20.1 A massive oil reserve in Alberta raises concerns over the cost of our dependence on fossil fuels

| CHAPTER 20 | OIL AND NATURAL GAS |

SANDS OF TIME

352

353

CORE MESSAGE

We depend on nonrenewable fossil fuels (coal, oil, and natural gas) for a range of products, not just to fuel our cars or heat our homes. Our dependence on fossil fuels has led us to become increasingly destructive and extreme in our quest to extract them from the environment.

GUIDING QUESTIONS

After reading this chapter, you should be able to answer the following questions:

How are fossil fuels like oil and natural gas formed and why are they considered nonrenewable resources?

How are fossil fuels like oil and natural gas formed and why are they considered nonrenewable resources? Where are current oil reserves found, and what is meant by “peak oil”?

Where are current oil reserves found, and what is meant by “peak oil”? How is conventional oil extracted? What are some of the environmental consequences of finding, extracting, and using oil?

How is conventional oil extracted? What are some of the environmental consequences of finding, extracting, and using oil? What are the advantages and disadvantages of using natural gas instead of oil?

What are the advantages and disadvantages of using natural gas instead of oil? What unconventional sources of oil exist? What are the benefits of using them? The costs?

What unconventional sources of oil exist? What are the benefits of using them? The costs?

354

Once his favourite thing to do, David Schindler’s fishing trips deep into northern Canada were becoming a source of dread. To get there, he had to fly far out over the Athabasca watershed in central Alberta, an expanse of lush peatlands and forests as far as the eye could see. Starting in the 1970s, however, Schindler began to notice a couple of small pits in the landscape. These were signs industry had begun to tap into the enormous reserves of oil embedded in the soil, known as oil sands. Schindler, an ecologist at the University of Alberta, would peer down at these pits in curiosity, watching companies try to extract the sticky, dense conglomeration of sand or clay that may hold trillions of barrels of oil— the world’s largest oil sands reservoir.

In the mid-1990s, things began to change. The occasional, small excavation pits expanded exponentially, as mining in the area rapidly increased. Once the development started, it didn’t stop, Schindler says, and what were once lush bogs and forests quickly became barren, grey landscapes. “Eventually, it looked like somebody had dropped a bomb there, leaving nothing behind but a crater with little spots for buildings, smokestacks, and pipes.” Monster trucks carrying mined materials churned up the parched soil; every spot with standing water looked like an oil slick. “It was pretty horrifying.” [infographic 20.1]

Schindler had a bird’s-eye view of Canada’s energy boom, the result of rising oil prices, financial incentives to invest in oil sands exploration, and technological improvements that made this untapped reserve extractable. By the late 1990s, multiple companies were building massive facilities to mine the oil sands; by 2006, average annual production from these projects exceeded one million barrels per day. And there’s no end in sight: production in Canada is set to increase, rising from 2.8 million barrels per day in 2010 to 4.7 million barrels per day in 2025, largely due to increased mining from the oil sands. Much of that oil is exported; indeed, Canada is the largest exporter of crude oil to one of the largest energy users in the world, the United States.

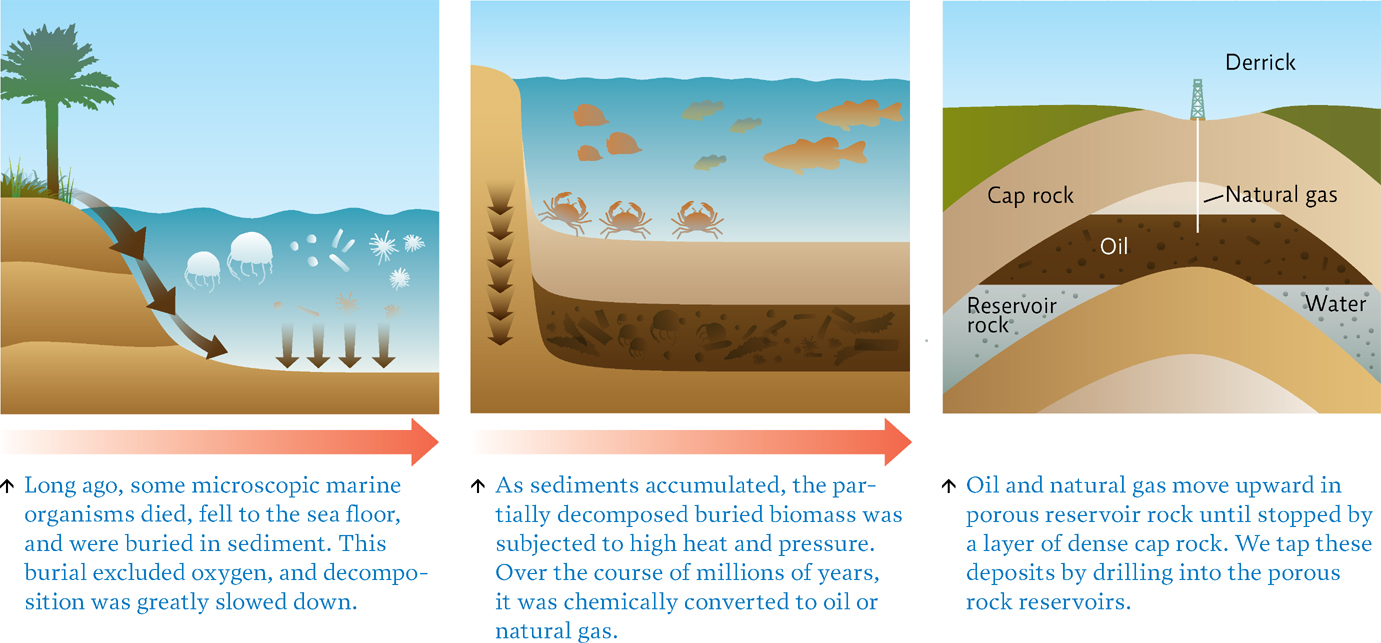

Everywhere, countries are looking for new sources of oil. Oil is one of three principal fossil fuels on our planet, along with coal and natural gas, and we depend heavily on these sources for energy and to make the everyday products we use (for more on coal, see Chapter 19). Fossil fuels form over millions of years when organisms die and are buried in sediment before they can decompose. Over time, as pressure and heat increase, the buried material goes through a chemical transformation into oil, natural gas, or coal.

Even though they are produced by natural processes, fossil fuels are considered nonrenewable because we are quickly using them up in a fraction of the time it takes for them to form. [infographic 20.2]

Over the decades, we have come to depend heavily on fossil fuels, especially oil. But this effort can cause environmental problems—destroying habitats and blanketing entire regions in spilled oil, such as the 2010 Deepwater Horizon explosion that devastated the Gulf of Mexico. This has caused some to openly question whether our unquenchable thirst for oil has gone too far, forcing exploration of new sources of oil such as offshore reserves and oil sands, which are more difficult to extract or process than conventional oil. “Oil sands are the first major commercial foray into these unconventional oils,” says Simon Dyer, policy director at the nonprofit Pembina Institute. “As we’ve finished extracting the easy-to-access oil, technology is unlocking more lower-grade, polluting sources of oil.”

Over the years, as he watched the increase in mining of Alberta’s oil sands unfold below him with each successive trip, Schindler realized that there had to be some effect on the local environment. He and his colleagues have spent more than a decade studying the impact on the Athabasca River, which cuts through mining sites, looking at water quality and its effects on the fish that many local people depend on for food. Nothing prepared them for what they would find.

355

356