19.3 Coal forms over millions of years.

The Appalachian Mountains were born a few million years before the rise of the dinosaurs, when Greenland, Europe, and North America hovered near the equator as a single giant landmass bathed in a dense tropical swamp. The northwestern bulge of what is now Africa (see Infographic 19.3) pressed into the easternmost edge of North America, pulverizing the colliding continental margins and forcing a colossal mass of land upward, into a mountain range as high as the Himalayas. It was the last and greatest of three violent clashes that joined all the world’s land into a single supercontinent, upon which stegosauruses and velociraptors would eventually roam.

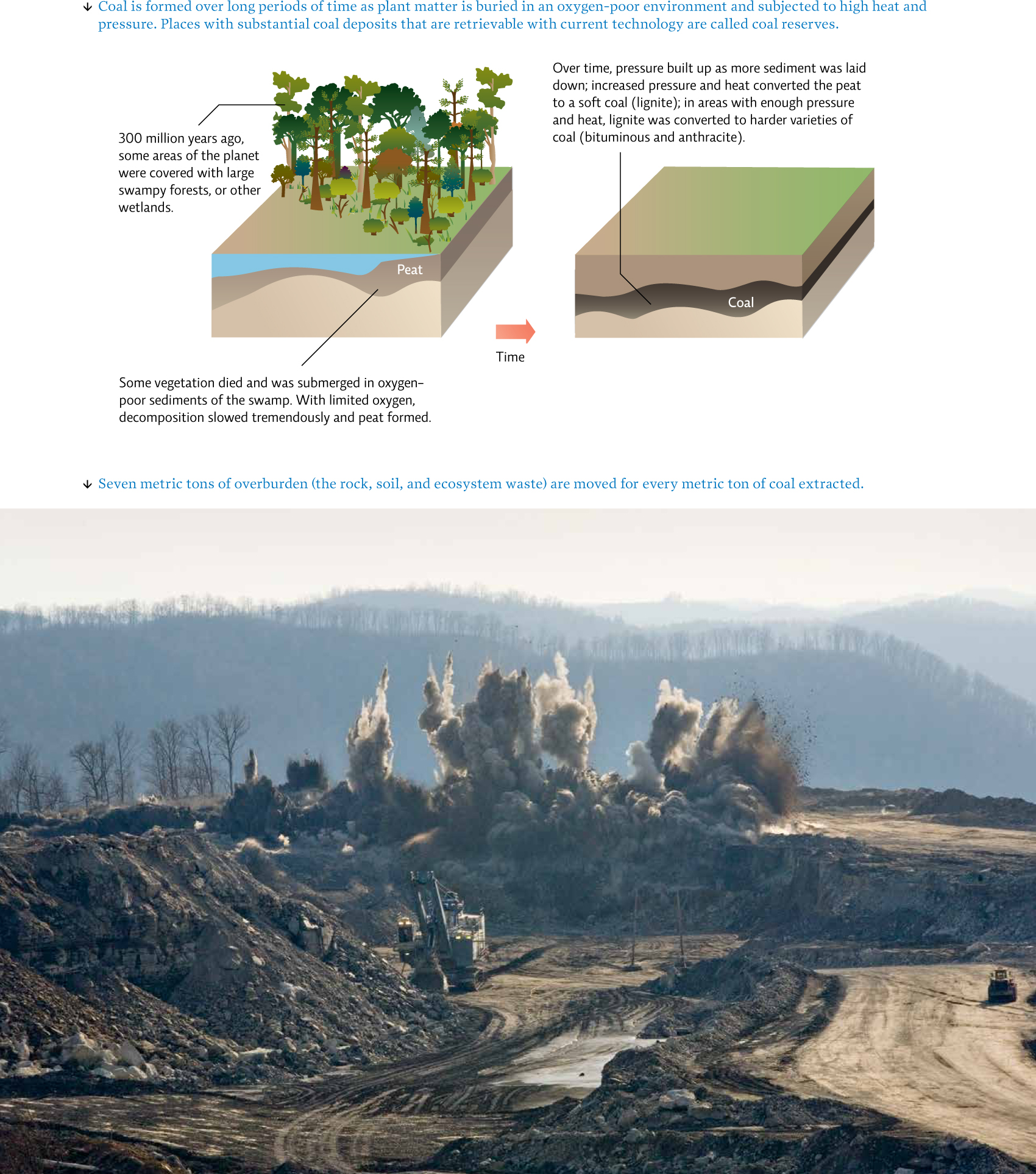

The fallout from this cataclysm—the gradual accretion of decomposing swamp vegetation compressed and baked by heat and time—established the Appalachian coal beds. As the swamp plants died out, they were buried under a mud so thick it kept oxygen out. Instead of being fully decomposed by bacteria, their remains produced peat—a soft mash of partially decayed vegetation. As time passed, and more and more layers of sediment were laid down over the peat, pressure and heat compressed it into the denser rocklike material that we know as coal. [infographic 19.2]

338

339

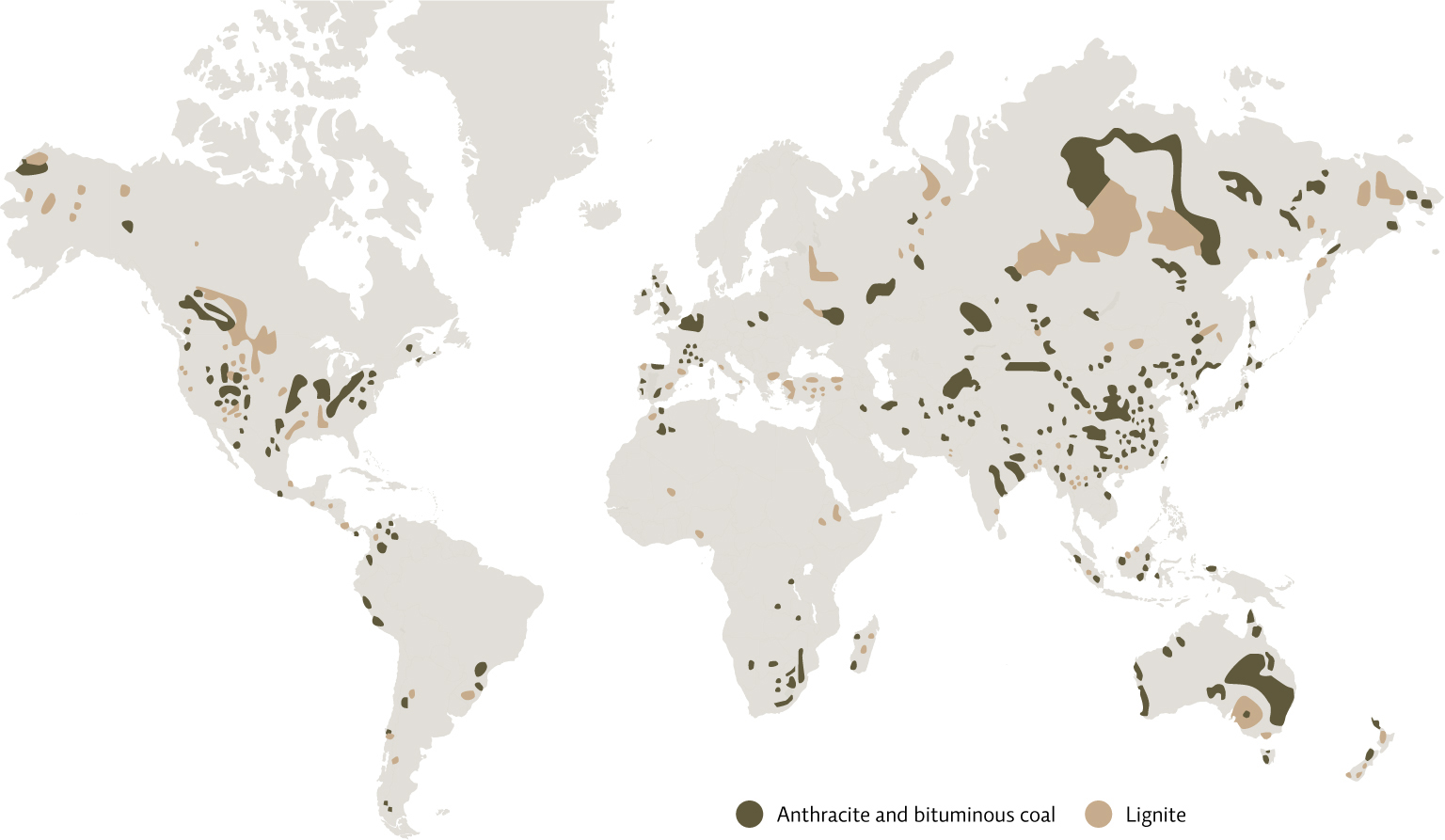

This same story—tectonic upheaval, followed by deep and rapid burying of organic material, followed by the material’s slow compaction into coal—has played out in numerous places across the globe. As a result, coal is found everywhere, though of course, some places have more than others. Europe and Asia hold about 36% of the world’s reserves, while the Asian Pacific has about 30%, and North America holds just over 28%. [infographic 19.3]

The Appalachian beds were once among the most bountiful reserves in the United States; seams as tall as a human adult wound for kilometres through the mountainside and made for easy harvesting. But after 150 or so years of mining, those reserves have dwindled noticeably. At current rates of usage, proven coal reserves (those we know are economically feasible to extract) should last about 120 years—longer if deeper reserves can be accessed. And as the layers of minable coal have grown thinner and harder to reach, the coal industry has become both more sophisticated and more destructive in its approach to extracting the coal.