12.6 Planned grazing is tricky work.

But planned grazing is tricky work, especially for ranchers who are set in their ways and are already anxious about the bottom line. “It’s very hard to make a ranch profitable in the first place. So significant change can be very frightening,” says Howell. In more traditional grazing methods, animals are left in the same pasture for long periods, sometimes for an entire growing season, which can run for as long as 180 days. With planned grazing—as Savory’s method is called—animals are moved much more frequently. “It’s really easy to screw things up when you switch from regular grazing to planned grazing,” Howell, adds. “It’s easy enough if you have 3 pastures and a 180-day growing season—each pasture gets about 60 days of grazing and 120 days of recovery,” Howell says. “But say you have 45 pastures. That’d give you an average grazing period of only 4 days. If you’re off by even a day, your animals can suffer considerably.” Leave them on a given pasture too long, and they will run out of food. Do that too often, and the animals’ ability to gain weight, lactate, come into heat, and reproduce will all be compromised. And that can take a huge economic toll.

Not everyone agrees the risk is worth it. Most ranchers acknowledge that sustainable grazing–grazing that maintains the health of the ecosystem and allows the grasses to recover before the animals return—is essential to protecting grasslands the world over. But some argue that existing methods of continuous grazing work just as well, if not better, when done properly. “There is plenty of evidence showing comparable outcomes for biodiversity, soil erosion, etc.,” says David Briske, a rangeland ecologist at Texas A&M University. “Effective management of grazed ecosystems is sufficiently dynamic and complex that it should not be envisioned to have any one correct solution.”

218

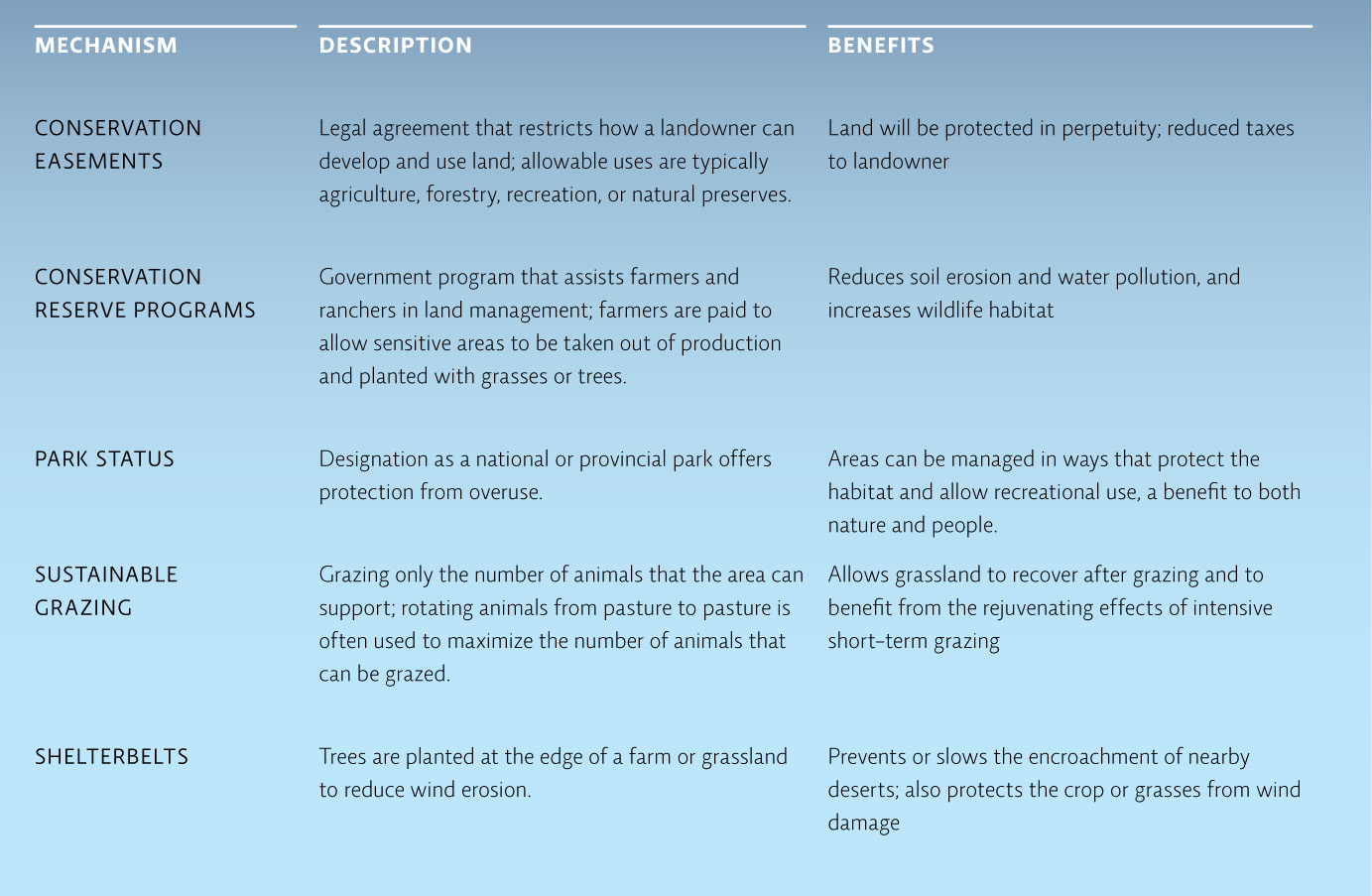

Grasslands are not just here for human use and anything we can do to restore or protect them will benefit us and other species as well. Savory is showing that improved grazing techniques can help protect and even restore some degraded grasslands. Another land-management technique that also reduces soil erosion and protects grasslands from degradation is the planting of shelterbelts—a stand of trees that blocks the wind and thus decreases wind erosion. Shelterbelt programs helped Canada and the United States recover from the Dust Bowl and are being used today in areas facing desertification, such as Inner Mongolia and China (where the shelterbelt is referred to as the “Green Wall of China”). Other approaches, such as conservation easements, reserves, and protected parks also help protect our grasslands by limiting land uses and making it easier to keep grasslands in some level of protected status. [infographic 12.9]

Nevertheless, a growing number of Canadian and U.S. ranchers are following Howell’s and Savory’s lead. Success in Zimbabwe has been followed by successes in California, Texas, Alberta, and Ontario. “Change is tough,” says Joe Morris, a rancher in central California who has been using Savory’s methods with great success. “Ranching is a culture, steeped in tradition. But our lands are hurting and our communities are dying, and we know we’ve got to do something to fix that.”

This past spring, Howell and his partners ran 2300 yearling cattle out of Horse Creek Ranch—a nearly 100% increase from years past and a number they hope to double next season. “It’s going to be a long road,” says Howell. “But we’ve already made so much progress, in just one season.” Meanwhile, back on the range, tiny buds of grass have begun to poke up everywhere.

Select references in this chapter:

Bailey, D.W., et al. 1996. Journal of Range Management, 49:386–400.

Briske, D. D., et al. 2011. Rangeland Ecology and Management, 64:325–334.

Briske, D. D. et al. 2008. Rangeland Ecology and Management, 61:3–17.

Derner, J.D., & Hart, R.H. 2007. Rangeland Ecology and Management, 60:270–276.

Diaz-Solis, H., et al. 2003. Agricultural Systems, 76:655–680.

Elofson, W. 2012. Agricultural History, 86(4): 144-168.

Heitschmidt, R.K., et al. 2005. Rangeland Ecology and Management, 58:11–19.

Savory, A., & Parsons, S. 1980. Rangelands, 2:234–237.

219

BRING IT HOME: PERSONAL CHOICES THAT HELP

Because of overgrazing and rampant soil erosion, the grasslands have lost a larger proportion of their habitat than the tropical rainforests. But most people have never worried about preserving the grasslands, let alone are even aware of how little remains (only about 1–2%). Grassland habitats provide many ecosystem services—they capture CO2 and are home to an immense range of biodiversity. They can be used for both economic growth as well as recreation, but only if they are managed properly.

Individual Steps

Visit a remnant or restored prairie. Such prairie preserves are scattered throughout the heart of North America, ranging from Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba in the north, down through the Great Plains to southern Texas and Mexico, and from the Rocky Mountains eastward to western Indiana. There are more than 20 national grasslands and several dozen more provincial, state, and local prairie preserves.

Visit a remnant or restored prairie. Such prairie preserves are scattered throughout the heart of North America, ranging from Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba in the north, down through the Great Plains to southern Texas and Mexico, and from the Rocky Mountains eastward to western Indiana. There are more than 20 national grasslands and several dozen more provincial, state, and local prairie preserves.

Explore the difference between turf grass and native grasses. Find out what grasses are native to your area and plant some in your yard.

Explore the difference between turf grass and native grasses. Find out what grasses are native to your area and plant some in your yard.

Purchase grass-fed beef or free-range bison meat as a way to support sustainable use of grassland ecosystems.

Purchase grass-fed beef or free-range bison meat as a way to support sustainable use of grassland ecosystems.

Group Action

If there are prairie restoration efforts underway in your community, participate in these efforts, which include seeding, brush cutting, removal of invasive species, and seed collecting.

If there are prairie restoration efforts underway in your community, participate in these efforts, which include seeding, brush cutting, removal of invasive species, and seed collecting.

Policy Change

Research national legislation designed to protect and restore native habitats like grasslands and write a letter to your provincial representative asking him or her to vote for the legislation.

Research national legislation designed to protect and restore native habitats like grasslands and write a letter to your provincial representative asking him or her to vote for the legislation.

Organize a fundraiser and donate the proceeds to research that examines the pros and cons of using grasslands for either biomass production or wind farms.

Organize a fundraiser and donate the proceeds to research that examines the pros and cons of using grasslands for either biomass production or wind farms.

220