22.5 Current climate change has both human and natural causes.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is an international scientific body, established by the United Nations and the World Meteorological Organization in 1988, that is made up of thousands of scientists from around the world. They evaluate all the climate science that is published through peer review and compile it into a cohesive series of publications that explain what is understood about the current state of the climate; they also make recommendations that may inform government action.

404

Here’s what everyone agrees on so far: Earth’s atmosphere is changing dramatically and with alarming speed. Analysis of CO2 trapped in ice cores reveals that current levels are higher than at any time in the last 800 000 years and are increasing steadily. In 2011, the atmospheric concentration of CO2 was 390 ppm (parts per million). This is considerably higher than the preindustrial level of about 280 ppm—a level that had been maintained for millennia.

The majority of this change is due to human activities, especially the burning of fossil fuels, and the consequent release of greenhouse gases like CO2 into the atmosphere. For most of modern history, the United States has been the biggest emitter of CO2. In 2007, however, China took the lead: the proliferation of coal-fired power plants that has fuelled the country’s recent economic and industrial growth has also released copious amounts of CO2 into the atmosphere. China now releases nearly 30% more CO2 than the United States (though the United States still releases more per person than any other country in the world, and much of the CO2 released in the 20th century came from U.S. sources).

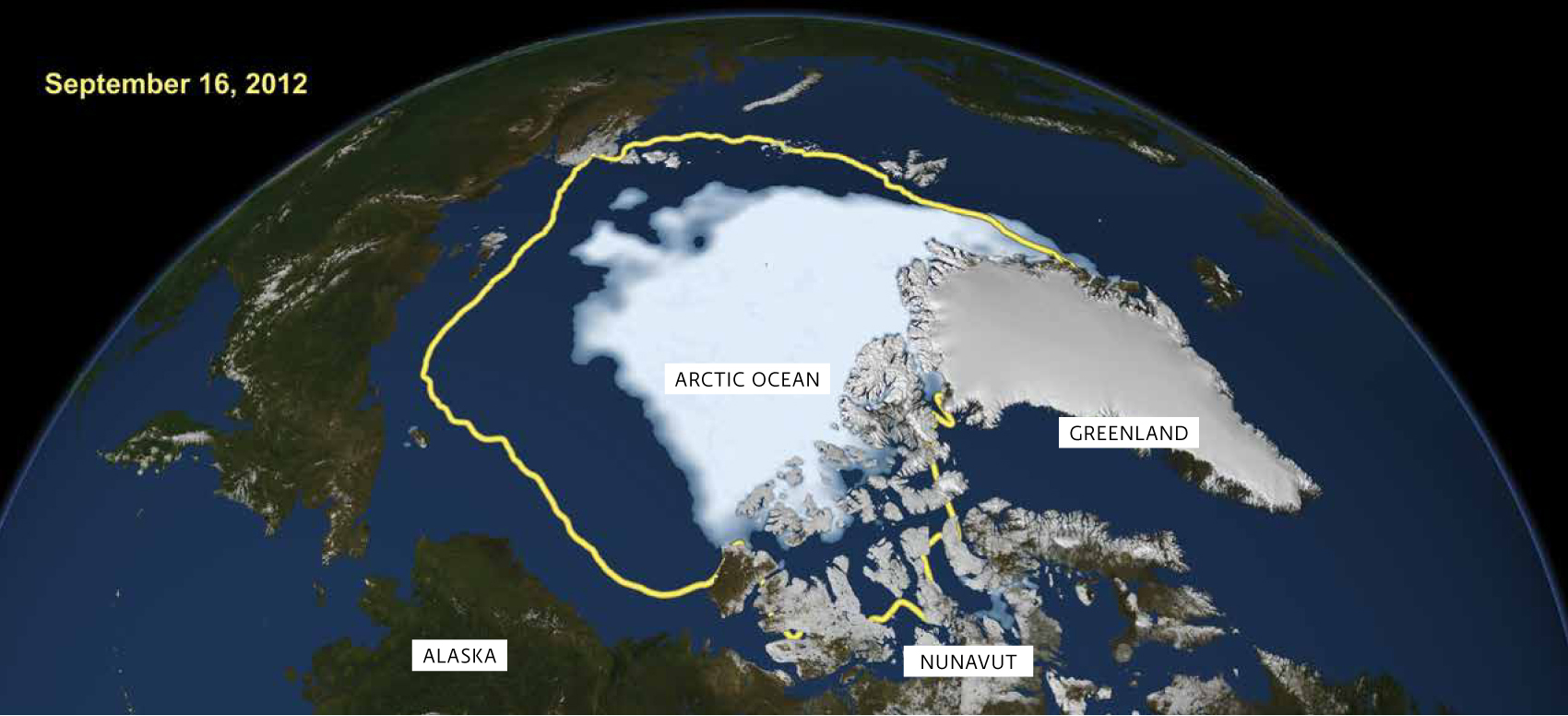

Many climate scientists set the upper limit of CO2 that we should not cross (to avoid substantial negative effects, like the melting of the Greenland Ice Sheet and other events that we cannot reverse) at 560 ppm (double the preindustrial level of 280 ppm). But some scientists place it much lower, at 350 ppm—meaning we must not just reduce the amount of CO2 we release, we must bring down current atmospheric levels. At our current pace (rapid fossil fuel consumption combined with sluggish efforts to curb our emissions) we will probably surpass that 560 threshold before the end of this century. We have already set into motion a chain of events that are dramatically changing the face of the planet, such as glacier and permafrost melt, ocean acidification, and loss of carbon sinks and vital habitats. Exceeding current levels of CO2 will only kick these and other events into an even higher gear as we warm the planet further.

But while the causes of climate change are scientifically well established, the future is still riddled with uncertainty. On the whole, we are likely in for more variable weather—not just warmer weather. While some regions are already enduring heat extremes, other areas will have colder winters as weather patterns shift.

One of the biggest uncertainties is the effect that changes in mean annual temperature and precipitation will have on the world’s forests. Some species may be able to migrate as temperatures rise and their optimum temperature range shifts northward, but which ones? Will spruce and fir species, which thrive in colder environments, disappear from the landscape? Will iconic and economically important trees like sugar maple and jack pine survive in sufficient numbers to sustain Canada’s syrup and timber industries? Will important ecological relationships be fractured as some species move or adapt while others (perhaps prey species or pollinators) do not?

Somewhere, buried in the reams of data that scientists like Frelich have spent decades accumulating, lie clues to answering those very questions.

405