overgrazing with the same pre-Dust Bowl fervour. Now, soil erosion is approaching Dust Bowl rates in some parts of the United States. Canada, which is not as susceptible as much of the drought-ridden United States, has held back the desert tide through regulations and farmer education on best practices.

So far, grassland degradation has cost humans roughly 12% of global grain production, not to mention $23 billion per year in global GDP (gross domestic product). All told, the food supply of more than 1 billion people is threatened. The Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) predicts that some 50 million people will be faced with displacement in the coming decades. The majority of these will be subsistence farmers who live in the world’s poorest regions and depend solely on cattle ranching for their livelihoods; but North American ranchers, like the ones who owned Horse Creek, will also suffer.

212

Scientists around the world have spent decades trying to prevent or even reverse desertification, to little avail. These days, most experts tend to agree that beyond a certain point, recovering grasslands that have swirled into deserts is impossible. “Most of our efforts to reverse desertification have failed dismally,” says Dr. Richard Teague, a research ecologist working with ranchers in West Texas to restore degraded rangeland. “But a number of ranchers here are having success with protocols developed halfway around the world.”