22.9 Mitigation might not be enough.

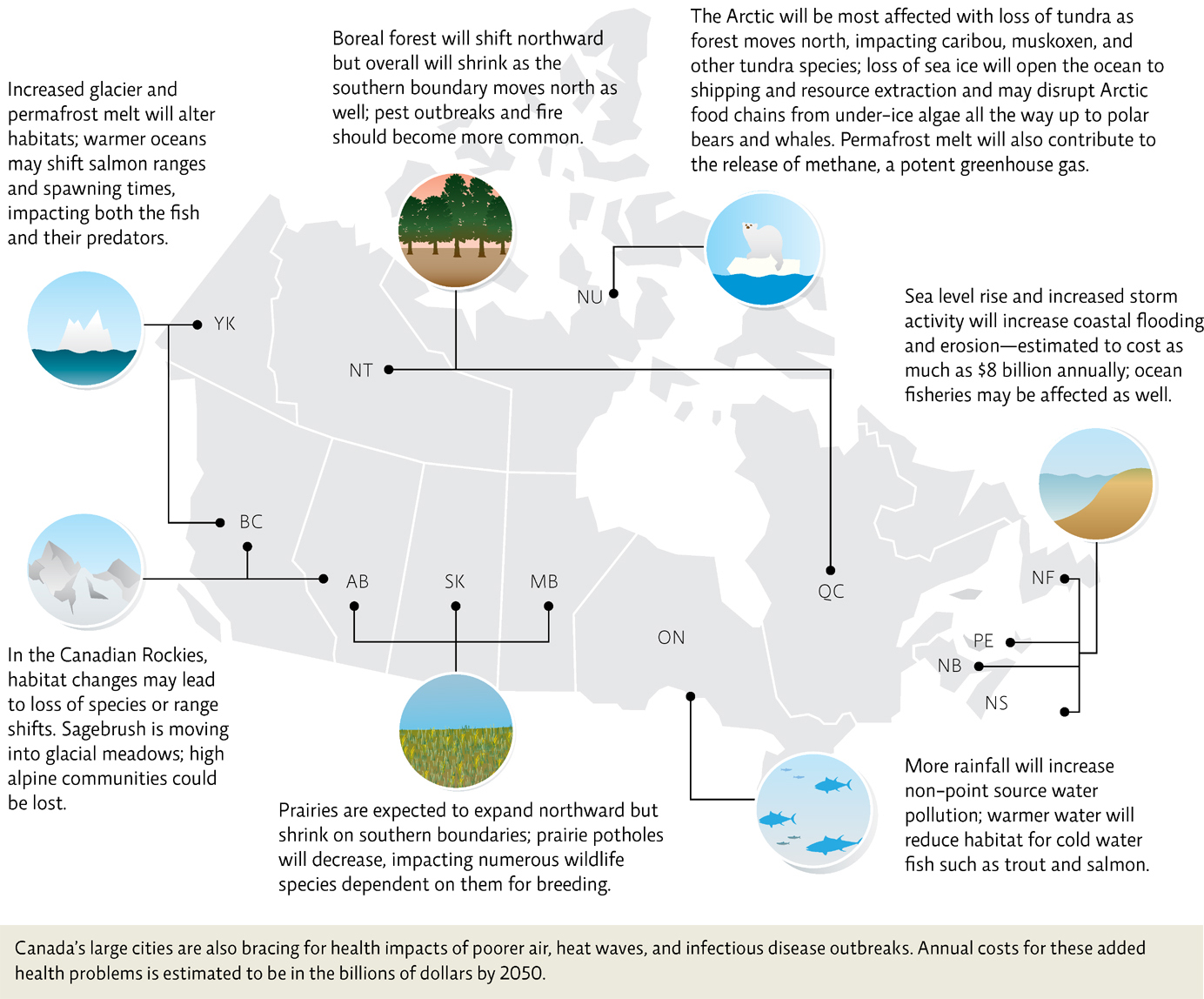

Meanwhile, change is coming to the North Woods. And as birches die off and maples try to expand their territory, as moose falter and pine beetles thrive—those who know the woods best say that mitigation will not be enough. “Resisting climate change at this point is like paddling upstream,” says Frelich. “It might buy us some time, but it’s not going to save the day.” So, he says, we need to start thinking about adaptation: accepting climate change as inevitable and adjusting as best we can. For human societies at large, this means taking steps to ensure a sufficient water supply in areas where freshwater supplies may dry up; it means planting different crops or shoring up coastlines against rising sea levels; it means preparing for heat waves and cold spells and outbreaks of infectious diseases. Canada is now focusing its efforts and funding on adaptation rather than mitigation, taking the positive outlook that new opportunities will arise with climate change. [infographic 22.11]

411

In the North Woods, it might mean facilitation—moving tree species to entirely new ranges where they don’t currently grow, based on the notion that the speed of climate change will make it impossible for natural tree migratory processes, such as seed dispersal, to occur. “The idea is that if we want the forest to adapt, we will have to help it along,” says Frelich.

Facilitation has no shortage of critics, many of whom say such tinkering is both dangerous and unnecessary. “Facilitation is my nightmare,” says John Almindinger, a forest ecologist with Minnesota’s Department of Natural Resources. “That we’ll start to believe we’re smart enough to figure out how to move things. It’s sheer hubris.” Besides, he says, many if not most tree species seem to be moving just fine on their own, along traditional forest migration routes. So far, the U.S. Forest Service agrees; the agency does not allow such bold interventions as planting pines inside the wilderness.

Still, some skeptics are coming around to the idea. “We’ve changed the landscape through development and agriculture,” says Peter Reich, a colleague of Frelich at the University of Minnesota. “And we’ve changed the climate, too, with fossil fuel consumption. So we might now need to change the way we manage wild lands to compensate.”

On this much, everyone seems to agree: if northern Minnesota is to remain fully forested in the coming century, something will have to be done. “We see it already,” says Rajala. “The impact of climate change will be too big to just let nature take its course.”

Select references in this chapter:

Beaubien, E., and Hamann, A. 2011. BioScience, 61: 514–524.

Both, C., et al. 2009. Journal of Animal Ecology, 78: 73–83.

Environmental Protection Agency. 2010. Climate Change Indicators in the United States.

Francis, J. A., and Vavrus, S. J. 2012. Geophysical Research Letters, 39(6): L06801, doi:10.1029/2012GL051000

Frelich, L., and Reich, P. 2009. Natural Areas Journal, 29: 385–393.

Frelich, L., and Reich, P. 2010. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 8: 371–378.

Hitch, A., and Leberg, P. 2007. Conservation Biology, 21: 534–539.

Lenoir, J., et al. 2008. Science, 320: 1768–1771.

NOAA National Climatic Data Center. 2010. State of the Climate: Global Analysis for Annual 2010. http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/sotc/global/2010/13.

Pacala, S., and Socolow, R. 2004. Science, 305: 968–972.

Woodall, C.W., et al. 2009. Forest Ecology and Management, 257: 1434–1444.

BRING IT HOME: PERSONAL CHOICES THAT HELP

The effects of climate change are already being felt by humans, other species, and ecosystems around the globe. By changing our actions, we can decrease the greenhouse gases we produce and show policy-makers that citizens are interested in preventing global climate change.

Individual Steps

Do your part to reduce carbon emissions by conserving energy. Walk or ride a bike instead of driving a car. Share a ride with a coworker rather than driving alone. Negotiate with your employer to telecommute. Live close to where you work or go to school. Reduce your heating and cooling energy use, and always turn off electronics and lights when not in use.

Do your part to reduce carbon emissions by conserving energy. Walk or ride a bike instead of driving a car. Share a ride with a coworker rather than driving alone. Negotiate with your employer to telecommute. Live close to where you work or go to school. Reduce your heating and cooling energy use, and always turn off electronics and lights when not in use.

If your utility company offers renewable energy, buy it.

If your utility company offers renewable energy, buy it.

Reduce the carbon footprint of your food by decreasing the amount of feedlot-produced meat you eat. Buy your food as locally as possible to reduce energy used in transportation.

Reduce the carbon footprint of your food by decreasing the amount of feedlot-produced meat you eat. Buy your food as locally as possible to reduce energy used in transportation.

Avoid air travel, but if you must, buy carbon offset credits if they are available.

Avoid air travel, but if you must, buy carbon offset credits if they are available.

Group Action

Volunteer to help build a zero-energy Habitat for Humanity home.

Volunteer to help build a zero-energy Habitat for Humanity home.

Organize a community lecture on climate change with a local university expert or meteorologist as the speaker.

Organize a community lecture on climate change with a local university expert or meteorologist as the speaker.

Organize an event at your school or community to raise awareness about global climate change and ways to prevent it. Go to 350.org to join a current campaign and for other program ideas.

Organize an event at your school or community to raise awareness about global climate change and ways to prevent it. Go to 350.org to join a current campaign and for other program ideas.

Policy Change

Consider writing, calling, or visiting your member of parliament to tell him or her to support funding for research and development of clean and renewable sources of energy. In addition, insist that your MP support the funding of science, especially those efforts to understand and confront climate change.

Consider writing, calling, or visiting your member of parliament to tell him or her to support funding for research and development of clean and renewable sources of energy. In addition, insist that your MP support the funding of science, especially those efforts to understand and confront climate change.

412