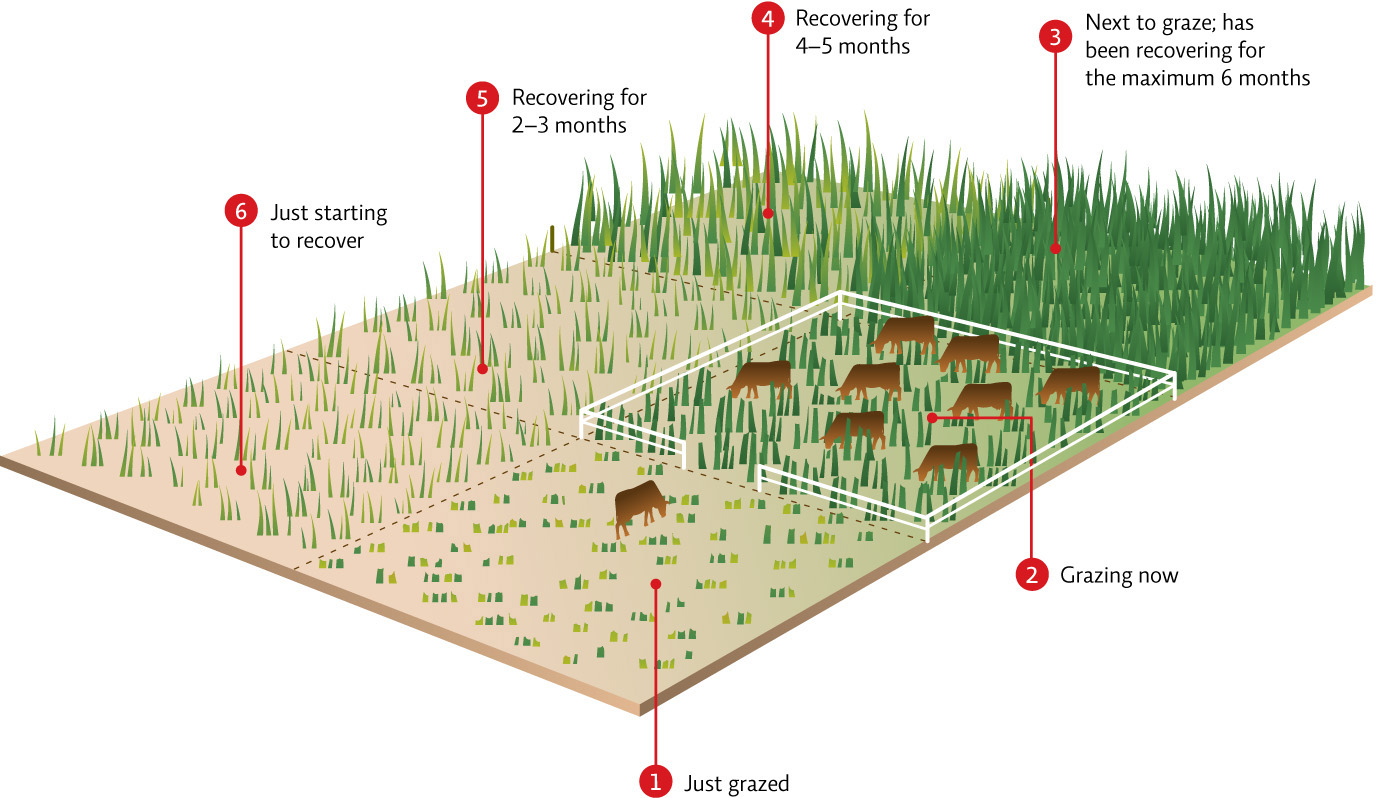

12.5 Counteracting overgrazing requires careful planning.

One of these ranchers was Jim Howell. Howell had grown up on his family’s ranch in Colorado, and was studying to be a veterinarian when he came across Savory’s work in the mid-1990s. “I saw quickly that the way my family had managed the land, going back to when they first bought it in 1937, was hurting it,” he says. “We were losing biodiversity, losing soil, and every year the land was yielding up less profits than it had the year before.” Convinced that being a good rancher meant being a good ecologist, Howell switched majors, became an ecologist, and promptly began looking for opportunities to put Savory’s methods to the test.

Eventually, he partnered with a group of investors to create Grasslands, LLC, a private equity fund whose aim is to buy up failing ranches throughout the Great Plains region and use Savory’s holistic management techniques to resuscitate them. In 2010, the group made its first purchase: Horse Creek and a neighbouring ranch that together hold 60 square kilometres of degraded South Dakota rangeland.

With careful planning, Howell’s ranching team can work around several seasonal constrictions at once, including water availability, the bloom cycles of poisonous plants, and the migration patterns of various wild animals. Not returning to the same small paddock for a full year also breaks the reproductive cycle of many parasites. And keeping animals tightly bunched for a set period of time ensures that all plants are grazed equally—not just the sweetest grasses, but the weeds, too. This actually gives the better-tasting plants an advantage: because they don’t waste as much energy on chemical defences (which is what makes some plants so unpalatable in the first place), they regrow faster and thus colonize more area than the foul-tasting plants.

On top of that, planned grazing helps keep plant biomass levels within an ideal range, where plants capture a maximum amount of sunlight and thus grow exceedingly quickly. Below this range, plants have less leaf area, capture less solar energy, and grow much more slowly as a result; above it, excessive leaf growth blocks newer shoots from the sun, and old leaves die as fast as new ones are made. Grasses kept between these two extremes regenerate much more quickly and are thus ideal for grazing. [infographic 12.8]

Howell says the end result of such careful planning is that land productivity is maximized and ranching becomes profitable once again. So far, the numbers support his claim. According to one assessment of Alberta’s grazing practices, by Warren Elofson of the University of Calgary, rotational grazing decreases land needed per cow by two thirds. “You’re raising twice as many animals in the same amount of space,” explains Howell. “It’s like getting a second ranch for free.”

In fact, the financial benefits have proven so substantial, Howell and his partners are betting that the economy will rebound in tandem with the land. “Ultimately, we want to sell these places back to the surrounding communities,” says Howell. “At the very least, we hope to inject some energy into the region—provide jobs, attract young people.”

217