19.7 Reclaiming closed mining sites helps repair the area but can never recreate the original ecosystem.

In some ways, closed mines—those where all the coal has been harvested—look even more alien than active sites like Hobet 21. Instead of the natural sweep of rolling hills, staircase-shaped mounds covered with what looks like lime-green spray paint join one mountain to the next. Atop some of them, gangly young conifers, evenly spaced, strain toward the Sun. The spray paint is really hydroseed, and most of the gangly trees are loblolly pine, a non-native hybrid that foresters are trying to grow in the region.

348

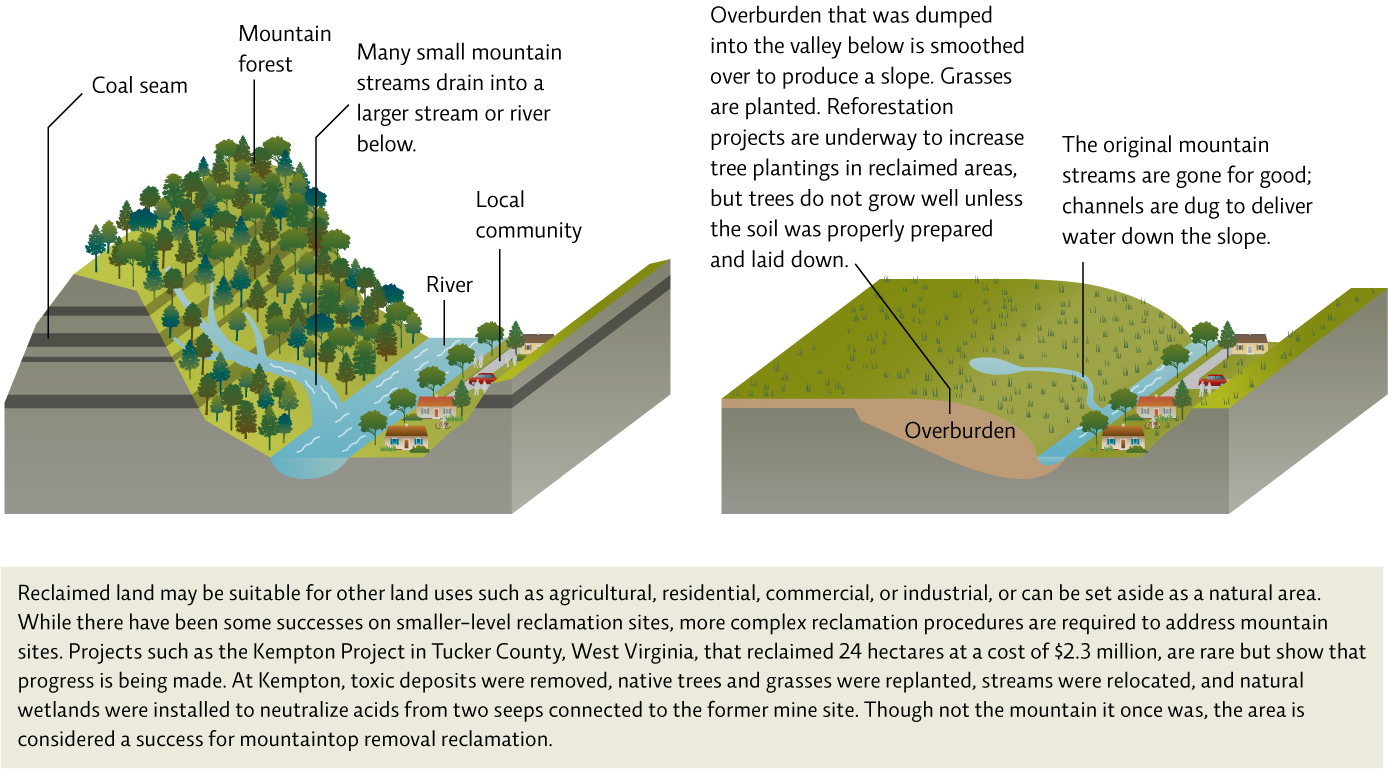

Such efforts represent the coal industry’s attempt to honour the U.S. Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act, which in 1977 mandated that areas that have been surface mined for coal be “reclaimed” once the mine closes. Reclamation requires that the area be returned to a state close to its pre-mining condition.

At some surface mines, at least, reclamation is straightforward (albeit labour-intensive) work: if the mined area was originally fairly flat, the reclamation process includes filling the site with the overburden and contouring the site to match the surrounding land. This relaid rock is then covered with topsoil saved from the original dig. Sometimes, alkaline material such as limestone powder is sprinkled overtop to neutralize acids that have leached into the soil. Vegetation, usually grass, is then planted, leaving other local vegetation to move in on its own. According to the Mineral Information Institute, more than 1 million hectares of coal-mined area have been successfully reclaimed using this strategy.

But reclamation has always been a controversial idea. For one thing, the Appalachian forests were created over eons. In fact, in some ways, they were born of the same calamity that laid the coal beneath the mountains. As the supercontinent drifted, carrying the Appalachian range well north of the equator, a temperate hardwood forest replaced the swamps and grew over time into one of the most biologically diverse ecosystems on the planet. In some areas, a single mountainside may host more tree species than can be found in all of Europe, not to mention songbirds, snails, and salamanders that exist nowhere else on Earth.

For another thing, rebuilding a mountain is considerably more difficult than filling in a strip mine where the original land was relatively flat. Critics say that so far, there’s no evidence that a site as expansive and as thoroughly destroyed as Hobet 21 could ever be truly reclaimed. In one survey, Rutgers ecologist Steven Handel found that trees from neighbouring remnant forests did not readily move in to recolonize mountaintop removal sites, largely because of problems with the soil: at some mines, there was simply not enough of it; at others, it has not been packed densely enough for trees to take root. Those problems have technical solutions, Handel writes, but so far, the seemingly simple act of changing reclamation protocols has been stymied by politics.

349

And trees are just one facet of reclamation. What about all those streams that were buried? The 1973 U.S. Clean Water Act prohibits the discharge of materials that bury a stream or, if unavoidable, requires mitigation practices that return the stream close enough to its original state such that the overall impact on the stream ecosystem is “non-significant.” Both Canada and the United States have federal regulations that require stream restoration. U.S. industry reps argue that they are indeed working to rebuild streams: once the overburden has been reshaped and smoothed over, they dig drainage ditches and line them with stones in a way that resembles a stream or river. But so far, research shows—and most ecologists agree—that such channels don’t perform the ecological functions of a stream. “They may look like streams,” says ecologist Margaret Palmer, from the University of Maryland. “But form is not function. The channels don’t hold water on the same seasonal cycle, or support the same aquatic life, or process contaminants out of the water—all things a natural stream does.” [infographic 19.8]

In Appalachia, the arguments over when and where and how to mine for coal are quickly boiling down to a single intractable question: once it’s all gone, how will we clean up the mess we’ve made? For a story that has played out over geologic time, the question is more immediate than one might think. In West Virginia, coal reserves are expected to last another 50 years, at best. That means no matter what regulations the government imposes, or what methods the coal companies resort to, the day of reckoning will soon be upon us.

Select references in this chapter:

Ahern, M., et al. 2011. Environmental Research, 111: 838–846.

Epstein, P.R., et al. 2011. Annals of The New York Academy Of Sciences: Ecological Economics Review, 1219: 73–98.

Handel, S.N. 2002. EIS Technical Study Project for Terrestrial Studies.

Hendryx, M., and Ahern, M. 2008. American Journal of Public Health, 98: 669–671.

Pond, G., et al. 2008. Journal of the North American Benthological Society. 27: 717–737.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2005. Final Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement on Mountaintop Mining/Valley Fills in Appalachia. Philadelphia, PA: EPA.

Weakland, C.A., and Wood, P.B. 2005. The Auk, 122: 497–508.

BRING IT HOME: PERSONAL CHOICES THAT HELP

Although coal is one of the most abundant fossil fuels, its drawbacks are significant. They include CO2 emissions; the release of air pollutants that cause environmental problems such as acid rain; health problems such as asthma and bronchitis; and massive environmental damage from the mining process. One way to minimize the impact of coal is to reduce consumption of electricity.

Individual Steps

Always conserve energy at home and at the workplace.

Always conserve energy at home and at the workplace.

- Turn off or unplug electronics when not in use.

- Put outside lights on timers or motion detectors so that they only come on when needed.

- Dry clothes outdoors in the sunshine.

- Turn the thermostat up or down a couple of degrees in summer and winter to save energy and money.

Group Action

Organize a movie screening of Coal Country or Kilowatt Ours, which present issues related to coal mining and mountaintop removal from many perspectives.

Organize a movie screening of Coal Country or Kilowatt Ours, which present issues related to coal mining and mountaintop removal from many perspectives.

Policy Change

The Appalachian Regional Reforestation Initiative is a great example of how groups, sometimes with very different objectives, can work toward a common goal. Go to arri.osmre.gov to see how this coalition of the coal industry, citizens, and government agencies are working to restore forest habitat on lands used for coal mining.

The Appalachian Regional Reforestation Initiative is a great example of how groups, sometimes with very different objectives, can work toward a common goal. Go to arri.osmre.gov to see how this coalition of the coal industry, citizens, and government agencies are working to restore forest habitat on lands used for coal mining.

Visit http://content.sierraclub.org/coal/ to find out about events in various states and for the opportunity to weigh in on the decommissioning of outdated coal power plants and the building of new ones in the United States.

Visit http://content.sierraclub.org/coal/ to find out about events in various states and for the opportunity to weigh in on the decommissioning of outdated coal power plants and the building of new ones in the United States.

350