13.1 Aquanauts explore an ecosystem on the brink

| CHAPTER 13 | MARINE ECOSYSTEMS |

SCIENCE UNDER THE SEA

222

223

CORE MESSAGE

Marine ecosystems contain a huge diversity of life, though we know far less about ocean ecosystems than those on land. Many ocean ecosystems are suffering as a result of pollution, overfishing, misuse of the ecosystem’s resources, and global climate change. Of particular concern is the change in ocean chemistry caused by the release of CO2 from fossil fuel use. This has the potential to alter ocean ecosystems drastically, and some effects are already being seen. Choices we make today will influence the future of ocean ecosystems and the species that inhabit them.

GUIDING QUESTIONS

After reading this chapter, you should be able to answer the following questions:

What is contributing to ocean acidification and why is this a problem?

What is contributing to ocean acidification and why is this a problem? What environmental conditions determine the location and makeup of marine ecosystems?

What environmental conditions determine the location and makeup of marine ecosystems? Where are coral reefs found and what is the community makeup of these complex ecosystems?

Where are coral reefs found and what is the community makeup of these complex ecosystems? What threats do coral reefs and other ocean communities face?

What threats do coral reefs and other ocean communities face? How can we reduce the threats to coral reefs and other ocean ecosystems?

How can we reduce the threats to coral reefs and other ocean ecosystems?

224

225

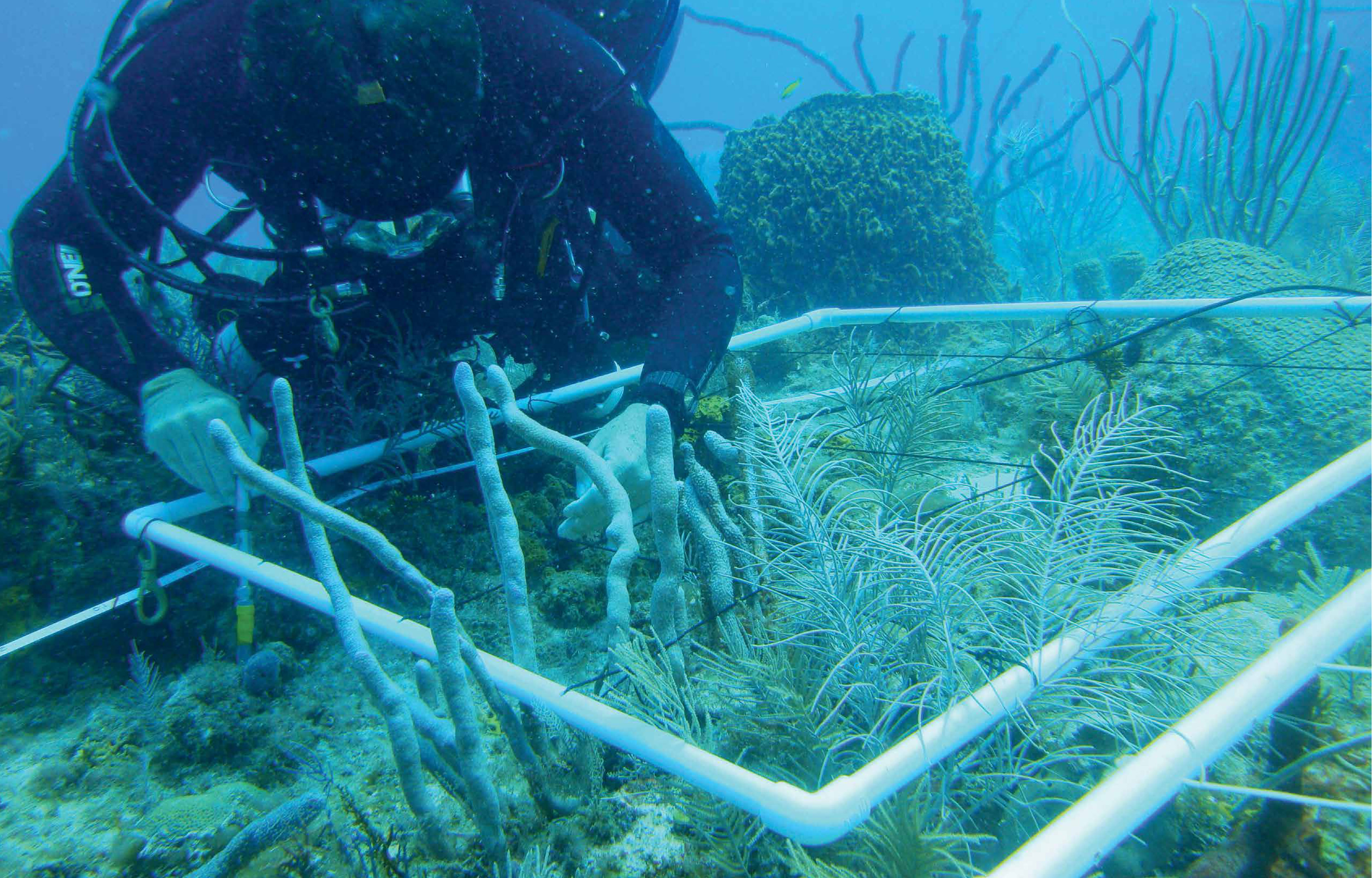

It was four o’clock in the morning and Marc Slattery could not sleep. He and his six crewmates had just settled into the Aquarius Reef Base— an artificial, undersea research station located on Conch Reef, 16 kilometres off shore from, and 15 metres below, Key Largo, Florida. Tomorrow they would begin an 8-day stretch of underwater experiments and data collection—all aimed at understanding how the physiology of various coral reef species was changing in response to changes in ocean conditions. Slattery, a scientist at the University of Mississippi and the team’s principal investigator, was anxious to get started.

But it was not this eagerness keeping him awake; it was the two goliath groupers—each about 2.5 metres in length—gliding persistently past the viewport near his bunk. Sticking close to one another, they would swish up to the small circular window, stare at him briefly, and then swish away to complete another lap around the structure. Slattery was captivated. As a young kid, he had spent countless hours watching a collection of tropical fish glide around his home aquarium. Now, for the first time, he knew how the fish must have felt. “They seem to swim back and forth between the bunkroom and galley viewports looking for those fascinating creatures that walk on two legs, breathe air and eat constantly,” he wrote in the expedition log. “They accept our odd behavior and even seem to enjoy our presence. Maybe they know we are here to help.”

Whether they knew it or not, the groupers, and all of their underwater neighbours, were being threatened by an avalanche of forces—global climate change chief among them. Around the world, temperatures were rising, glaciers melting, and the ocean’s chemistry changing in peculiar and disturbing ways. Scientists like Slattery had been on a quest to understand these changes from their land-based labs. Now Slattery wanted to dig for clues down below.