19.5 Surface mining brings severe environmental impacts.

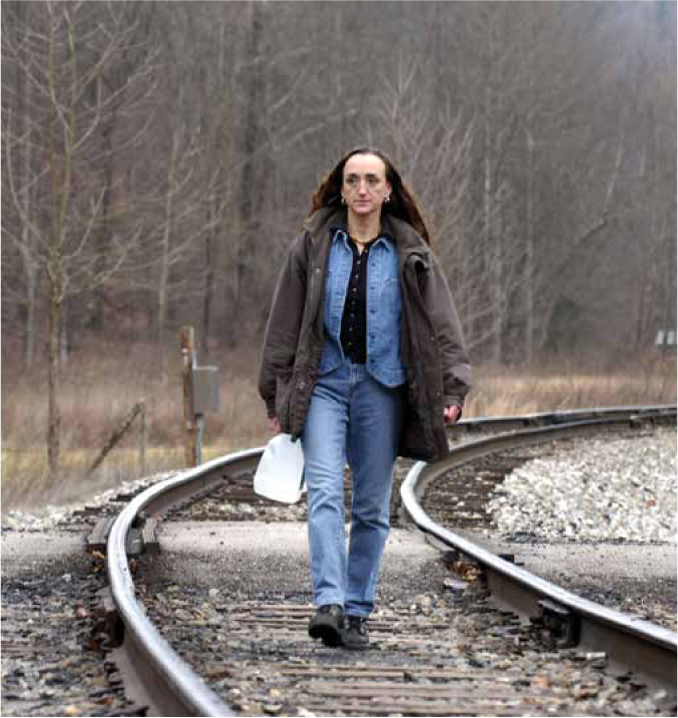

Bob White is a tiny unincorporated village on the edge of Charleston, West Virginia—just one segment of an endless trickle of trailers and shotgun houses that hug the mountain on each side of long winding valley after long winding valley. Maria Gunnoe, a 40-something waitress, and the daughter, sister, wife, niece, and aunt of coal miners, has lived there, on the same property, all her life. She remembers having free run of the mountain as a child. “When we were kids we used to roam deep in the holler,” she says, referring to the mini-valleys that snake through the region’s foothills. “We had access to all the resources—food, medicine, water—that these mountains provided.”

Things are different now. Her own children run into big yellow gates and No Trespassing signs wherever they go. The mountains, she says, have been closed off for blasting. And in the past decade, several million metric tons of overburden—an unimaginable mass—have been dumped into the valleys around Bob White.

The upheaval has had a noticeable impact on area residents. For one thing, the loss of forest and the compaction of so much soil has increased both the frequency and severity of flooding (without trees, and with the soil so compressed, the ground can’t absorb water). “They’ve filled in like 15 of the valleys around me, and floods are about 3 times more serious than they ever were before,” she says. One 2003 flood nearly swallowed her entire valley—house, barn, family and all.

Floods aren’t the only problem. In fact, it’s the blasting that most scares Gunnoe. It fills the air with tiny particles of coal dust—easily inhaled and full of toxic substances like mercury and arsenic. Studies show a higher incidence of respiratory illnesses in mining communities. And according to a 2011 study by Melissa Ahern of Washington State University, children in those communities are more likely to suffer a range of serious birth defects, including heart, lung, and central nervous system disorders. “When they were clearing the ridgeline right behind us, we’d get blasted as much as 3 times a day,” Gunnoe says. “There were days when we’d have to just stay inside because you couldn’t breathe out there. And now, my daughter and I both get nosebleeds all the time.”

In addition to filling the air, these toxic substances also permeate the region’s rivers, streams, and groundwater. In a 2005 environmental impact statement on mountaintop removal mining, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) reported that selenium levels exceed the allowable limits in 87% of streams located downhill from mining operations. Toxic substances were as much as 8 times higher in streams near mined areas than in streams near unmined areas. When tests revealed dangerous levels of selenium in the stream behind Gunnoe’s house, she and her neighbours started getting their water from town. “We can’t trust the water in our own streams anymore,” she says. “It’s sad, but this is just not the same place that I grew up in.”

343

On top of all these immediate threats to human health and safety, area residents like Gunnoe worry about long-term damage to the region’s natural environment. They are not alone. Around the world, in fact, mining operations are a major cause of environmental degradation. To be sure, geological resources—those like copper, gold, iron ore, and coal, that are buried deep underground and so must be dug up—are essential to the functioning of modern society. But harvesting them unleashes a dangerous mix of toxic substances that are normally sequestered away from functioning ecosystems, and that living things—including humans—are not generally well adapted to handle.

“We can’t trust the water in our own streams anymore. It’s sad, but this is just not the same place that I grew up in.” —Maria Gunnoe

At surface mines throughout Appalachia, dangerous quantities of iron, aluminum, selenium, and other metals have leached out from the blasted overburden, and may be starting to bioaccumulate and biomagnify up the food chain. Scientists and fishers alike have noted an alarming decline in certain fish that populate area streams and rivers. And recent surveys indicate that biodiversity has decreased in direct proportion to the concentration of such metals in the water. This loss of aquatic life also affects forest life, since many terrestrial animals feed on insects like mayflies and dragonflies that begin their life in the water.

The nutrient cycle in ecosystems surrounding mined areas has also been altered—in some cases, dramatically. Extra sulphates, released from blasted rock, have increased nitrogen and phosphorus availability, and in so doing have led to eutrophication. And as sulphate levels rise, so do populations of sulphate-feeding bacteria. These microbes transform sulphate into hydrogen sulphide, which is toxic to many aquatic plant species.

Meanwhile, overburden has completely buried more than 3200 kilometres of streams, and destroyed an untold range of natural habitats in the process. And destroying habitats invariably threatens local species diversity. Biodiversity in the streams of Appalachia is rivalled only by that in the streams found in rainforests; the diversity of trees is also second only to the tropics. With these ecosystems destroyed on more than 500 mountains in Appalachia, researchers predict the permanent loss of many local plant and animal species.

344

Slurry impoundments—reservoirs of thick black sludge that accompany each mining operation—are among the most controversial features of the landscape created by mountaintop removal. They too are a consequence of thinner coal seams. “The thinner seams are messier,” says Randal Maggard, a mining supervisor at Argus Energy, a company that has several mining operations throughout Appalachia. “It’s 6 inches of coal, 2 inches of rock, 8 inches of coal, 3 inches of rock, and so on. It takes a lot more work to process coal like that.” To separate the coal from the rock, miners use a mix of water and magnetite powder known as slurry that coal can float in. Once the sulphur and other impurities have been washed out, the coal is sent for further processing, and the slurry by-product is pumped into artificial holding ponds.

Maggard insists the impoundments are safe. “Before we fill it, we have to do all kinds of drilling to test the bedrock around it,” he says. “And then a whole slew of chemical tests on top of that—all to make sure the barrier is impermeable.” Still, area residents worry about a breech. With good reason.

In October 2000, the dike holding back the slurry at one of these ponds failed, pouring more than 1 million kilolitres (30 times the Exxon Valdez spill) of toxic sludge into the Big Sandy River of Martin County, Kentucky. The contamination killed all life in some streams and eventually reached the Ohio River, more than 32 kilometres away. The sludge was 1.5 metres deep in some places. The EPA would register it as one of the worst environmental disasters in the eastern United States’ history. Eleven years later, sludge can still be found a few centimetres under the river sediments.

345