21.2 Outdoor air pollution has been under examination for many years.

As far back as the 1930s, scientists recognized a link between outdoor air pollution and human illness. In 1930, for instance, 63 people died and 1000 were sickened in Belgium when a temperature inversion—a situation that occurs when the temperature is higher in upper regions of the atmosphere than in the lower, causing pollutants to become trapped near Earth’s surface—led to a sudden spike in lower atmospheric sulphur levels. And 1952 was the year of the famous Great Smog in London, UK, when acid aerosols trapped in the lower atmosphere in London killed 4000 people.

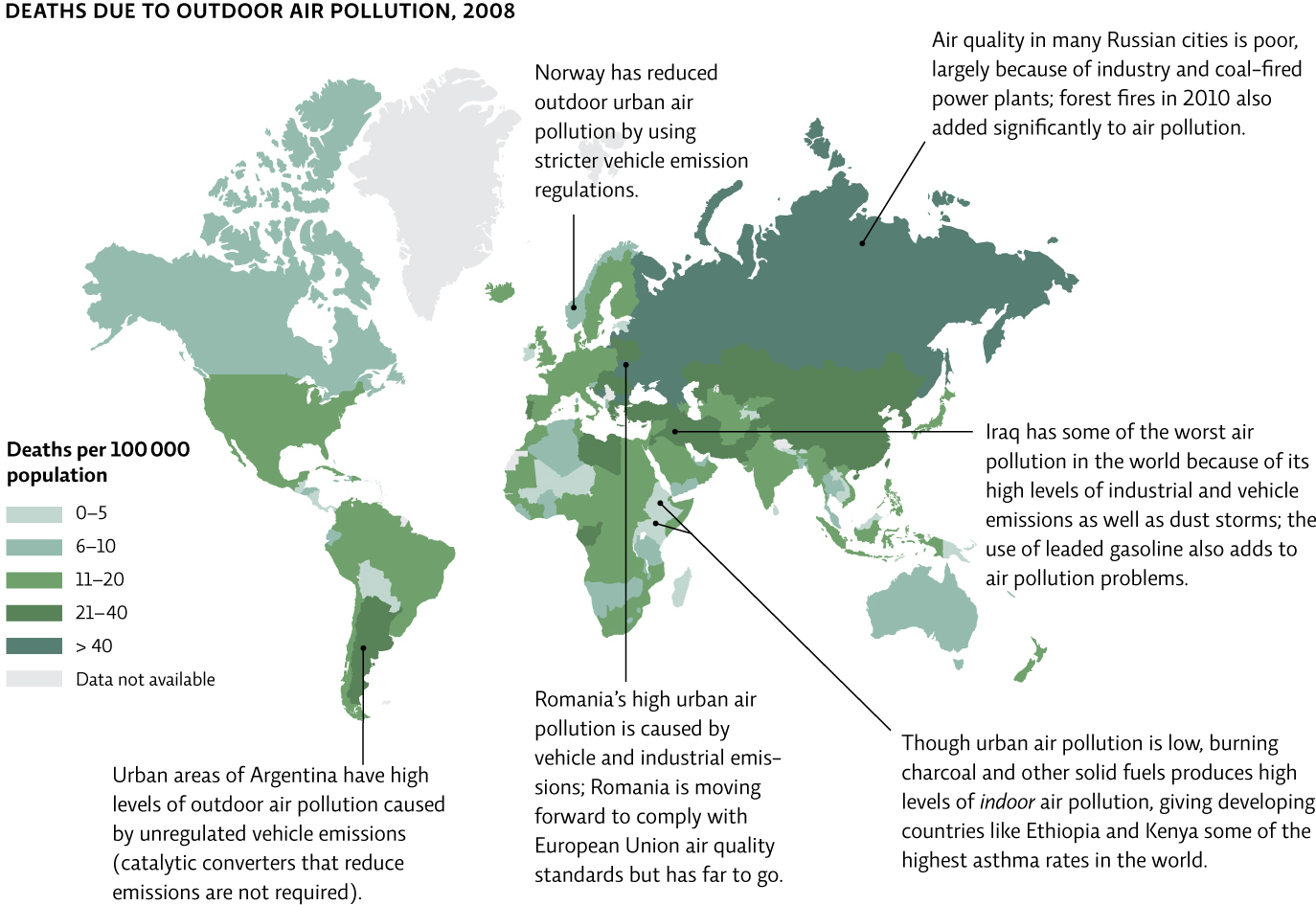

In many urban areas and in developed nations today, much of the air pollution comes from vehicle exhaust and industry emissions, including emissions from coal-fired power plants. While less-developed nations do have outdoor pollution, their biggest problem is often indoor air pollution from small particles released through burning solid fuels such as charcoal, wood, or animal waste. However, only in the last 25 years have scientists really been able to tease out the link between air pollution and asthma. [infographic 21.1]

375

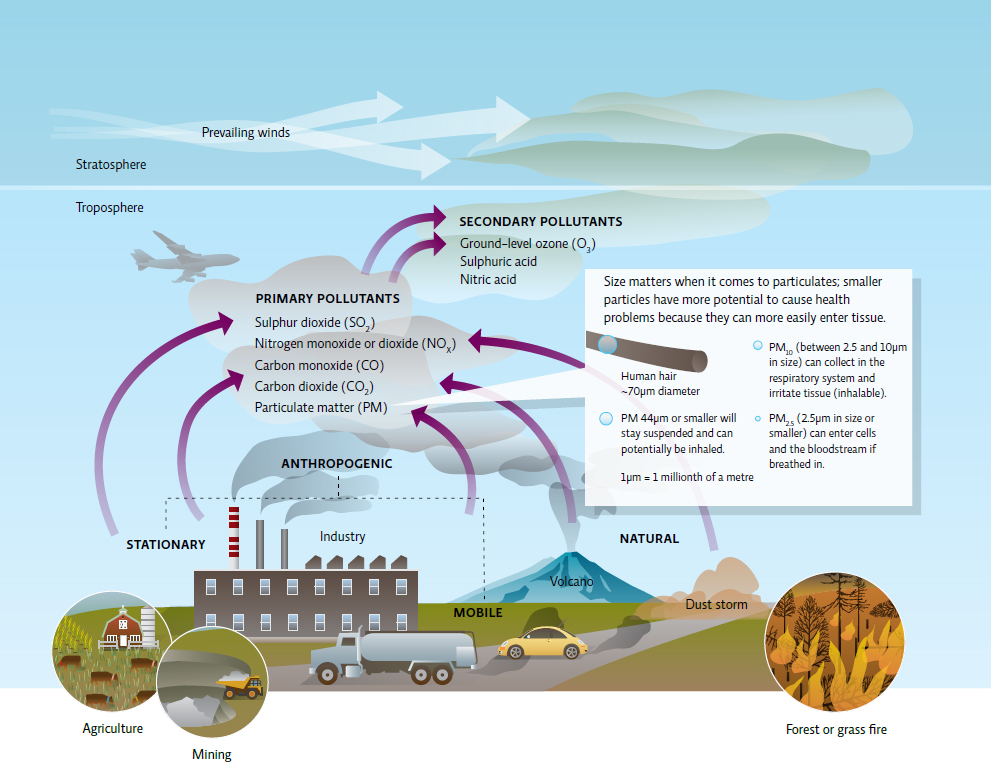

Outdoor air pollution includes chemicals and small particles in the atmosphere that can be either natural in origin—arising from sandstorms, volcanic eruptions, or wildfires—or come from humans, such as pollution released from factories and vehicles during the combustion of fossil fuels, or from burning any biomass such as wood, crop waste, or garbage. Of these anthropogenic sources, primary air pollutants are pollutants released directly from both mobile sources (such as cars) and stationary sources (such as industrial plants). In addition, some primary air pollutants react with one another or with other chemicals in the air to form secondary air pollutants. For example, ground-level ozone forms when some of the pollutants released during fossil fuel combustion react with atmospheric oxygen in the presence of sunlight. Acid rain is another common secondary pollutant.

Pollution can also move from the troposphere up into the stratosphere, a much thinner layer of the atmosphere that extends from 11 to 50 kilometres above Earth. This region contains the “ozone layer,” an area with high ozone (O3) concentrations. As we saw in Chapter 2, ozone in the stratosphere is significant because it serves as Earth’s sunscreen, blocking some of the dangerous ultraviolet (UV) radiation from the sun. Air pollution can have grave impacts on this layer; for instance, chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs)—compounds that contain carbon, chlorine, and fluorine—can travel up into the stratosphere and destroy ozone.

Don’t confuse ground-level ozone with stratospheric ozone depletion. These are two very different problems though they deal with the same molecule—O3. Ozone in the stratosphere is a good thing—but you don’t want to breathe it in as it can directly damage the sensitive tissue of the lungs. Even plants are damaged by the corrosive action of ozone.

376

Outdoor air pollution, in all forms, is one of the most dramatic contributors to asthma. When the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) started regulating pollution back in 1971, the agency did not know the extent to which air pollution could affect health; in fact, the EPA administrator noted at the time that the agency’s clean air regulations were “based on investigations conducted at the outer limits of our capability to measure connections between levels of pollution and effects on man.” Nevertheless, in 1971, the EPA set standards for the most common but problematic pollutants. Five of these were chemical air pollutants: sulphur oxides, carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, ground-level ozone, and lead; standards were also set for particulate matter (PM)— particles or droplets small enough to remain aloft in the air for long periods of time. [infographic 21.2]

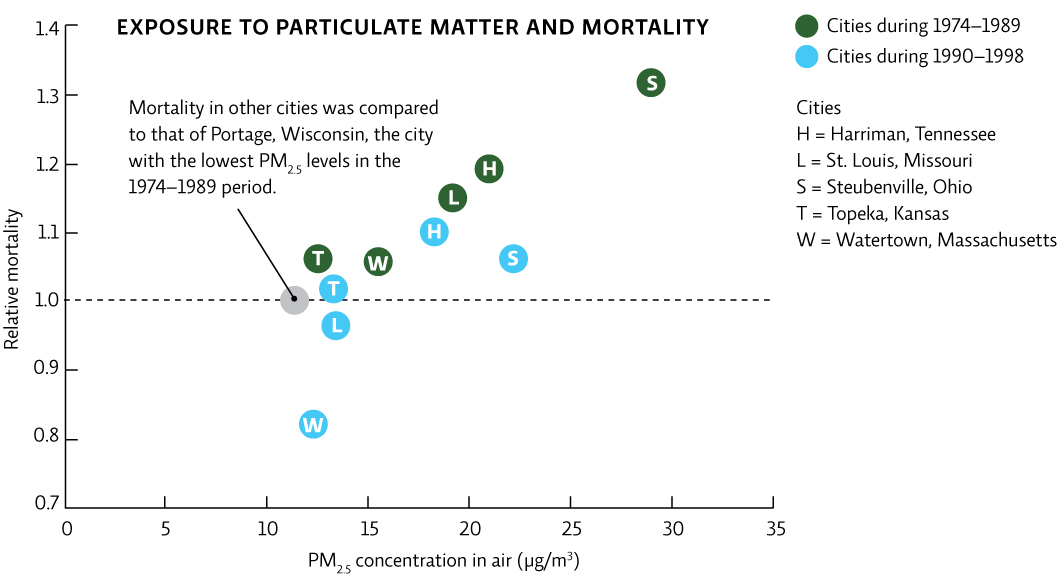

These six “criteria pollutants” are still considered the most problematic and health-threatening pollutants in the United States. A 1993 study published by Harvard University researchers helped establish the link between air pollution and impaired health. A follow-up study estimated that particulate pollution—which includes soot, ash, dust, smoke, pollen, and small, suspended droplets (aerosols)—accounts for 75 000 premature deaths per year in the United States. [infographic 21.3]

377

Although all particulates reduce visibility, it is the smallest particles—those with a diameter less than 2.5 micrometres (µm), about 1/40th the diameter of a human hair—that aggravate asthma and other chronic lung diseases, and increase one’s risk for death.