19.1 In the rubble, the true costs of coal

| CHAPTER 19 | COAL |

BRINGING DOWN THE MOUNTAIN

332

333

CORE MESSAGE

Human society runs on energy, and coal continues to be a major reliable energy resource. However, coal mining causes irreversible environmental degradation and the by-products of mining and burning coal pose significant health risks. Despite these drawbacks and the availability of renewable, cleaner energy sources, coal’s availability and industrial presence keep it a major energy player. Researchers are developing ways to lessen the impact of burning coal, but as long as we continue to use it, the impact of mining will remain.

GUIDING QUESTIONS

After reading this chapter, you should be able to answer the following questions:

How important is coal as an energy source and how is it used to generate electricity?

How important is coal as an energy source and how is it used to generate electricity? What is coal, how is it formed, and what regions of the world have coal deposits that are accessible?

What is coal, how is it formed, and what regions of the world have coal deposits that are accessible? What methods are used to mine coal and what are the advantages and disadvantages of each?

What methods are used to mine coal and what are the advantages and disadvantages of each? What are the advantages and drawbacks of burning coal?

What are the advantages and drawbacks of burning coal? What new technologies allow us to mine and burn coal with fewer environmental and health problems?

What new technologies allow us to mine and burn coal with fewer environmental and health problems?

334

About 300 metres above the foothills of Central Appalachia, near the Kentucky–West Virginia border, a four-seater plane ducks and sways like a tiny boat on an anxious sea. It’s windier than expected, and Chuck Nelson, a retired coal miner seated next to the pilot, grips the door in an effort to steady his nerves. The passengers have come to survey the devastation wrought by mountaintop removal—a form of surface mining that involves blasting off up to 120 metres of mountaintop, dumping the rubble into adjacent valleys, and harvesting the thin ribbons of coal beneath.

At first, the landscape looks mostly unbroken; mountains made soft and round by eons of erosion roll and dip and rise in every direction, carrying a dense hardwood forest with them to the horizon. But before long, a series of mountaintop removal sites come into view. Trucks and heavy equipment crawl like insects across what looks like an apocalyptic moonscape: decapitated peaks and hectares of barren sandstone and shale. Smoke curls up from a brush fire as the side of an existing mountain is cleared for demolition. Orange-and-turquoise-coloured sediment ponds—designed to filter out heavy metal contaminants before they permeate the water downstream—dot the perimeter.

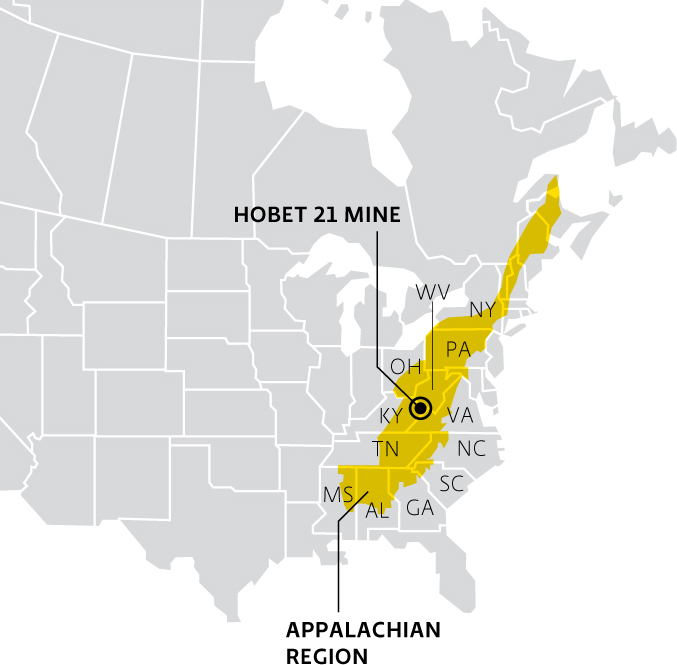

Here and there, a tiny patch of forest clings to some improbably preserved ridge line. “That’s where I live,” Nelson says, forgetting his air sickness long enough to point out one such patch. “My God, you would never know it was this bad from the ground.” The aerial tour has reached Hobet 21, which, at more than 52 square kilometres, is the region’s largest mining operation. So far, sites like this one have claimed more than 400 000 hectares of forested mountain, across just four states: Kentucky, West Virginia, Virginia, and Tennessee. But there is still more coal to mine. And if the coal companies have their way, tens of thousands of hectares more will be thus obliterated in the coming years.

335

To stem this tide of destruction, environmental activists have sued the coal industry, the state of West Virginia, and the federal government itself. They argue that mountaintop removal mining destroys biodiversity, pollutes the water beyond recompense, and threatens the health and safety of area residents. And by obliterating the mountains, they say, it also obliterates the culture of Appalachia.

Coal industry reps have countered by decrying the loss of jobs, tax revenue, and business the already impoverished region would suffer if the mines were to close under the weight of too much regulation. They also point out that the culture of Appalachia is as bound to coal mining as it is to the mountains. Both sides count area residents, including miners, among their ranks.

WHERE IS APPALACHIA?

At the heart of the issue is coal itself—the country’s dirtiest, and most abundant, energy source—the one most responsible for rising CO2 levels from electricity production, but also the one the world relies on most heavily and the one that is being consumed most rapidly. As the Appalachian reserves dwindle, debates raging throughout the decimated foothills are reverberating across an energy-addicted nation.