15.3 Like communities around the world, California depends on many sources of water.

Around the world, each region faces its own water challenges. In California, freshwater flows into the northern part of the state when the Sierra Mountain snowpack melts in the spring. But as Earth’s climate changes, the state could lose much of its snowpack. Indeed, in 2009, California’s precipitation was 80% of its average, and the snowpack only 60% of its average size.

Even in a good snowpack year, the state faces major water issues, explains Deshmukh, now working at the West Basin Municipal Water District in Carson, California. Two-thirds of California’s water is located in the northern part of the state, but two-thirds of the state’s residents live in the south, he explains. At the moment, the state ships some of the northern water to the south via pipes and canals, which costs money and uses a great deal of electricity. And if there is an earthquake or other natural disaster, that transport system could be cut off.

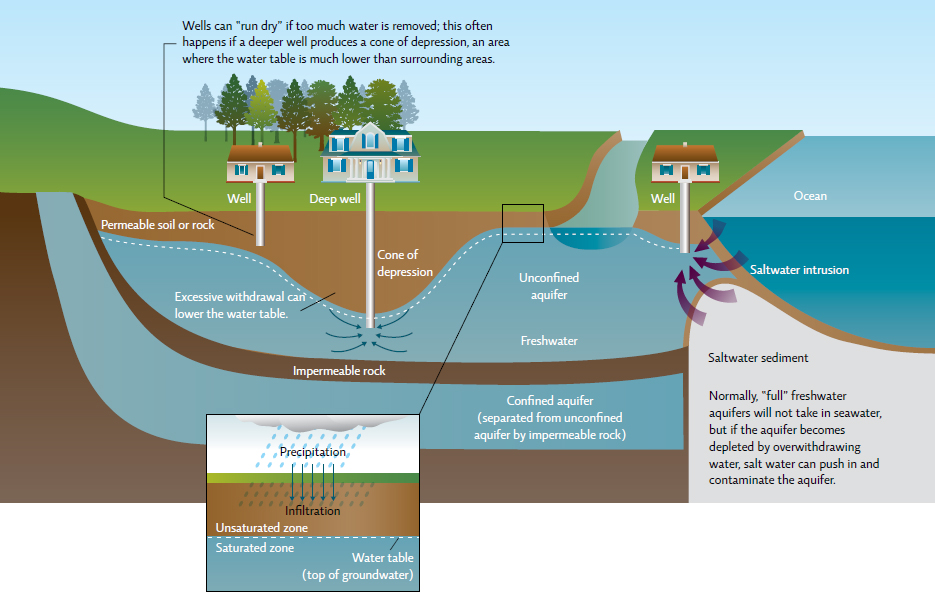

Many people (not just in California) draw their water from an underground region of soil or porous rock saturated with water, called an aquifer. These stores receive water from rainfall and snowmelt that soaks into the ground through infiltration. Plant roots take up some of the water along the way, but much of it continues to move downward, filling every available space in the aquifer. As the water trickles down, it becomes naturally filtered by rocks and soil, which trap bacteria and other contaminants as the water passes by. The top of this water-saturated region, referred to as the water table, rises and falls due to seasonal weather changes.

The depth of Orange County’s groundwater varies, says Deshmukh. At the coast, the aquifer is 6 to 90 metres deep, but further inland, at its deepest, the groundwater extends about 900 metres deep. Water quantity is usually measured in terms of cubic metres. Five hundred cubic metres of water is enough for one Canadian family for 1 year. Deshmukh estimates that over 6 million cubic metres of water is accessible from the deepest part of the aquifer. But that deep subterranean water is harder to get because it costs more to pump it out of the earth than the groundwater closer to the surface.

267

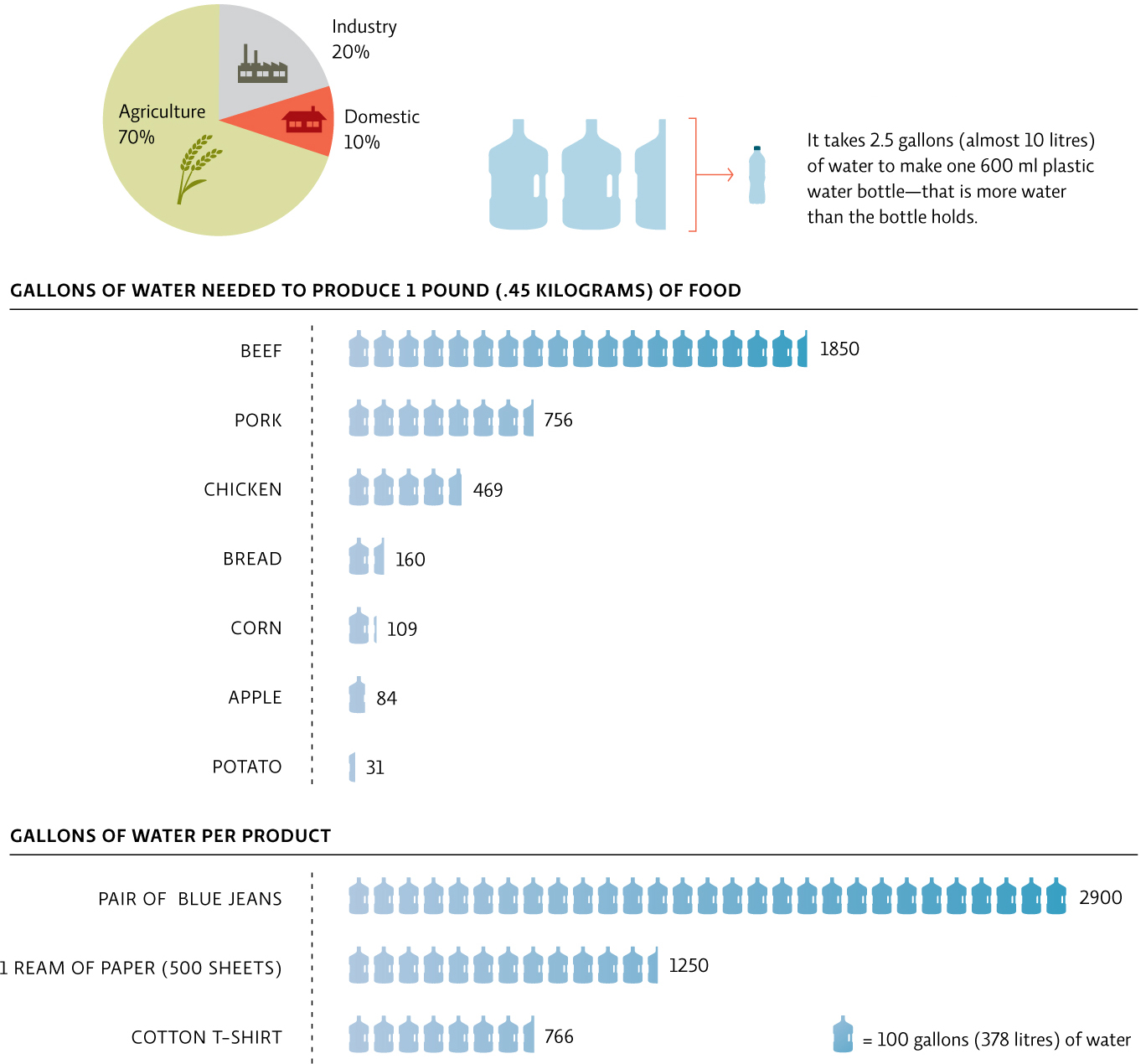

Aquifers remain dependable sources of water only as long as removal rates don’t exceed replenishment rates. The biggest drain on freshwater supplies isn’t the water used to shower, flush the toilet, and wash dishes. While the biggest user of water worldwide is agriculture (at 70%), in Canada, the major user is thermal power generation at 60%; agriculture uses only 9%, mainly due to high precipitation. [infographic 15.4]

In addition, anything that reduces infiltration will reduce the rate at which the aquifer refills and thus decreases the amount of water we can sustainably remove. Infiltration is hampered in urban and suburban settings because of all of the hard surfaces, such as roads and buildings; even the typical suburban lawn is so compacted from the home construction process that very little water infiltrates the ground. Urban and suburban designs that provide ways for water to soak into the ground—such as permeable pavement and rain gardens—can help refill aquifers as well as help to prevent flooding events after heavy rainfalls. (For more on rain gardens, see Chapter 16.)

268

Of course, Californians are lucky enough to have plenty of water all along the coast. But removing salt and other minerals from salt water—a process known as desalination—is expensive and uses a large amount of energy. Still, there are thousands of desalination plants worldwide operating today that meet some of the water needs of their regions. The largest such facilities in the world are in the Middle East, some of which are processing more than 750 million litres of water per day—about 10 times the volume of the largest U.S. plants (which are in Tampa Bay, Florida, and El Paso, Texas).

But in California, the proximity to salt water has actually threatened the freshwater supply.

Decades ago, Orange County officials discovered to their dismay that salt water was seeping into some of the region’s aquifers, putting those precious freshwater stores in jeopardy. Groundwater levels are typically higher than sea level, so salt water doesn’t infiltrate aquifers. But as freshwater was pumped out of the county’s aquifer inland, the groundwater level dropped, and salty ocean water had started to enter the coastal edge of the aquifer to the west, where it bordered the Pacific. In Orange County, some aquifers are confined by geologic faults, which prevent ocean water from entering at some points—but not everywhere. It was in these unconfined coastal aquifers that saltwater intrusion was becoming a problem. [infographic 15.5]

269

To stem the influx of salt water, in 1975 the Orange County Water District started pumping highly treated (purified) sewage wastewater into saltwater-infiltrated wells. At almost 20 million litres a day, the underground injection created a curtain of freshwater along the California coast that prevented salty ocean water from seeping into the county’s aquifer. This water management program was the first to take treated wastewater and pump it into the ground, says Deshmukh.

Most residents had no idea this was going on—even those who thought about water every day. Jack Skinner is a medical doctor and lifelong surfer based in Orange County, whose house in Newport Beach is supplied with water from the county’s wells. His second home is in Laguna Beach, surrounded by water; in the morning, he and his wife would watch from their oceanview apartment as the sun would light up a pole stationed about 1.6 km offshore, marking the spot where a nearby sewer treatment plant discharged its effluent. “Every morning when we got up, we would see that marker.” In the early 1980s, he began experiencing eye infections while distance swimming along the coast. He decided to learn more about the impact of releasing wastewater into the ocean, and how the wastewater was being treated.

Sewage can carry pathogens like viruses and disease-causing bacteria, and surfers get exposed to these when they surf in sewage outflow that is untreated. Public health officials monitor drinking and recreational waters for the presence of coliform bacteria. Since many coliforms are intestinal bacteria, their presence could indicate fecal contamination of the water.

As a doctor specializing in internal medicine and cardiology, Skinner was also concerned about potential health problems that could come with exposure over a long period of time to some chemical contaminants that are carried in drinking water. In California, the water sometimes carries traces of toxic chemicals. In the 1990s, officials detected two toxic chemicals: N-Nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA), created by chemical reactions during wastewater treatment with chlorine; and 1,4-dioxane, which came from a computer circuit board manufacturer releasing industrial wastewater into the sewer system.

270

Over the years, Skinner had become a self-proclaimed “troublemaker,” making sure that wastewater was highly treated before being discharged into the Pacific Ocean, and speaking publicly about water pollution.

One day, the Orange County Sanitation District (OCSD) called Skinner and asked him to come in for a meeting. They wanted to consult with him about a massive new project that they were undertaking that would need the support of the community to succeed. What they said made Skinner very concerned.