18.2 The natural world holds answers to some environmental problems.

Takao Furuno was, by most standards, a very successful industrial rice farmer, with annual yields among the highest in southern Japan. But it was a tough grind. Each year he was forced to put all his earnings back into the next year’s crop—pesticides, herbicides, irrigation, and fertilizer —so that despite his success, he and his family were left with very little for themselves at the end of each season.

In searching for a better way, he turned, as he often did, to his forebears to see what he could learn from their knowledge. He was surprised to discover that they used to keep ducks in their rice paddies. Most rice farmers consider ducks a pest, albeit a slightly cuter one than the azolla. Adult ducks eat rice seeds before they have a chance to grow, and as they forage, trample young seedlings into the mud. This creates open patches of water, which in turn, invite only more ducks. “If you’re not careful, you end up with a big problem pretty quickly,” says Raquel.

320

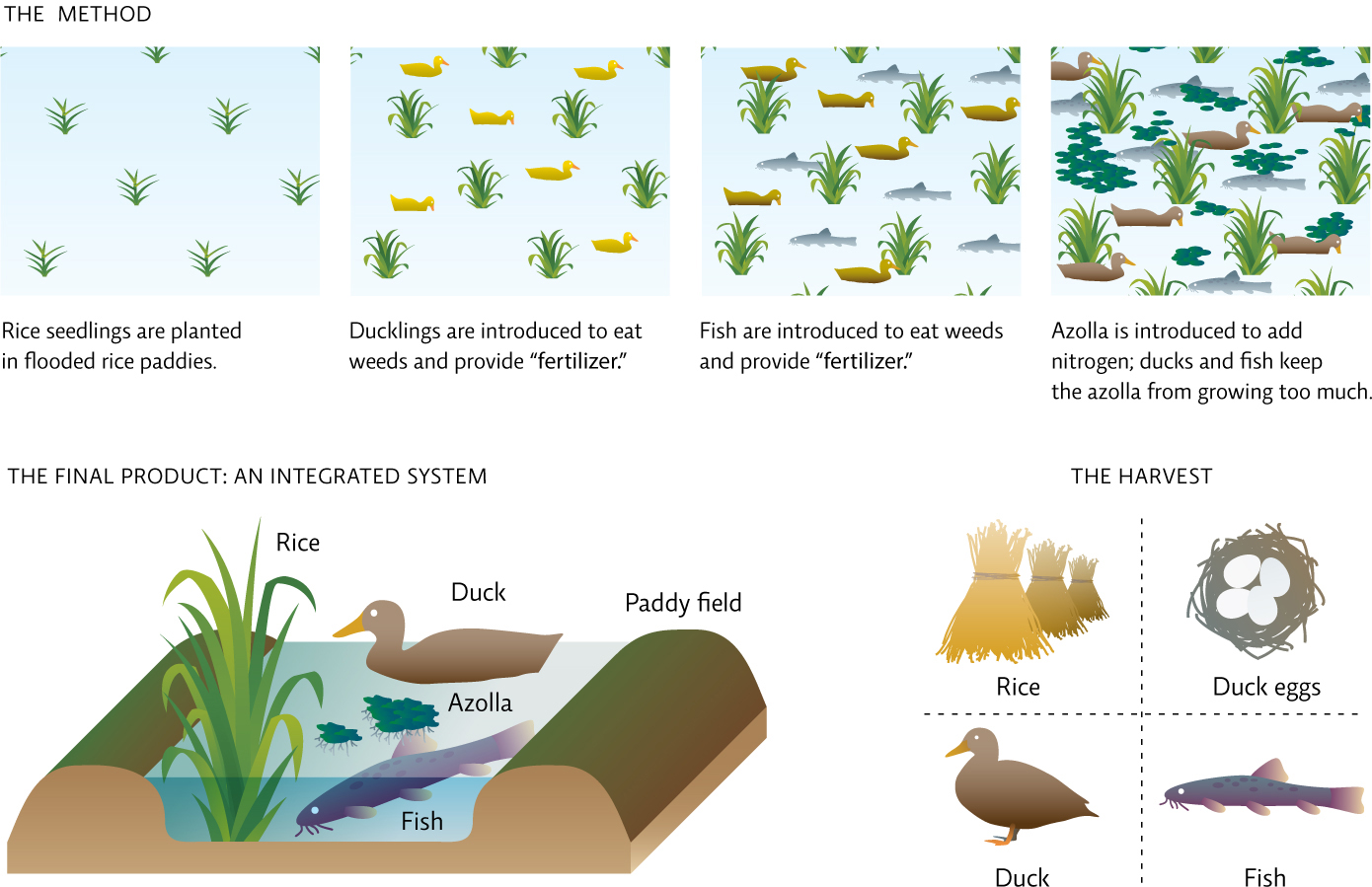

But ducklings, Furuno soon realized, were too small to do such damage; for one thing, their bills were not big or strong enough to extract seeds from mud. Instead, they ate bugs and weeds. Azolla was one of their favourites.

Furuno’s forebears also grew loaches—a type of fish—in their paddies. The loaches would eat azolla and could be harvested and sold as food.

Together, the ducklings and loaches would keep the weed from strangling the rice crop; but they would not completely eliminate the azolla the way a heavy dose of pesticides would. Furuno quickly discovered that, when kept at this benign concentration, the azolla (which contain symbiotic bacteria that produce a usable form of nitrogen) actually fertilize the rice. In fact, between the nitrogen from the azolla, and the duck and fish droppings, he soon found that he no longer needed to spend money on synthetic fertilizer.

There were other financial gains, too. Duck eggs, duck meat, and fish all fetched a good price in the market. And because he was no longer using pesticides, he could also grow fruit on the edges of his rice field. (He opted for fig trees, a crop he could harvest yearly without having to replant).

When raising ducks, fish, and rice crops together, Furuno discovered the root crowns (where the root meets the stem) of rice plants increased to about twice the size that they had been in his old industrial system. A larger root crown meant more rice. “We’re not exactly sure why the crowns grew,” Furuno told an audience of American farmers at a recent convention in Iowa. “But the ducks seem to actually change the way the rice grows. It’s got something to do with the synergy of the whole system.” [infographic 18.3]

321

In the decade and a half since Furuno began duck/rice farming, his rice yields have increased by 20-50%, making his among the most productive farms in the world, nearly twice those of conventional farmers. Independent researchers have verified his results, including the Bangladesh Rice Research Institute which recommends the technique to Bangladeshi farmers. And by now, some 10 000 Japanese farmers have followed his lead; the Furuno method is also catching on in China, the Philippines…and California.