12.4 Taking our cues from nature, we can learn to use rangelands sustainably.

As the sun rises over Zimbabwe (formerly Rhodesia) in southern Africa, herds of antelope and zebra traverse a patchwork of temperate and tropical grasslands, feeding steadily on reedy stalks and short, fat shrubs; elephants and wildebeest splash around a precious watering hole, well fed and content. The animals may not realize it, but they have stumbled upon the Africa Centre for Holistic Management (ACHM), 2630 hectares of thriving rangeland in the heart of an otherwise parched and ailing savannah. [infographic 12.5]

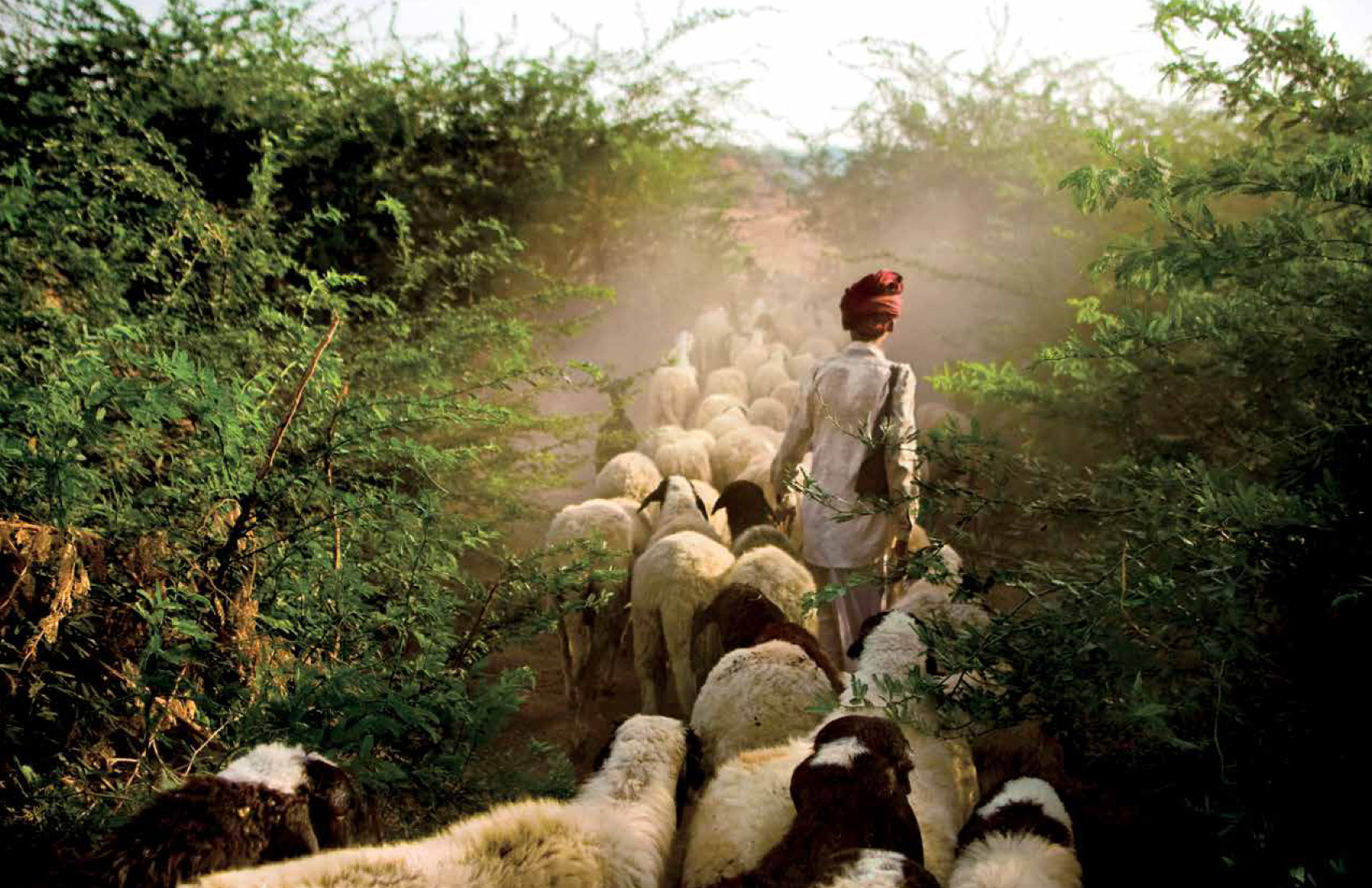

Perhaps nowhere else on Earth is such an oasis more urgently needed. Because the region is too arid to support much else, ranching provides the only livelihood for most of the people living there; about 75% of all land is used to graze domestic herds of cattle, goat, and sheep, and even that has not been enough. With population, and thus the number of mouths in need of food, rising steadily, farmers have crowded more and more livestock onto lands that grow sparser and drier by the day. Already stressed by climate change, that land is crumbling quickly into desert. And as viable pastures become increasingly difficult to find, neighbouring tribes have descended further into violent conflict—sometimes killing each other over a few stalks of grass.

The ACHM was established in 1992 by Allan Savory, a Rhodesian-born scientist-turned-rancher. Before then, the land had been so thoroughly desertified that neither wild nor domestic herds bothered to graze there. But in the nearly two decades since, the picture has changed dramatically. Both plants and wild herds have rebounded with surprising speed; even during the dry season, water is plentiful enough to sustain fish and water lilies. And if that’s not enough, livestock has increased by 400%. Ranchers come from around the world to marvel at the turnaround and to seek counsel from Savory, who is widely credited for the dramatic recovery.

Savory came by his expertise in a circuitous way. He spent the 1950s working as a research biologist and game ranger for the British Colonial Service. At the time, the British government was culling thousands of wild herds in an effort to create more land for farming. “Zimbabwe was infamous for the veterinary policy of shooting out all game over large areas,” Savory says. “The unofficial slogan was, ‘you cannot ranch in a zoo.’” That policy bred tension between ecologists like Savory who wanted to preserve the splendour of Africa’s natural environment, and ranchers and government officials who wanted to farm right over it. Like many of his colleagues, Savory developed a healthy disdain for the cattle that were slowly replacing his beloved zebra, elephants, and antelope, and a firm belief that the land he loved was being destroyed by cattle ranchers who crowded too many animals onto too little land.

213

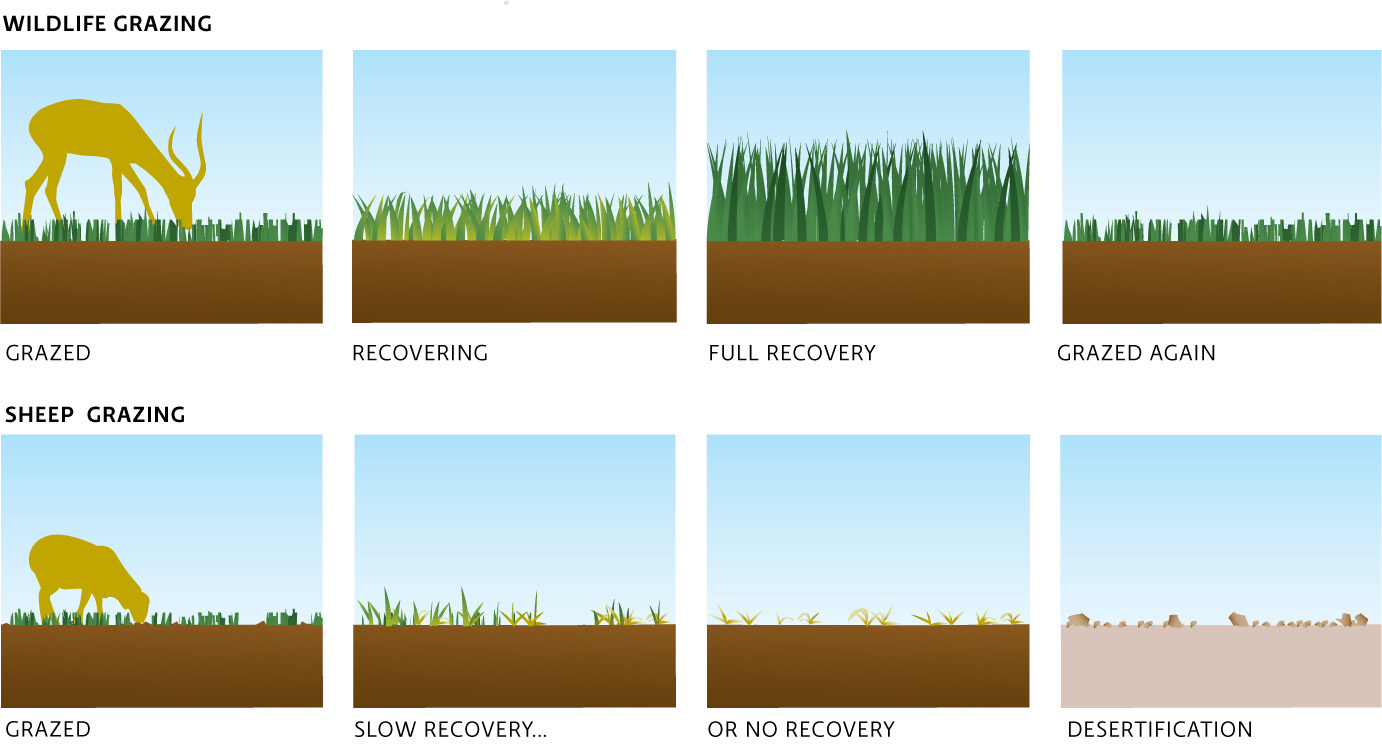

As he patrolled the vast terrain, Savory noticed that lands grazed by wild herds were healthier than those managed by cattle ranchers; plants were more abundant and diverse, rivers were cleaner and better stocked. “The wild herds were doing basically the same thing as the domestic herds,” he says. “They were eating the grass. But they were having the exact opposite effect.” He noticed that as they tried to protect themselves from predators and avoid feeding on their own feces, wild herds grazed in tightly bunched packs, and moved quickly from one patch of land to the next. They would stay just long enough to fertilize the ground with their waste and agitate the soil without compacting it, and they would not return until the dung had been absorbed and the land was clean again. This meant that grasses were heavily grazed over a short period, but then left for a long time to recover. The result: animals fed and grasses regenerated in an endless and mutually beneficial cycle. [infographic 12.6]

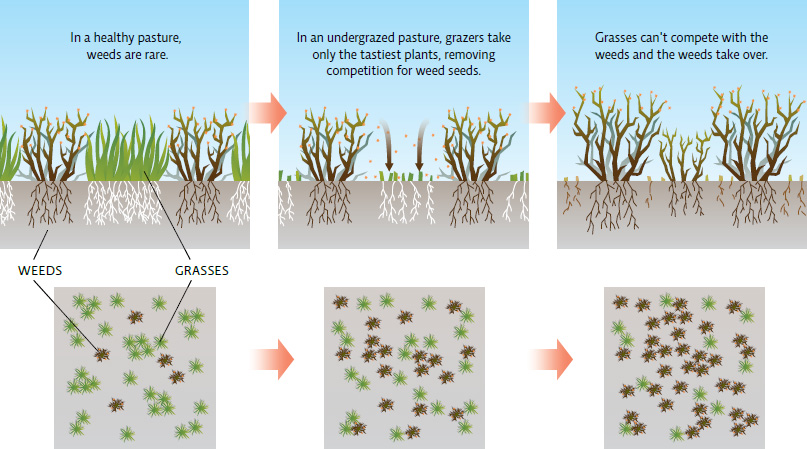

Once upon a time, pastoralists—individuals who herd and care for livestock as a way of life—mimicked the processes laid out by Mother Nature: grazing their stock in tight herds, moving them constantly across vast swaths of rangeland. But in the 19th and 20th centuries, ranchers began partitioning their grasslands into distinctly fenced-in pastures and dividing their livestock so as to control them more easily. This made ranching easier, to be sure. But as time wore on, farmers found that their lands were being overrun by shrubs and weeds. The cattle were selectively eating only the sweetest tasting grasses and leaving all the less palatable varieties to flourish. Season by season, the plant species composition shifted, and as it did, the land became less productive. Less sweet grass meant less cattle feed, which in turn meant thinner cattle, less food and, ultimately, thinner profits. And as scientists like Savory began to notice this, a simple idea took root: the lands were being destroyed because too many animals were feeding off of them. They decided that trimming the populations of both domestic and wild herds would be the key to salvation.

214

But, as scientists—including Savory himself—soon realized, undergrazing presented its own set of problems. “Where we culled too many animals, there was nothing to eat the grasses,” Savory says. “So they would die standing upright, and the detritus would prevent the sun from reaching the growth buds.” This also meant that instead of being returned to the soil through animals’ digestive tracts, nutrients would instead be processed by soil microbes—a much slower and thus less efficient process. And because there were fewer of them, animals could be more selective about which plants to eat; left untouched, unpalatable weeds and plants began to take over the pastures. [infographic 12.7]

North American ranchers were experiencing similar problems, and by the 1970s the farming industry had caught on. Land-grant universities in Texas and Arizona designed machines like the Dixon Imprinter that simulated the physical effects of large grazing herds—breaking soil crusts and laying down plant litter over vast swaths of pasture. Of course, those machines could not cycle nutrients the way animal digestive systems could, and so the colossal machine solved some problems (detritus no longer blocked the sun from growth shoots), but not others (soil quality still dropped because nutrients weren’t cycled as effectively).

Around the same time back in Africa, after two decades of surveying the land and observing both ranching and wild grazing in action, Savory was certain that ranching practices were contributing heavily to land degradation. He was equally certain that humans could reverse the process by managing the land differently—but he didn’t know exactly how. To figure it out, he would have to design and implement several different methods of ranching so that he could compare them to one another. And to do that, he would need to persuade the ranchers of Zimbabwe to let him experiment on their lands.

215

At first his imploring fell on deaf ears. Everyone agreed the lands were ailing, but government officials blamed the lack of rain, combined with overgrazing in some areas. Ranchers insisted they were already taking great care not to graze too many animals on too small a patch of land. What more could they do? “I went to the government scientists, and I tried talking to the ranchers themselves,” he says. “Nobody wanted to hear that they weren’t doing things in exactly the best way.”

Then one night, a couple of ranchers paid him a visit. They’d been doing everything the government advised, they said, and both their ranches, which sat side by side on the open plains of Bulawayo, Zimbabwe, had enjoyed ample rainfall that season. But their grasses were not rebounding and their businesses were suffering. Could he help them? “I told them I didn’t have any answers yet, just a sense that we were causing the land degradation ourselves, and that we could fix it by changing the way we ranched,” he says. “We agreed to be the blind leading the blind.”

Savory’s plan was based on biomimicry—grazing livestock the same way wild herbivores grazed. Borrowing some lessons from his time in the British Army, he devised a technique that called for controlling herds’ movements with military precision. He used electric fencing to divide the land into small paddocks, and then pulled all the livestock together into just one such paddock. Then he allowed the animals a day or two to eat everything they possibly could before releasing them into the next paddock. By that time, the first paddock had been churned into lumps of soil, dung, and freshly exposed growth buds. And so the herd would move, from paddock to paddock, devouring and fertilizing each patch of land as it went. By the time they had moved through the last paddock, they would be ready for market. Each paddock would then have an entire season—roughly 180 days, depending on how the rains fell that year—to recover.

216

The concept was not entirely new. Rotational grazing—where animals are allowed to graze on a small section of pasture for a few days before being moved to another section—was first introduced by scientists of the 18th century and has since gained widespread acceptance by ranchers around the world. But so far, the technique had done little to restore plant biodiversity or stop the transformation of grassland into desert.

Savory’s plan was based on biomimicry—grazing livestock the same way wild herbivores grazed.

Savory says that the most widely used rotational grazing methods focus too heavily on limiting the number of animals allowed to graze and not enough on the amount of time they spend grazing any given patch of land. Overgrazing, he says, is a function of time, not numbers. In fact, he says, high stock densities are actually better for the land because they reduce animal selectivity (that is, hungry animals crowded together will eat whatever they can get their teeth on, including the less sweet-tasting varieties of grass that would normally be left to overtake the pasture) and thus help preserve biodiversity. “The results we are seeing at our centre today are because of a 400% increase in the number of animals we graze, not despite it,” he says. “I have to make that point to almost every scientist and rancher that passes through.”

In 1960s Zimbabwe, degraded land gave way to starving people and civil unrest. Amid this turmoil, Savory and his wife were exiled, along with hundreds of others whom the government decided were activists or political dissidents. They took their work to the United States, where they found a surprisingly similar state of land-use affairs. Government agencies and land-grant colleges around the country scoffed at the idea of increasing the number of livestock as a means to combating desertification. But as individual ranchers caught wind of Savory’s work, they began seeking him out.