13.5 Coral reefs are complex communities with lots of interspecific interactions.

Species of coral reef communities interact with and depend on each other in many ways (see Chapter 8). Clown fish and sea anemones offer each other both food and protection (mutualism); remora fish attach their suckers to manta rays and eat any bits of food that flow out of the ray’s mouth (commensalism); and sea urchins act like lawn mowers, feeding on the reef itself in a way that enables new corals to attach and grow, thereby keeping the overall structure strong and healthy.

234

Like kelp, coral reefs attract and provide food and habitat for many other species. In fact, scientists estimate that 25% of all ocean species spend at least some portion of their life in a coral reef. This outsized role in marine ecology makes reefs an appealing target for oceanographers to study, and is but one of several reasons that the Aquarius station was positioned near a reef. “Coral reefs are the ultimate keystone species,” says Martens. “Understanding them is the key to understanding everything else that’s going wrong in the ocean right now.”

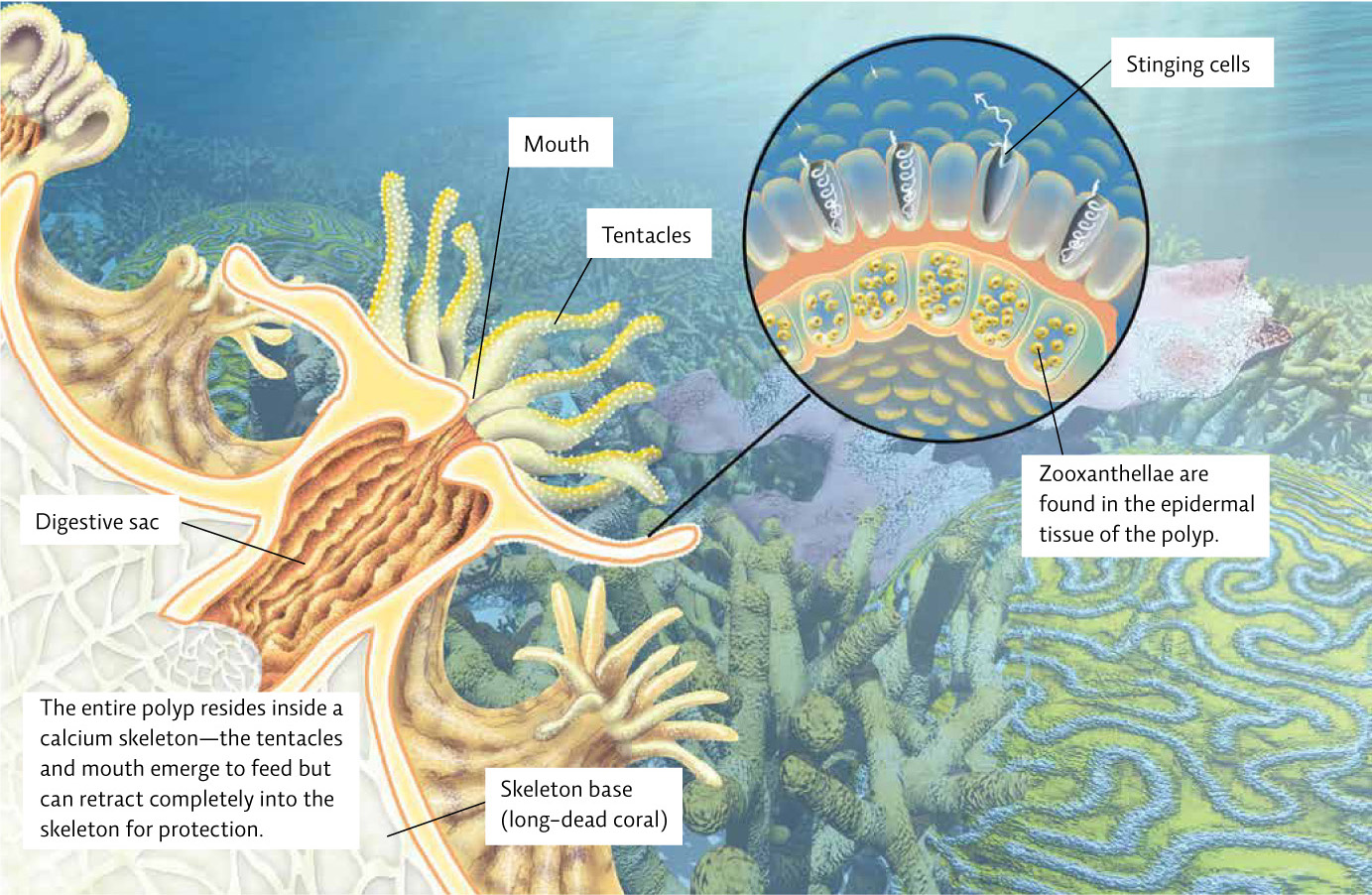

Corals are tiny marine organisms that live in densely packed colonies of many individual polyps (basically a tube with one opening surrounded by tentacles). Coral larvae (immature stage) are free floating but must attach to a surface to survive. Established coral reefs actually attract the larvae via chemical cues, increasing the odds that the larvae will attach to and build on top of existing coral skeletons. Once attached to a surface, the larvae enter the polyp stage and secrete a calcium carbonate skeleton. A reef thus grows from corals building on top of other corals over the course of generations. Studies have also shown that lower pH leads to declines in fertilization, in larval development, and in a process called settlement—the dropping of coral larvae out of the water column, and their attaching to something solid—the necessary prerequisites to new coral colony formation.

235

Corals feed on decaying organic material and plankton—pretty much anything that floats by. But they live in nutrient-poor regions: tropical waters tend to remain stratified, with warm water trapped above colder, deeper water. This stratification prevents the mixing of deep water and surface water that would normally bring up nutrients from below.

Thus the corals themselves could not survive without some help from their algal partners. They live in a mutualistic relationship with zooxanthellae (known affectionately to most marine biologists as “zooks”)—a photosynthetic, dinoflagellate algae that lives inside, and shares nutrients with, the coral. Corals provide their resident zooks with nutrients (from the polyps’ waste) and CO2 for photosynthesis. Zooks, in turn, provide the coral polyps with food (sugars made during photosynthesis). The zooks also give the corals their beautiful colours. It’s a well-honed evolutionary collaboration, one that enables each species to thrive in a nutrient-poor environment. [infographic 13.5]

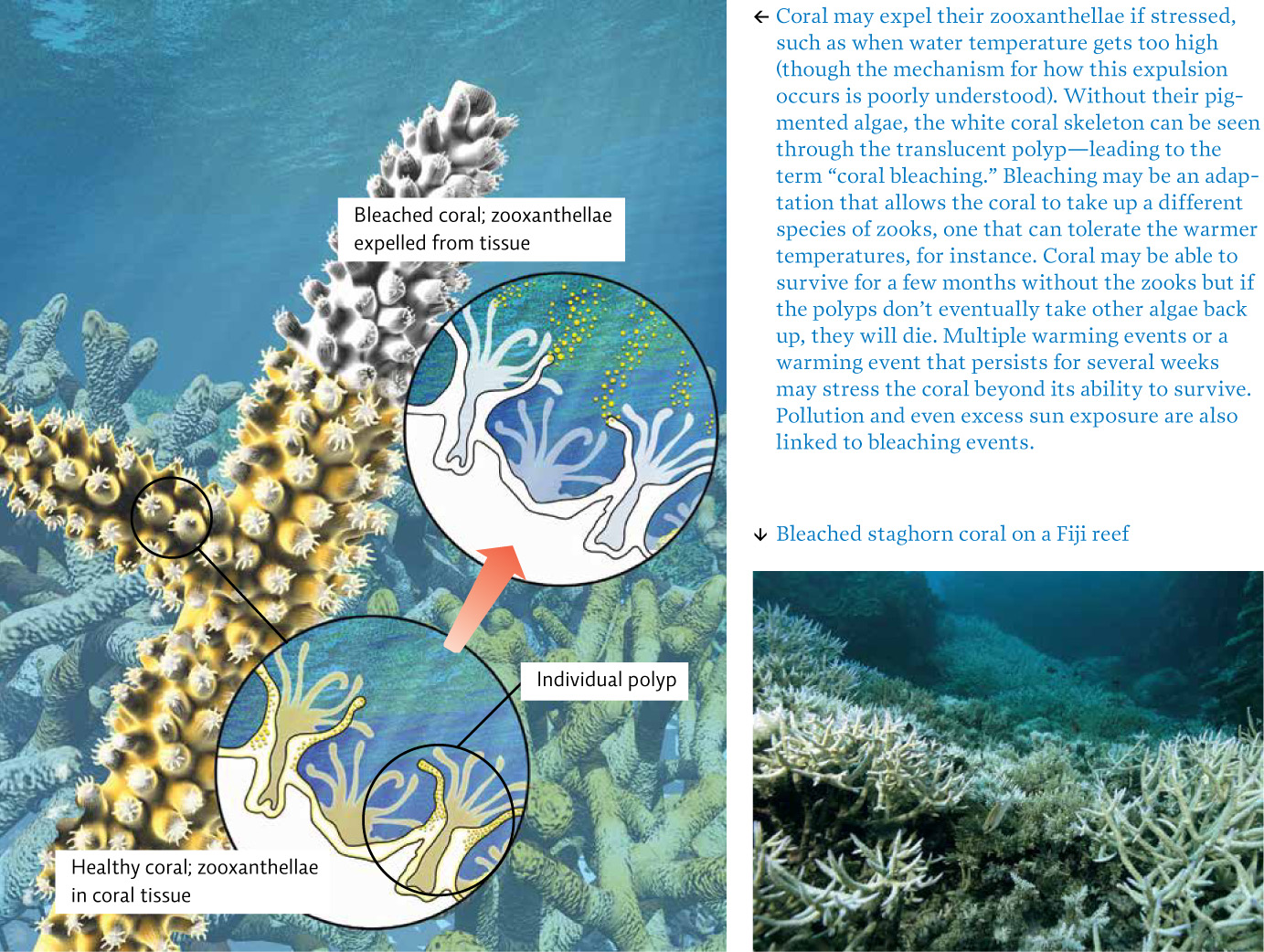

Corals can also control the number of zooks they host in their cells by adjusting the amount of sunlight or nutrients they supply. Under extreme stress, corals have been known to expel the algae. This event is known as coral bleaching because when it happens, the coral turns bone white. Though the coral can survive for a short period of time without zooks, they will die if not recolonized. Since the many species of zooks are symbiotically tied to their coral hosts, any events that lead to coral death, such as bleaching or decalcification, could also lead to the loss of the zooxanthellae species that reside in those coral. [infographic 13.6]

236

Scientists have found that in the past, corals have gone through natural death and birth cycles in response to environmental changes such as shifts in temperature or pH. However, many scientists feel that today’s accelerating rates of acidification and bleaching are likely unprecedented, as is their global scope. But CO2-related effects are by no means the only threats.