20.2 Oil is a valuable resource but it has many drawbacks.

Oil is a liquid fossil fuel made up of hundreds of types of hydrocarbons, organic compounds of hydrogen and carbon. Hydrocarbons take many forms—solid, liquid, or gas—and we have developed methods for extracting them from the depths of Earth. Oil is found some 300 to 9000 metres (0.3-9 kilometres) below the surface, where rigs have to dig deep in order to reach it. Crude oil can be found as tiny droplets wedged within the open spaces, or “pores,” inside rocks, which are so small you’d need a microscope to see them. Since crude oil from this type of deposit can be pumped out by drilling oil wells, it is considered a conventional oil reserve.

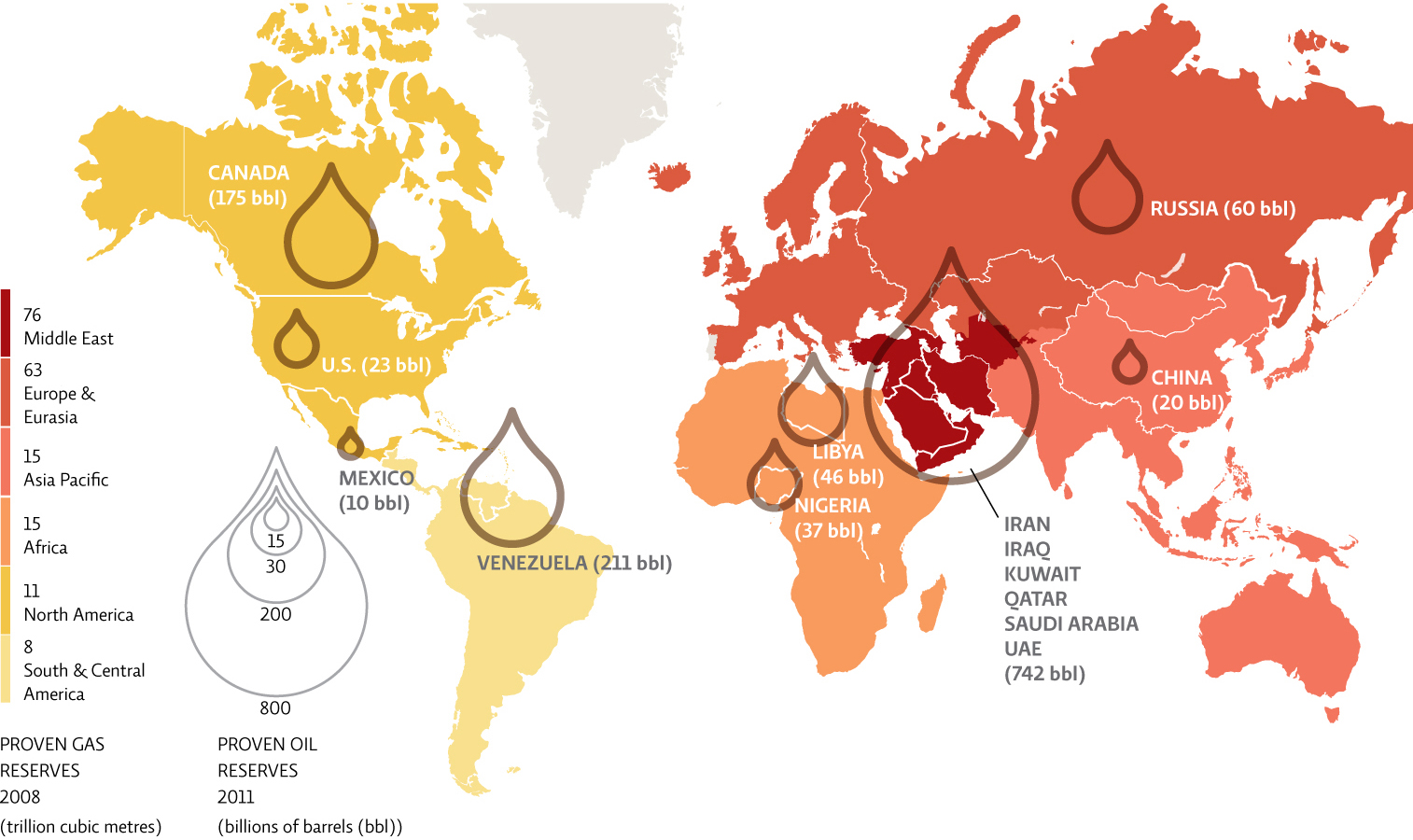

There are different types of crude oil deposits. Canada sits on the third-largest proven reserves of oil in the world (only Saudi Arabia and Venezuela have more), 98% of which consist of oil sands. The oil found in oil sands is known as bitumen, a heavy, black oil that, in these deposits, is blended with sand, clay, and water. This type of heavy oil cannot be recovered using conventional methods, and contains impurities that must be removed before refinement—making oil sands unconventional oil reserves. Such reserves require intensive processing to separate oil from other natural elements.

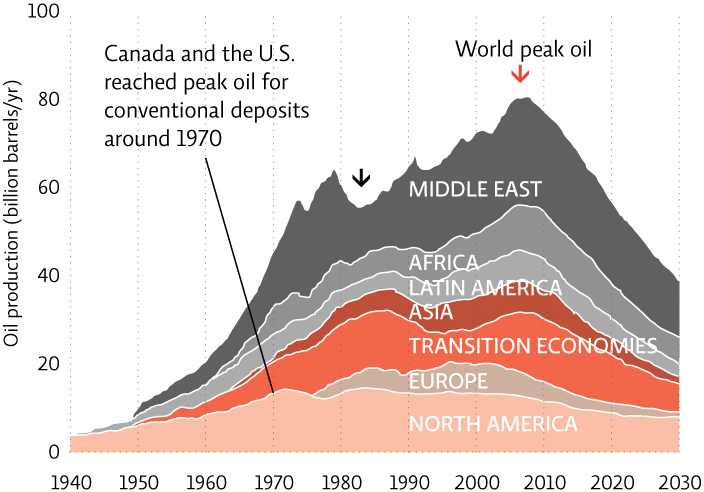

World demand for oil rises more than 2% each year, and it is possible we have already passed peak oil, the moment in time when conventional oil will reach its highest production levels and then steadily and terminally decline. Passing peak oil will have international economic repercussions as the demand for oil outstrips the supply and prices go up. [infographic 20.3]

Proven reserves are the amount of a fuel that is economically feasible to extract from a deposit using current technology. Conventional oil reserves are not evenly distributed around the planet, leading to political problems between countries that have the oil, like those in the Middle East, and those that do not have enough to meet their own needs, like the United States. Even though Canada is a major consumer of fossil fuels, it produces more than it consumes every year. The global distribution problem is compounded by the fact that proven conventional reserves are past peak. At current rates of extraction and use, these proven reserves are expected to last another 40 years (though this number is uncertain because reports of oil reserves tend to be questionable— many nations keep their reserve estimates a secret).

357

Natural gas reserves are also finite. Russia has the largest amounts of natural gas, with about 25% of the world’s conventional reserves; Canada has only 1%, but is the fourth-largest exporter, sending much of it to the United States. Canada itself relies on natural gas for 22% of its energy needs. Total world conventional reserves of natural gas are expected to last 60–100 years at current rates of use. But like oil, natural gas use is increasing at about 2% per year. At this rate, natural gas could run out much sooner than predicted. [infographic 20.4]

But we are nowhere near “peak oil” for oil sands or shale oil (and, as we shall see, for natural gas). As new technologies and higher energy prices make these unconventional oil sources viable alternatives, they have the potential to change the global energy future—at least in the near term.

358