1.6 Human societies can become more sustainable.

Unlike their counterparts in Greenland, the Icelandic Vikings responded to their environment and adopted more sustainable practices. They didn’t have to look far for a model of sustainability: natural ecosystems are sustainable. This means they use resources—namely, energy and matter—in a way that ensures that those resources continue to be available.

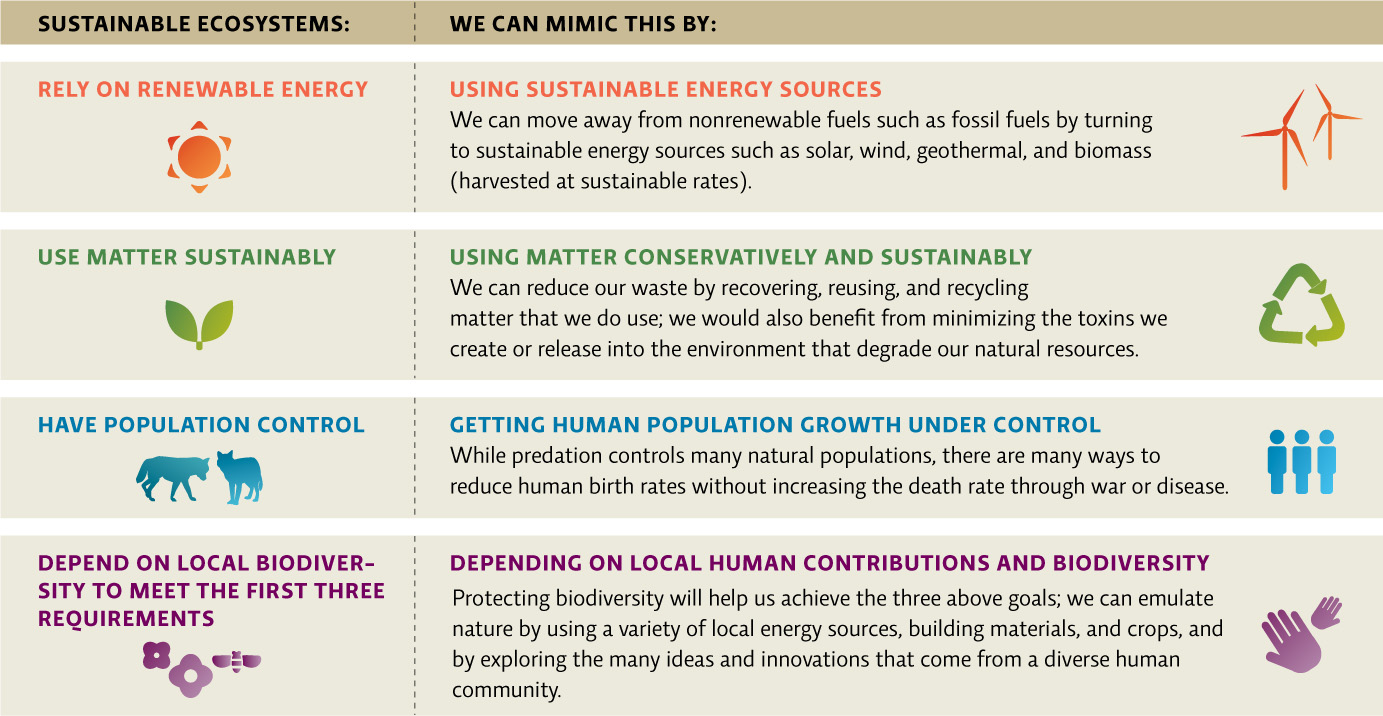

To survive, organisms need a constant, dependable source of energy. But as energy passes from one part of an ecosystem to the next, the usable amount declines; therefore, new inputs of energy are always needed. A sustainable ecosystem is one that makes the most of renewable energy—energy that comes from an infinitely available or easily replenished source. For almost all natural ecosystems, that energy source is the sun. Photosynthetic organisms such as plants trap solar energy and convert it to a form that they can readily use, or that can be passed up the food chain to other organisms.

Unlike energy, matter (anything that has mass and takes up space) can be recycled and reused indefinitely; the key is not using it faster than it is recycled. Naturally sustainable ecosystems waste nothing; they recycle matter so that the waste from one organism ultimately becomes a resource for another. They also keep populations in check so that the resources are not overused and there is enough food, water, and shelter for all.

Lastly, sustainable ecosystems depend on local biodiversity (the variety of species present) to perform many of the jobs just mentioned; different species have different ways of trapping and using energy and matter, the net result of which boosts productivity and efficiency (see Chapter 8). And predators, parasites, and competitors serve as natural population checks.

10

Thus, natural ecosystems live within their means and each organism contributes to the ecosytem’s overall function. This is not to imply that natural ecosystems are perfect places of total harmony, but those that are sustainable meet all four of these characteristics.

Human ecosystems are another story. Humans tend to rely on nonrenewable resources—those whose supply is finite or is not replenished in a timely fashion. The most obvious example of this is our reliance on fossil fuels such as coal, natural gas, and petroleum, culled from deep within Earth, to power our society. Fossil fuels are replenished only over vast geologic time—far too slowly to keep pace with our rampant consumption of them. On top of that, we have a hard time keeping our population under control, despite (or maybe because of) all the advances of modern technology. We also generate volumes of waste, much of it toxic, and have yet to fully master the art of recycling.

Increasingly, however, we humans are looking to nature to help us learn how to change our ways. In Janine Benyus’ book Biomimicry (the term used to describe the strategy of mimicking nature), Benyus explains that biomimicry involves using nature as a model, mentor, and measure for our own systems. Emulating nature (nature as model) gives us an example of what to do; it can also teach us how to do it (nature as mentor) and the level of response that is appropriate (nature as measure). As we’ll see in later chapters, scientists are using biomimicry to design more sustainable methods of growing crops and livestock for human consumption, and of trapping and using energy. [infographic 1.5]

Despite such efforts, many critics say that modern global societies are not acting nearly as quickly as they could or should. Once again, the charge echoes those archaeologists have levelled at the Vikings of Greenland. To understand what prevents us from changing our ways even in the face of brewing calamity, it helps to understand why the Greenland Vikings failed to do the same.