23.1 Can nuclear energy overcome its bad rep?

| CHAPTER 23 | NUCLEAR POWER |

THE FUTURE OF FUKUSHIMA

414

415

CORE MESSAGE

Nuclear energy can create tremendous amounts of power, and with concerns over fossil fuel supplies and climate change, nuclear energy has the potential to be an increasingly important part of the world’s energy future. However, there are serious safety concerns with nuclear power, including vulnerability to natural disasters, radioactive waste disposal, and potential for weapons production.

GUIDING QUESTIONS

After reading this chapter, you should be able to answer the following questions:

What are radioactive isotopes and why are they important for nuclear power?

What are radioactive isotopes and why are they important for nuclear power? How do radioactive isotopes decay and what types of radiation are produced? How dangerous is this radiation?

How do radioactive isotopes decay and what types of radiation are produced? How dangerous is this radiation? How is nuclear energy harnessed to generate electricity in a fission reactor?

How is nuclear energy harnessed to generate electricity in a fission reactor? What problems are associated with the production of nuclear fuel and the disposal of nuclear waste?

What problems are associated with the production of nuclear fuel and the disposal of nuclear waste? What are the advantages and disadvantages of nuclear power?

What are the advantages and disadvantages of nuclear power?

416

417

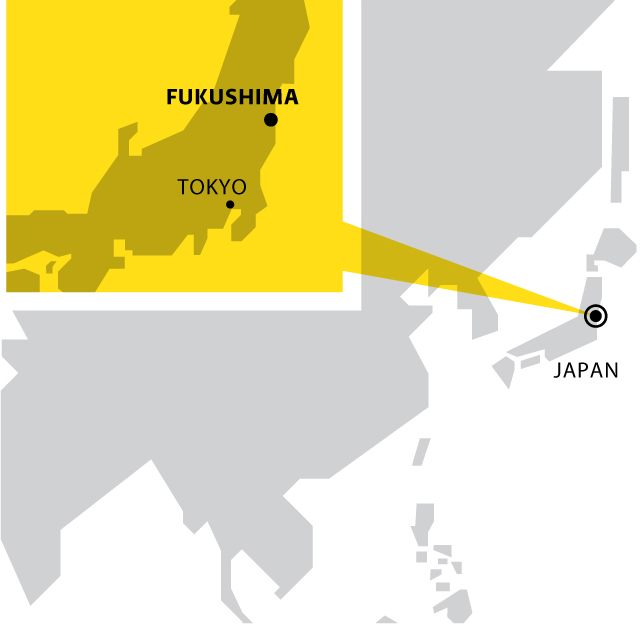

The Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station is a maze of steel and concrete perched right on Japan’s Pacific coast, just 240 kilometres north of Tokyo; its six nuclear reactors supply some 4.7 GW (1 gigawatt = 1 billion watts) of electric power to the country, making it one of the largest nuclear power plants in the world. On March 11, 2011, when a magnitude 9.0 earthquake struck 130 kilometres north of the plant, there were more than 6000 workers inside. The quake caused a power outage, and in the darkness, chaos ensued: men and women groped desperately for ground that would not stabilize beneath their hands and feet, shouting in panic as steel and concrete collided around them. When the shaking stopped, emergency lights came on, revealing a cloud of dust. But that was only the beginning of the disaster.

The earthquake had erupted beneath the ocean floor, triggering a tsunami that would arrive at the plant in two distinct waves. The first wave was not big enough to breach the 10-metre-high concrete wall that had been built between the plant and the sea. But the second wave, a fearsome mass of water that came 8 minutes later, was. At four storeys tall, it bulldozed a string of protective barriers, sent buses and cars and trucks careening into pipes and levers and control panels, and eventually settled, in deep black pools, around the reactors themselves.

They were the strongest earthquake and largest tsunami in the country’s long memory. Together, they would claim some 20 000 lives along a 400-kilometre stretch of coast (roughly equal to the driving distance between Toronto and Ottawa). But as the ground steadied and the water subsided, the world’s attention would quickly turn to a third disaster, even more precarious and potentially deadly than the first two: the risk of nuclear meltdown at Daiichi.

WHERE IS FUKUSHIMA, JAPAN?

It’s no surprise that the story of nuclear power pivots on calamity. Ever since its potential was first demonstrated, humankind has scurried relentlessly between two competing goals—the desire to harness nuclear energy for our own ends, and the impulse to protect ourselves from its destructive capacity. When the ground trembled beneath Fukushima, concerns over greenhouse gases and global warming had been pushing much of the world—including Canada and the United States—toward the former. As the people of Japan scrambled to respond, the world watched closely.