17.8 Consumers have a role to play, too.

Advertising—a virtual staple of advanced societies— bombards us from every corner of modern life: not just on the televisions in our living rooms, but on digital monitors in waiting rooms and food courts, billboards in bus shelters, and the pop-up ads that invade our laptops. The message is surprisingly uniform: to live a happy, more fulfilling life, we simply must have more “stuff.” A good deal of that stuff—though certainly not all of it—is made of plastic. “Plastics are incredibly useful and have made possible many of the greatest breakthroughs in technology and standard of living,” Proskurowski says. “But they have also made our lives lazier. We now buy a bottle of water rather than refill a canteen. We buy individually wrapped bags of mini carrots, instead of buying carrots that are straight from the ground and have to be washed. There are countless other examples, and as we learn with every net tow, there are significant costs to the planet for those choices.”

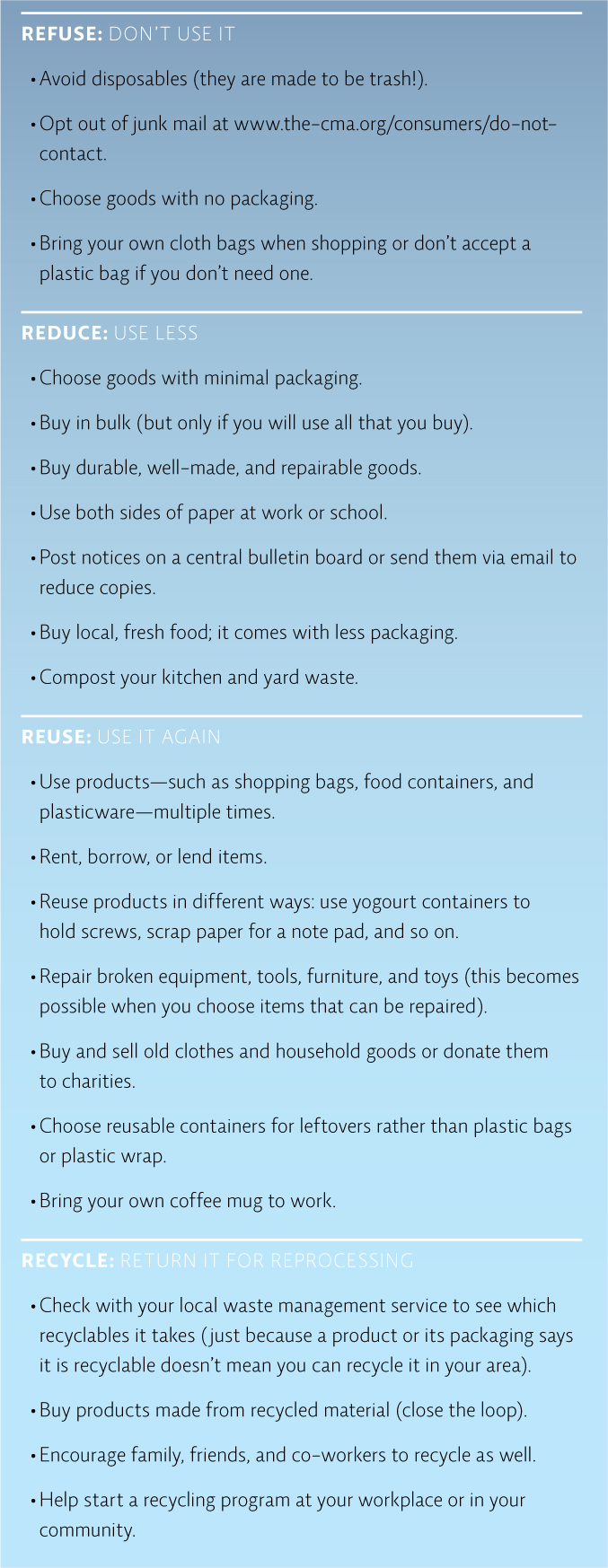

So how do we start making different choices? As any good environmentalist will tell you, it comes down to the “4 Rs”: refuse, reduce, reuse, recycle.

The first thing we can do is simply refuse to use things that we don’t really need, especially if they are harmful to the environment. This may be as minor as declining to take a plastic bag for a few items purchased at the drugstore or as major as biking or walking to work rather than taking the car. The logic is simple: when we save a resource by refusing to use it, that resource lasts longer, which in turn means that less pollution will be generated disposing of it and producing replacements, and more will be available for future uses. “Refusal doesn’t mean never using the resource,” says David Bruno, founder of the 100 Thing Challenge, a popular movement to pare down our worldy possession to 100 items or fewer. “It just means using it at a more sustainable rate.”

If we can’t completely refuse a given commodity, we can still try to reduce our consumption of it, or minimize our overall ecological footprint by making careful purchases. People who must drive to work can minimize their fossil fuel consumption by choosing a more fuel-efficient vehicle. Those who cannot drink tap water might purchase a specialized faucet or pitcher filter instead of relying on bottled water. And all consumers can greatly reduce the amount of waste they generate by paying special attention to packaging. Canada’s EPR Program includes a Sustainable Packaging Strategy; however, this plan is industry-driven, which makes consumer choices an important component in compelling producers and retailers to reduce packaging waste.

And if we can’t avoid using a product, our next best choice is to reuse—the third “R”—something consumers can do with just a little effort, by choosing durable products over disposable ones. “Products produced for limited use are really just made to be trash,” Bruno says. “They pull resources out of the environment and produce pollution at every step of production, shipping, and disposal.” He advises considering use and reuse each time we head to the store; whether you are purchasing clothing, razors, cups, or plates, ask yourself: How long will this last and for what other purpose might it be used?

310

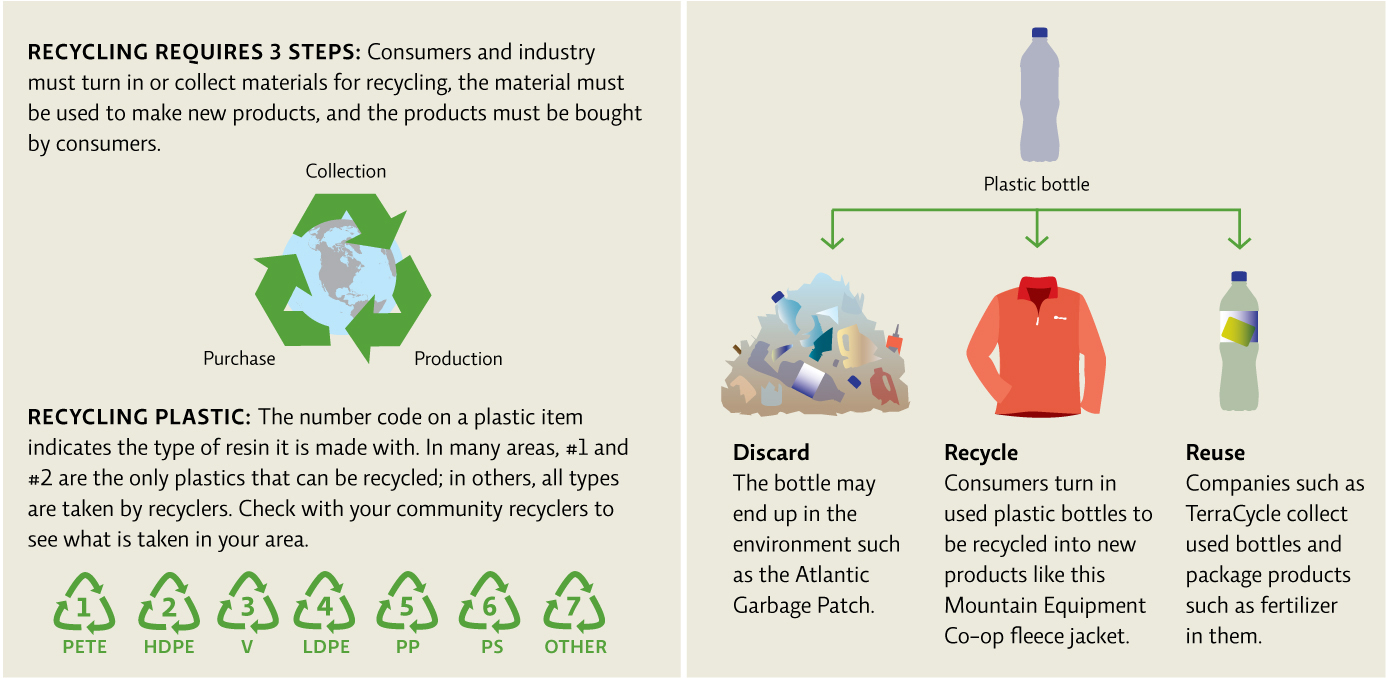

Reusing also applies to industry. TerraCycle is a U.S. company that produces worm compost fertilizer and packages it in used pop and water bottles. The company also collects hard-to-recycle packaging like chocolate bar wrappers and juice pouches and turns them into new products like backpacks.

Once we’ve refused, reduced, and/or reused a given commodity as much as possible, we are left with the final R, recycling, the reprocessing of waste into new products. Recycling has several advantages. By reclaiming raw materials from an item that we can no longer use, we limit the amount of raw materials that must be harvested, mined, or cut down to make new items. In most cases, this helps conserve limited resources, not only trees and precious metals, but also energy. To execute this step properly, we must first have purchased items that can be recycled. We must also close the loop by purchasing items that are made of recycled materials to encourage manufacturers to make products from recycled materials. [infographic 17.8]

Of course, even recycling comes with trade-offs. For example, while less energy and water is used making paper from paper than is used making paper from trees, there are also energy and environmental costs in collecting used paper, storing it, and shipping it to recycling plants. Once these costs are factored in, sustainably harvesting a forest of fast-growing trees may prove to be more environmentally friendly than recycling used paper. [infographic 17.9]

By journey’s end, the crew of the Corwith Cramer had spent a total of 34 days at sea, travelled more than 7000 kilometres, conducted 128 net tows, and counted 48 571 pieces of plastic along the way. Crew members found the northern and southern boundaries of the Atlantic Patch, at latitudes near Virginia and Cuba, respectively. But despite making it as far as the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, they never found the eastern edge.

As the coast of Bermuda came back into view, on July 12, 2010, Proskurowski wrote his last blog post:

311

It is easy to brush off the topic of plastic pollution in the ocean. It occurs thousands of miles from land, in regions of the planet that are rarely visited by humans, and relatively sparsely populated by marine life. It is also easy to pass off responsibility, to say ‘I recycle,’ or ‘It must come from some other (developing) country,’ or ‘It is all fishing or marine industry waste.’ While there may be kernels of truth in all those arguments, the reality of the situation is that open ocean plastic pollution occurs over incredibly large regions of the Earth, has widely distributed point sources, and—because the oceans connect the whole globe—has far-reaching consequences.

Select references in this chapter:

Law, K. L., et al. 2010. Science, 329 (5996): 1185 – 1188.

Statistics Canada, 2012. Human Activity and the Environment: Waste management in Canada (16-201-X).

Young, L. C., et al. 2009. PLoS ONE, 4: e7623.

BRING IT HOME: PERSONAL CHOICES THAT HELP

How much solid waste you produce is under your control. Reducing your waste not only reduces community costs for waste disposal, it also places less pressure on the resources used to produce consumer goods. It is also easy to do and can save you money.

Individual Steps

Track your trash. Record what you throw out for a week by category and weight. How could you reduce your total trash weight by a quarter? By half?

Track your trash. Record what you throw out for a week by category and weight. How could you reduce your total trash weight by a quarter? By half?

Use the information in Infographic 17.8 to identify five changes you can make to reduce your solid waste.

Use the information in Infographic 17.8 to identify five changes you can make to reduce your solid waste.

Consider a semester or summer session with SEA (Sea Education Association) to participate in expeditions such as the one described in this chapter. Visit www.sea.edu/.

Consider a semester or summer session with SEA (Sea Education Association) to participate in expeditions such as the one described in this chapter. Visit www.sea.edu/.

Group Action

Start recycling unusual items in your community. TerraCycle is a company that takes items that usually end up in the garbage, like candy wrappers, corks, and chip bags, and recycles them into new products, like purses or backpacks.

Start recycling unusual items in your community. TerraCycle is a company that takes items that usually end up in the garbage, like candy wrappers, corks, and chip bags, and recycles them into new products, like purses or backpacks.

Talk to friends and family about having “no gift” or “low gift” celebrations. Instead of buying lots of presents, treat friends to a dinner or a fun activity. For large families, use a grab bag or draw names and buy for only specific people.

Talk to friends and family about having “no gift” or “low gift” celebrations. Instead of buying lots of presents, treat friends to a dinner or a fun activity. For large families, use a grab bag or draw names and buy for only specific people.

Policy Change

Talk to community leaders to discuss the possibility of starting a community-wide composting program.

Talk to community leaders to discuss the possibility of starting a community-wide composting program.

Research recycling rates of participation in your community. Advocate for recycling education and curbside recycling programs.

Research recycling rates of participation in your community. Advocate for recycling education and curbside recycling programs.

312