16.2 When pollutants infiltrate water bodies, things go awry.

Most of the problems facing Lake Erie can be traced back to water pollution—the addition of anything that might degrade water quality. The list of potential pollutants is discouragingly long. Industrial chemicals and raw sewage get dumped directly into water bodies. Garbage, oil, pesticides, fertilizers, and sediments wash into water with runoff. Contaminants, such as mercury, sulphur, and other air pollutants from fossil fuel combustion, enter lakes with rainwater. While some types of pollutants are more difficult to address, some can be reduced more easily or even ultimately eliminated.

Water pollution is a major concern for Canada, because it is home to 7% of the entire world’s supply of renewable freshwater. The Great Lakes alone supply drinking water to 8.5 million Canadians.

It’s a resource that cannot be taken for granted. In the late 1960s, Harvey Shear spent his summers as an undergraduate student working for professors at the University of Toronto campus in Scarborough, and during breaks he would wander to one of his favourite spots, a creek in the nearby woods. On many days, his reverie would be ruined by the sight of toilet paper and waste bobbing along the running water, which led right into Lake Ontario. “I thought, ‘this is ridiculous,’” says Shear, now a professor at the U of T. “This is one small creek—how much more of this was going on?”

281

282

By that time, sanitation plants and companies had been dumping raw sewage and chemicals into the Great Lakes for years. Tons of unused fertilizers washed off from farm fields into the lake with rainwater. In the 1960s and 1970s, thick layers of floating petrochemicals would start fires on the water’s surface. Massive algal blooms were seen from Lake Superior to the outflow of the St. Lawrence River. Lake Erie was declared “dead.”

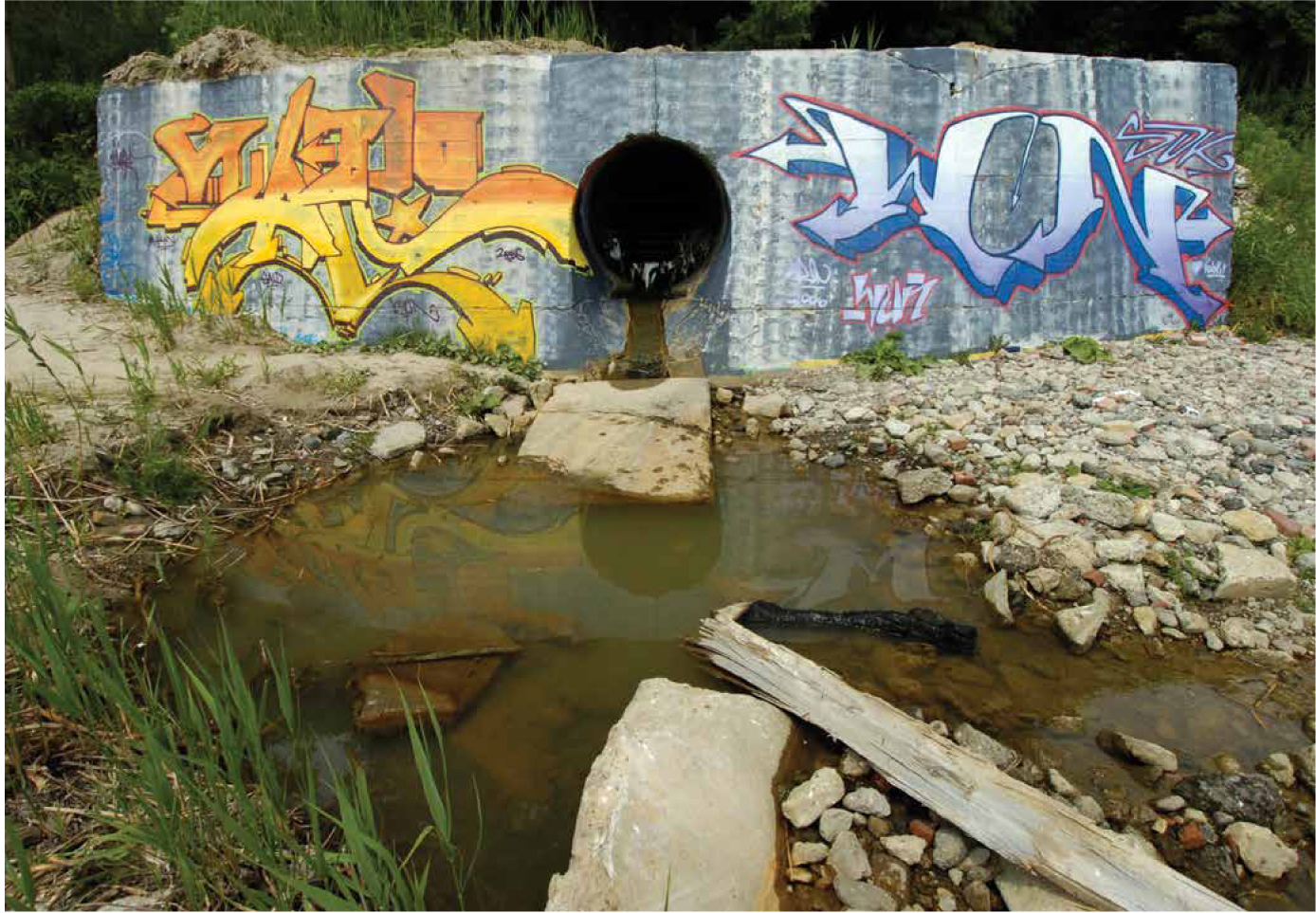

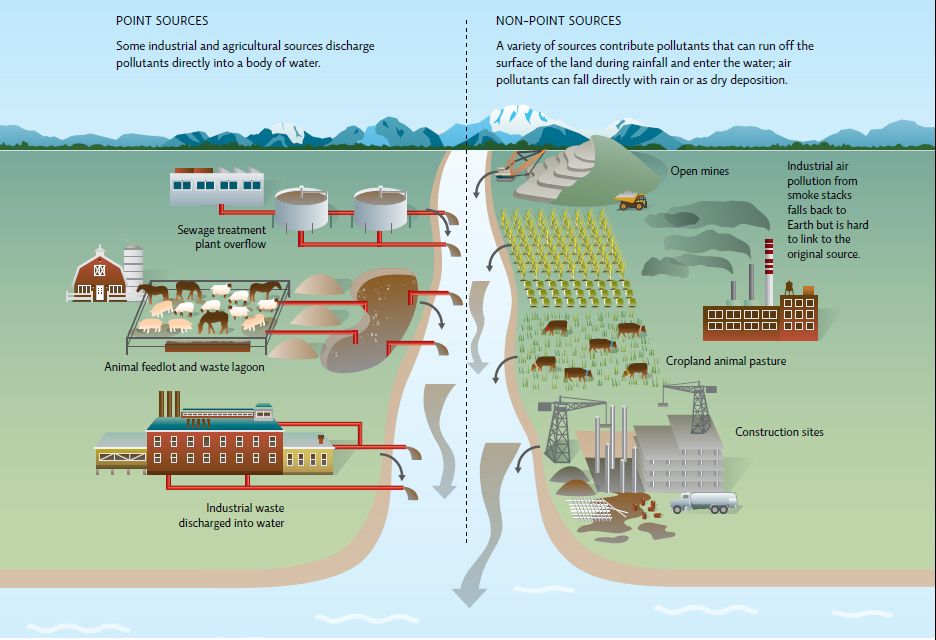

Once experts began looking for the sources of pollution, they found specific entry points, such as oil from an oil spill, or pipes emptying raw sewage or industry discharge into the Great Lakes. This is known as point source pollution, meaning that it can be traced back to discrete sources, which can carry toxic compounds, acids, or pathogens into the water. In contrast, stormwater runoff that makes its way into surface waters is known as non-point source pollution, because there is no single discharge point. For example, this type of pollution carries fertilizer from farms, golf courses, and lawns to the lake and its tributaries (rivers and streams that empty into the lake). [infographic 16.1]

283

In the 1960s and 1970s, Lake Erie was being inundated with high loads of phosphorus, most of it coming from sewage (raw and treated) discharge, an example of point source pollution. Stormwater runoff was also an increasing contributor of nutrients and other chemicals, as more land surfaces that used to absorb water got paved over. These impermeable landscapes are more likely to be sources of problematic substances, such as fertilizers, pesticides, gasoline, antifreeze, pet waste, and motor oil. Five million metric tons of road salt are scattered across icy roads in Canada every year, making salt a major contaminant in waters close to treated roadways. Runoff water can also pick up soil and cause sediment pollution, the most common type of water pollution. Sediments can cloud the water, decrease photosynthesis, clog fish gills, and cover rocky stream beds with a thick coating of mud.

Other types of non-point source water pollution come from industry or vehicle air pollution, which enters surface water via precipitation or dry particle fallout. Lands adjacent to large rivers and lakes have always been preferred sites for industry and cities; more than 360 industrial chemicals have been found in the waters of the Great Lakes, including PCBs, dioxins, and pesticides such as DDT. Fossil fuel combustion also releases sulphur and nitrogen pollution, which can lead to acid rain and lake acidification (although the Great Lakes, because of their size and the fact that they contain minerals such as calcium carbonate that can neutralize acids, can buffer the effects of acid rain more easily than smaller lakes or bodies of water with less of these minerals).

Canada and other high-latitude areas face an additional issue—an accumulation of toxic compounds such as pesticides and heavy metals that are transported in the upper atmosphere to the polar region, where they enter ecosystems (and food chains) as particles that fall to the ground. (See Chapter 21 for more on long-range air pollution.)

284