15.2 Water is one of the most ubiquitous, yet scarce, resources on Earth.

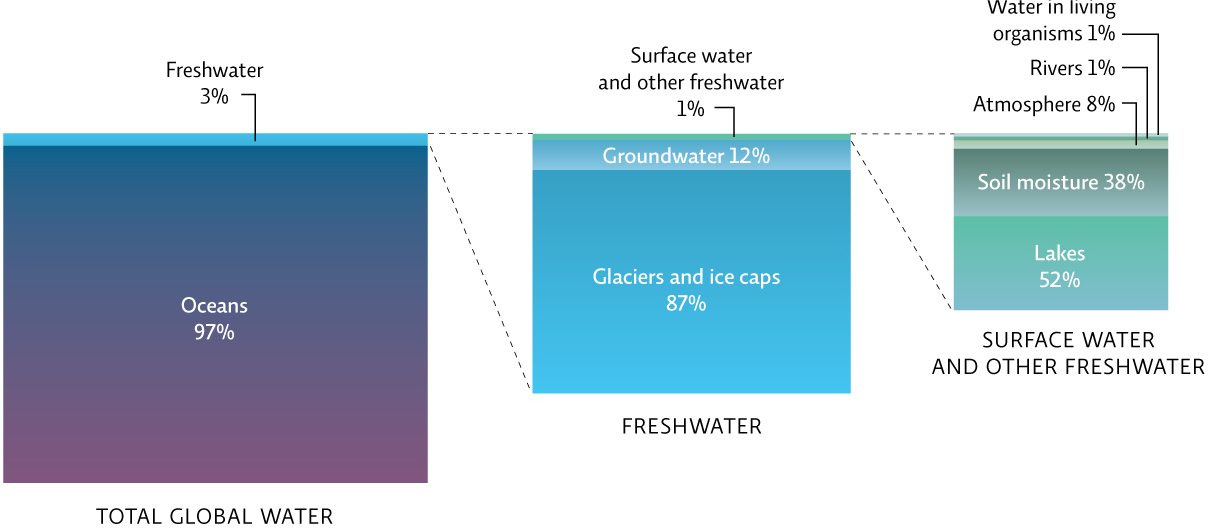

Even though Earth is covered in more than 1400 million cubic kilometres of water—about 75% of its surface—only about 1/100 of 1% of that water is usable by humans.

Water provides many important ecosystem services that animals and plants require to live. Up to 75% of the human body, for instance, consists of water. But humans need liquid freshwater (which has few dissolved ions such as salt); ocean water is too salty for human consumption and is toxic in large doses.

WHERE IS ANAHEIM, CALIFORNIA?

Complicating things, nearly 80% of the freshwater on the planet is trapped in ice caps at the poles and glaciers around the world, which contain more than 35 million cubic kilometres—enough to fill 140 billion Olympicsized swimming pools. [infographic 15.1]

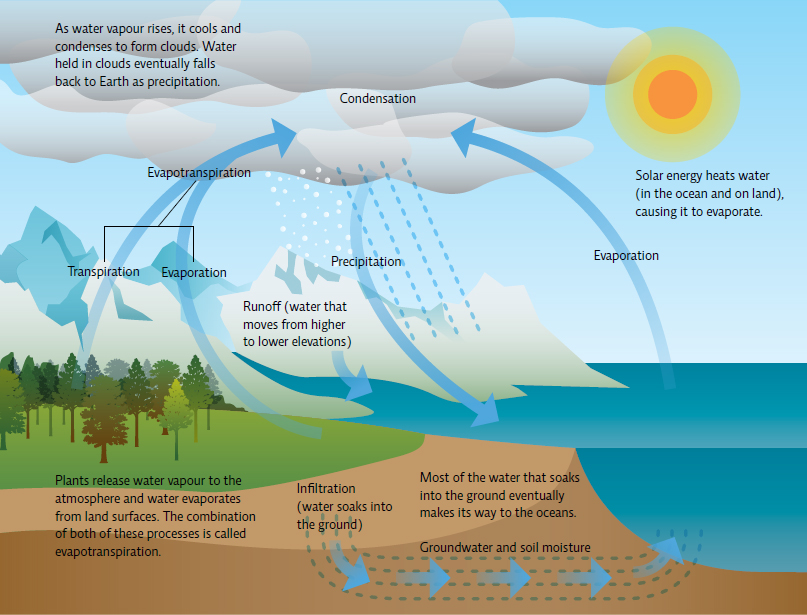

Wherever there is water, it is constantly moving through the environment via the water cycle (hydrologic cycle). Heat from the sun causes water to evaporate from surface waters (rivers, lakes, oceans) and land surfaces. At the same time, plant roots pull up water from the soil and then release some into the atmosphere in a process called transpiration. Plants with deep roots, like trees, may bring up many thousands of litres of water a year, releasing much of this to the atmosphere. Altogether, the combination of evaporation and transpiration— evapotranspiration—sends more than 64 000 trillion litres of water vapour into the atmosphere every year. Once aloft, that water condenses into clouds (condensation) and may fall back to Earth as precipitation (rain, snow, sleet, etc.). [infographic 15.2]

263

264

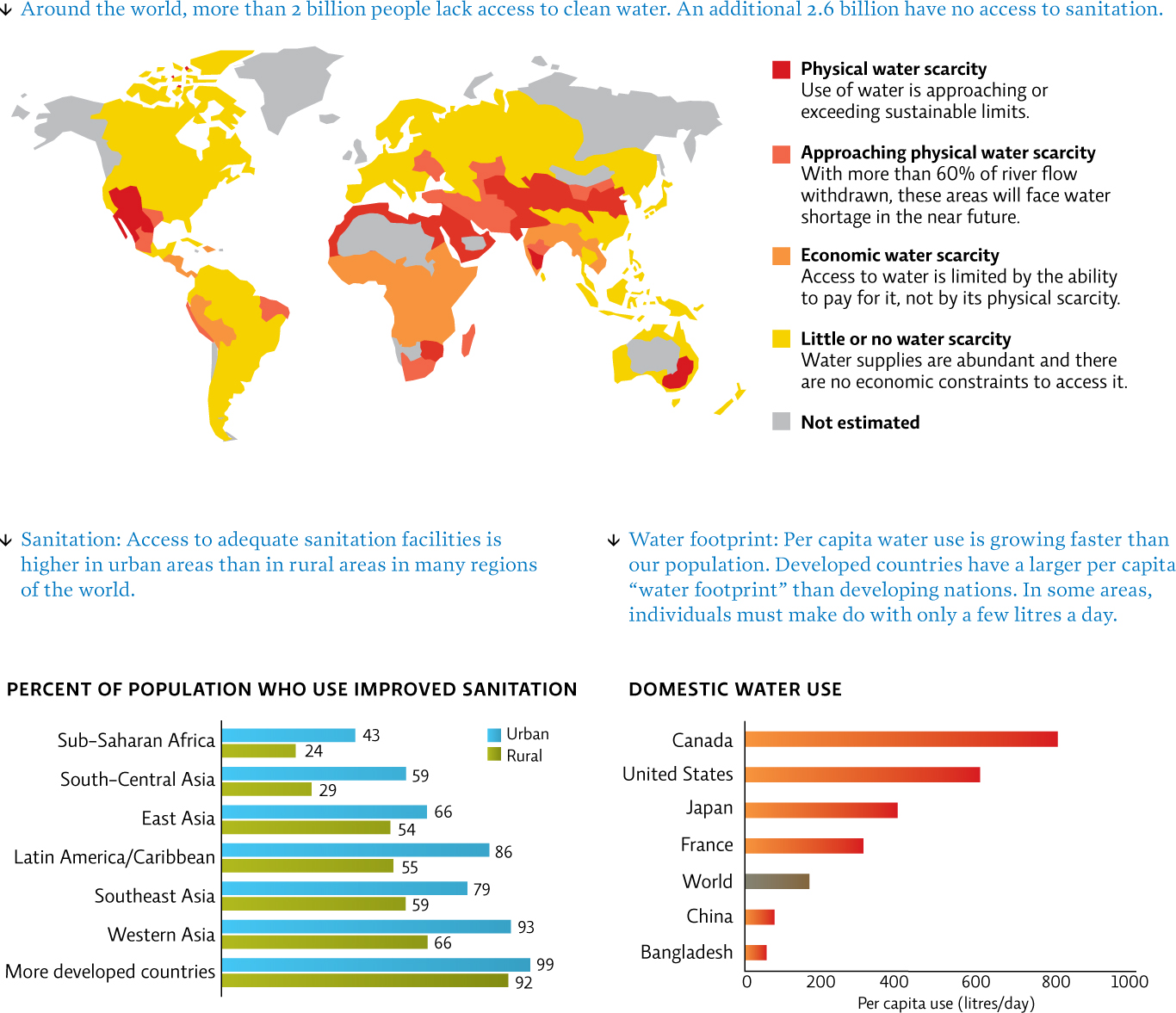

Almost all precipitation ends up falling on the oceans, and a tiny remainder falls on land. This latter portion is the part humans can harvest for their own use. Typically, we draw freshwater from groundwater. But people don’t always live near abundant sources of freshwater, making access a vital issue. Around the world, many areas suffer from water scarcity—not having access to enough clean water supplies. In some dry regions, there is simply not enough to meet needs; many arid nations like those of the Middle East, parts of Africa, and much of Australia face water shortages as a way of life. According to the Water Stress Index, compiled by the risk assessment analyst firm Maplecroft, the Middle Eastern nations of Bahrain, Qatar, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia are the most water-stressed countries in the world, with the lowest per capita water availability. In other areas, there is enough water but people do not have the money to purchase it or dig wells to access it. By far, per capita domestic (household) use of water in developed nations is much higher than that of developing nations—Canadians alone use up to 350 litres of water per day. A wealthy nation may even be able to invest in costly technology to access water (like facilities to remove salt from seawater), but poorer nations do not have this luxury. People in remote regions may have to resort to digging deep wells or installing catchment systems to capture rainwater.

265

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 1 in 3 people—more than 2 billion—lack sufficient access to clean water; even more lack access to sufficient sanitation facilities (safe disposal of human waste). In developing nations where water and funding for basic sanitation are scarce, people use nearby surface waters to meet their basic cooking, drinking, and washing needs. These waters can be contaminated with raw sewage, which increases the chance for disease transmission. According to the WHO, more than 1.1 million litres of raw sewage enters the Ganges River of India every minute. In Africa, almost 3000 people die each day from water-borne diseases like cholera and typhoid fever as a result of poor sanitation and contaminated water.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 1 in 3 people—more than 2 billion—lack sufficient access to clean water.

As populations increase, so will scarcity and sanitation issues; according to the United Nations, 2 out of 3 people will face water shortages by 2025. [infographic 15.3]

266