17.2 Waste is a uniquely human invention, generated by uniquely human activities.

In natural ecosystems, there is no such thing as waste. Matter expelled by one organism is taken up by another organism and used again. This natural recycling is consistent with the law of conservation of matter, which states that matter is never created or destroyed; it only changes form. Forms of matter that are dangerous to living things (think arsenic and mercury) tend to stay buried, deep underground, and are released only during extreme events like volcanic eruptions.

300

Human ecosystems are another story. By taking matter out of the reach of organisms that can use it, we continually disrupt this natural cycle. We do this by converting usable matter into synthetic chemicals that can’t easily be broken down, and by burying readily degradable things in places and under conditions where natural processes can’t run their course.

For example, paper and cardboard break down easily in a compost bin, thanks to the microbes that feed on them. But we typically keep this type of waste in landfills, where the lack of water, oxygen, and microbes forces it to decompose much more slowly than it otherwise might.

Thus matter—the physical substance of which the universe is made—becomes waste—a uniquely human term used to describe all the things we throw away. Waste that can be broken down by microbes is considered biodegradable. Waste that can be broken down by chemical and physical reactions is considered degradable, even if that degradation takes a long time. Some waste—mostly synthetic molecules like the pesticide DDT and CFCs once found in aerosols—is considered nondegradable.

These molecules are chemically stable and don’t degrade in normal atmospheric conditions. And because they haven’t been around for very long, no organism has yet developed (through mutation or genetic recombination) the enzymes to use them as food.

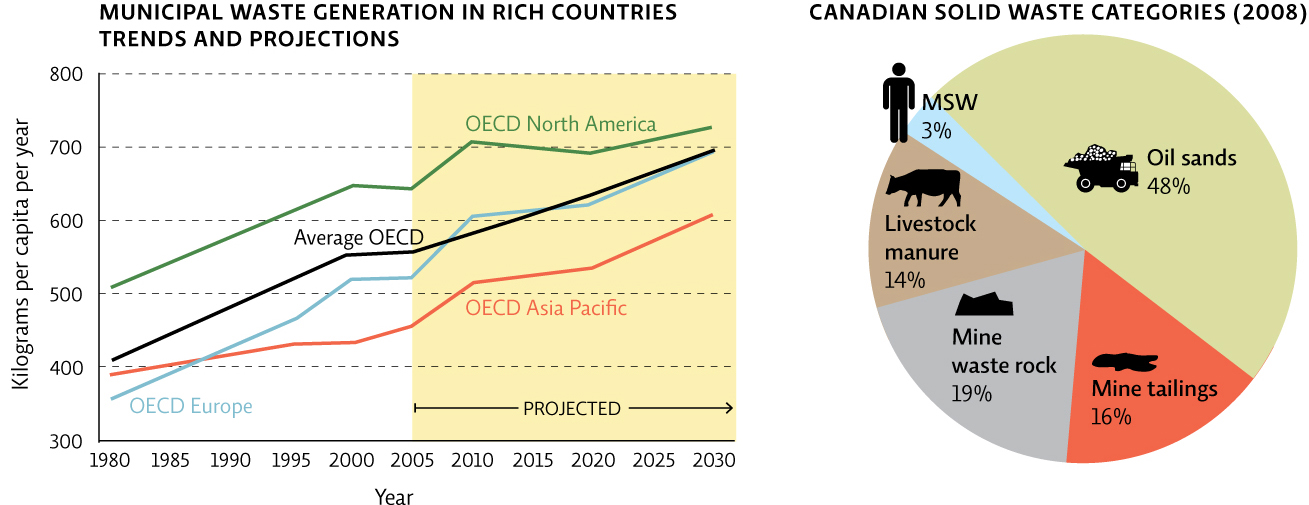

Almost any human activity you can think of generates some form of waste. The harvesting of coal, oil, and ores produces mining waste, which can pollute air, water, and soil, and makes up 83% of solid waste in Canada. Processes that produce food, consumer goods, and industrial products generate agricultural and industrial waste; in Canada, livestock manure waste alone accounts for 14% of solid waste. In built-up municipal areas, the increasingly complicated act of living, working, and producing goods generates its own steady stream of trash. This mix of residential, business, and industrial activity produces what is called municipal solid waste (MSW), or at the community level, an MSW stream. [infographic 17.1]

In Canada, MSW streams make up just 3% of total waste, but this is still a lot of trash: 34 million metric tons annually. In 2008 alone, each Canadian produced about 777 kilograms of solid waste (2.13 kilograms per day), up from about 769 kilograms per capita in 2002 (2.1 kilograms per day). With more than 35 million people living in Canada, this adds up to over 27 billion kilograms (27 million metric tons) of household trash per year. That’s twice the per capita amount produced by the European Union and as much as 10 times the amount produced by most developing countries.

301

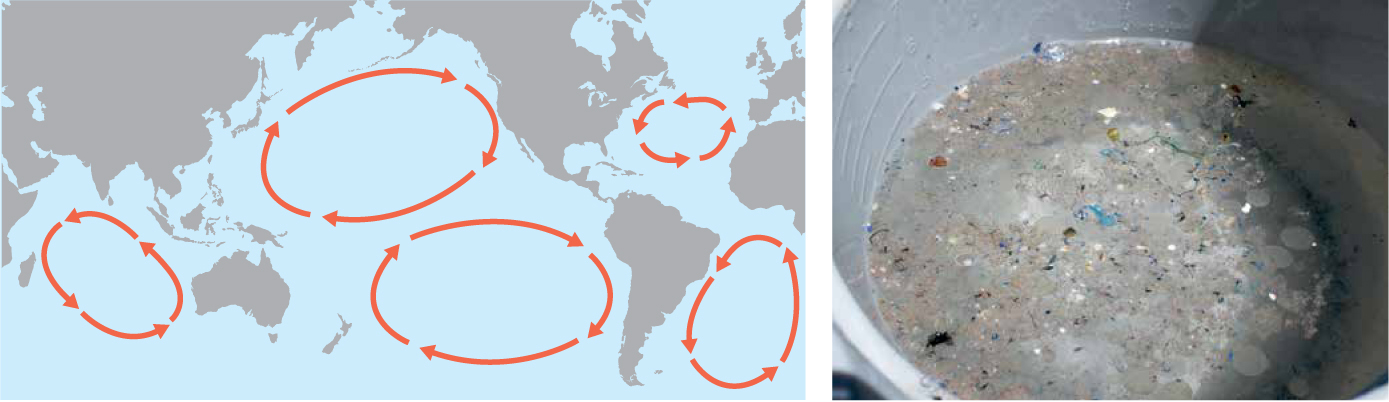

The vast majority of this garbage comes from a familiar array of goods: paper, wood, glass, rubber, leather, textiles, and of course plastic—cheap enough to have become a staple of both advanced and developing societies, light enough to float, and durable enough to persist for hundreds of thousands of years across thousands of kilometres of ocean.