14.1 How one fish scientist could change the way we eat

| CHAPTER 14 | FISHERIES AND AQUACULTURE |

FISH IN A WAREHOUSE?

242

243

CORE MESSAGE

Although the oceans are vast, many fisheries are in serious jeopardy due to overfishing. Aquaculture may allow us to raise fish for harvest, taking some pressure off of wild stocks.

GUIDING QUESTIONS

After reading this chapter, you should be able to answer the following questions:

How are fish and fisheries like that of the Atlantic cod important for humans?

How are fish and fisheries like that of the Atlantic cod important for humans? How do technology and the tragedy of the commons interact to jeopardize global fisheries?

How do technology and the tragedy of the commons interact to jeopardize global fisheries? Why have fisheries declined so precipitously in the last half-century and what is the current status of the world’s fisheries?

Why have fisheries declined so precipitously in the last half-century and what is the current status of the world’s fisheries? What are some of the ways we are trying to protect our fisheries?

What are some of the ways we are trying to protect our fisheries? What is aquaculture and how might it ease the strain on at-risk fisheries? What trade-offs does aquaculture involve?

What is aquaculture and how might it ease the strain on at-risk fisheries? What trade-offs does aquaculture involve?

244

In Frenchman Bay, Maine, eight fishers huddle around their aquaculturist instructor as he explains how to feed the “fingerling” cod, each about 40–60 millimetres long, in the wired cage beneath the water. The group is part of a new program meant to turn fishers into fish farmers. Instead of harvesting wild fish from the depths of the ocean, with factory ships and huge fishing nets, the fishers will learn how to raise them, from hatchlings to full-sized adults—how to feed them, monitor their health, and ultimately, how to prepare them for sale. Today, the fishers are observing a coastal net pen, where fish are raised in a system of stationary, floating nets, usually positioned in coastal waters. Tomorrow they will tour an indoor fish farm where the same types of fish are raised in colossal indoor tanks.

This, say experts, is the future of fishing.

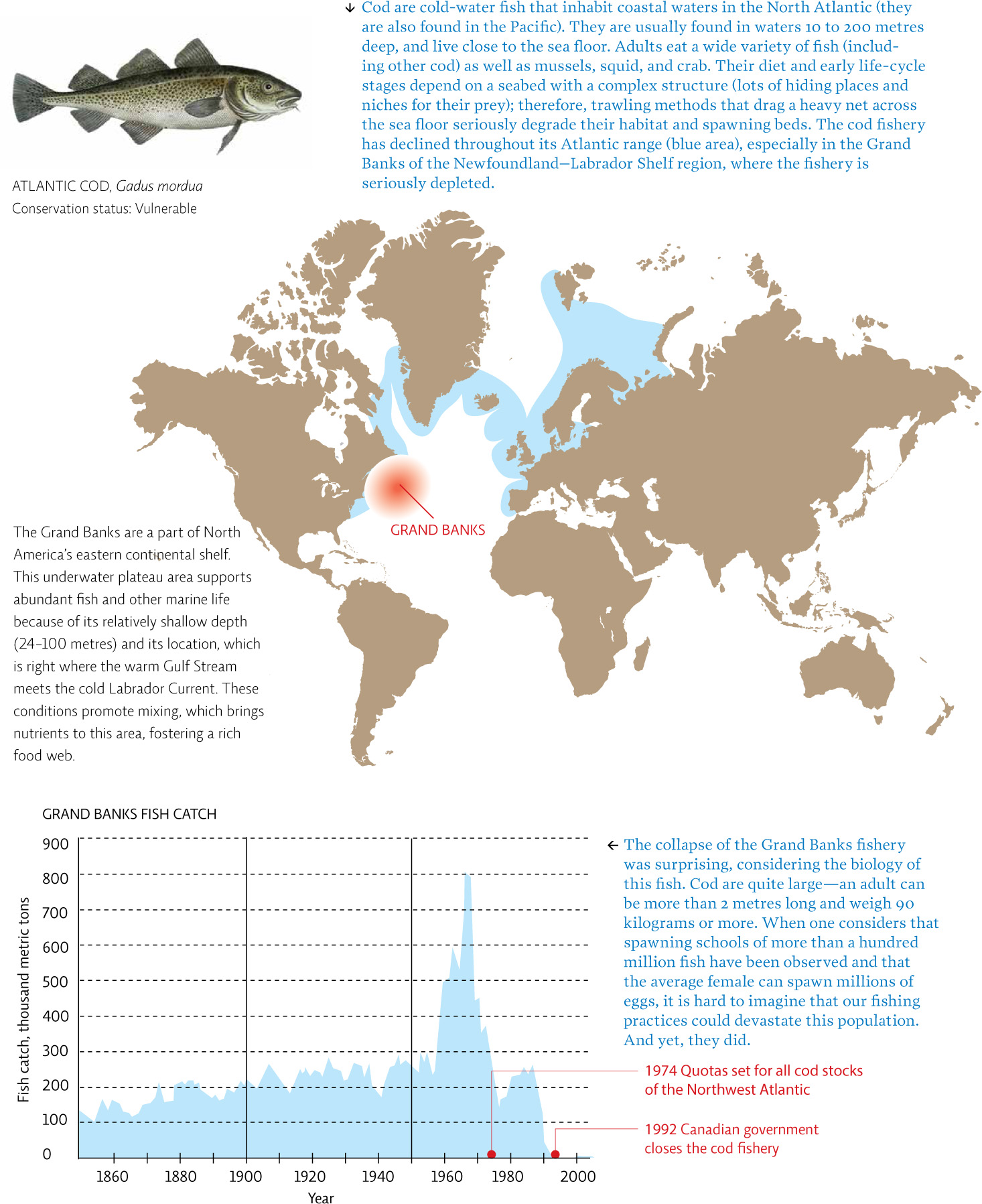

For more than 400 years, the Atlantic cod—a demersal fish that feeds along the ocean floor—supported not just a fishing industry, but an entire culture along the northeastern coast of North America. Huge fisheries—operations in which fish are caught, harvested, processed, and sold and/or shipped—sprang up in the port towns of Newfoundland, New England, and even European countries, and were sustained for generations almost exclusively by this one fish. Cod became a crucial part of the early Newfoundland economy. Up to 400 000 metric tons of cod were caught each year in the 1800s and, justifiably, cod earned the name “Newfoundland currency.” But after a dramatic peak in the late 1960s, catches declined rapidly. The Canadian government imposed quotas in 1974, but by 1992 the annual catch had dropped to just 2% of its historic high and the federal government closed the Grand Banks area to fishing completely. When annual catches fall below 10% of their historic high, scientists call this a collapsed fishery. [infographic 14.1]

More than 20 years later, with the moratorium still in place, the Grand Banks cod fishery has yet to recover. Cod population estimates still hover at around 30% of what would be needed for the fishery to survive commercial fishing pressure. Meanwhile, some 40 000 cod fishers are still out of work and reliant on government support.

How did this happen? One reason is that nobody owns the ocean’s resources but everyone uses them; the collapse of the Grand Banks cod fishery is a classic example of the tragedy of the commons (see Chapter 1). Trawlers from Canada, the United States, and several western European nations all fished the Grand Banks and contributed to the cod fishery collapse.

245

246

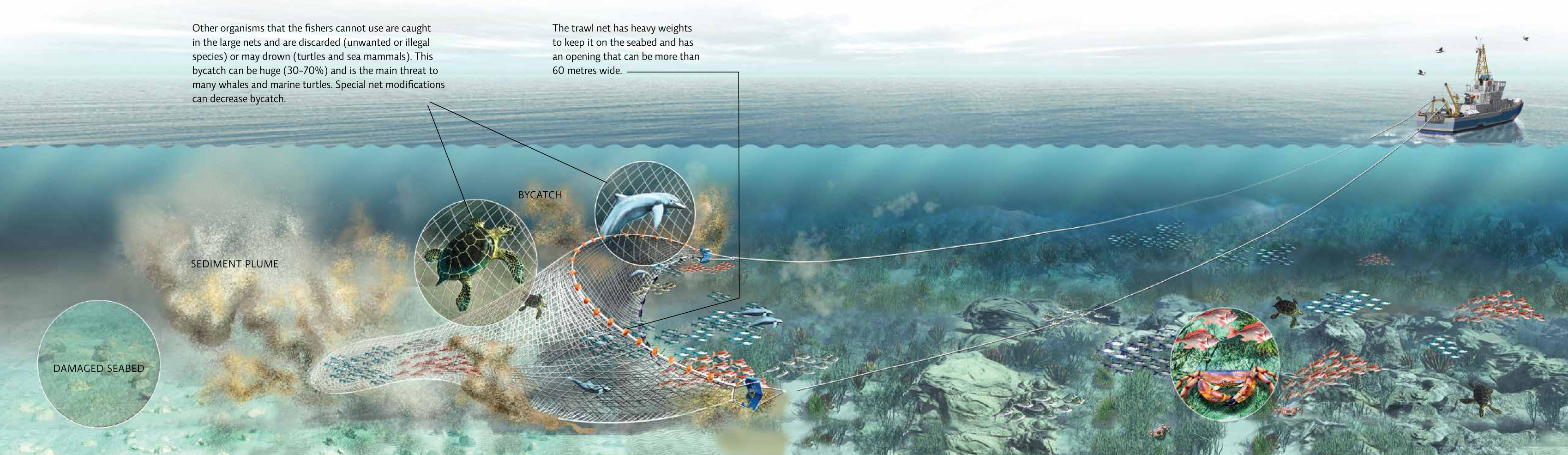

Another reason for the fishery’s collapse involves a trifecta of technological advances—steam engines, flash freezing, and trawler ships that could drag huge nets behind them—that enabled fishers to travel farther into the ocean, catch more fish, and transport those fish greater distances than ever before. At the same time, health-conscious eating patterns made fish more popular than any other source of protein. With the coalescence of new technology, rising demand, and multiple fishing nations, the once-prolific Grand Banks cod fishery was decimated. Fish populations plummeted, and the increased traffic of fuel-guzzling ships polluted the water. Bottom trawlers are particularly damaging. They destroy the sea beds, which are the cod’s spawning grounds, and catch or destroy billions of coral, sponges, starfish, and other invertebrates.

Other marine species are lost as bycatch, meaning they are trapped in the trawler nets that are meant to capture cod. Being caught as bycatch seriously threatens many species, including small whales and dolphins (over 300 000 lost per year), sea turtles (over 250 000 lost per year), and even seabirds (over 300 000 lost per year). Seals, sea lions, and sea otter populations have declined by as much as 85% in some areas due to this unintentional capture. Non-target fish are also taken as bycatch, including sharks, rays, and juvenile fish of many species, including cod. Bycatch is also a problem with other industrial fishing techniques such as long-line fishing (where a main line holds many individual lines with baited hooks) and drift netting (where a free-floating net entangles fish; this method was banned in 1992). Fishing methods that minimize bycatch are available and their use is increasing. [infographic 14.2]

Such is the story of our last wild food. It begins in the oceans and ends on our dining room tables. But as fish stocks around the world—not only of Atlantic cod, but also of Chilean sea bass, Alaskan pollock, bluefin tuna, and Atlantic herring—dwindle to unprecedented lows, scientists and fishers alike are trying to rewrite that story. Their success could mean sparing the world’s fisheries from an unthinkable fate; but it could also mean that our grandchildren never eat a wild caught fish.

247