25.3 Biofuels can come from unexpected sources.

Back in Minnesota, Tilman set about testing to see why half his grasslands seemed resistant to drought. After trying “a whole variety of things,” Tilman and his team came to a simple conclusion: the plants growing in the most diverse areas—those with up to 20 species of grasses and flowers—were the most able to weather periods of drought. Tilman was baffled. Why should plants competing with each other be more successful during a drought?

He and his team of ecologists decided to study the question empirically. They spread out under a bright blue sky at the Cedar Creek Reserve in Minnesota and planted a smorgasbord of seeds among 152 plots, each plot roughly the size of half a tennis court. The plants began to sprout: gold bunches of junegrass, stately spires of dark blue lupine, bright yellow tufts of goldenrod, and tall, spiky western wheatgrass. Some plots had only 1 species, some 2, others up to 16. Each plant was a perennial, meaning it would grow back every year, differing from annual plants such as corn and soybeans, which must be replanted each year. The team used no fertilizer and only watered plots in the first few weeks after planting.

One of the species was switchgrass, a common North American perennial that grows thick and tall (up to 3.5 metres), with roots penetrating 3 metres into the soil. As Tilman watched his plants grow, he was not the only person thinking about switchgrass. The crop was rapidly becoming a household name for another reason—as a potential source of biofuels.

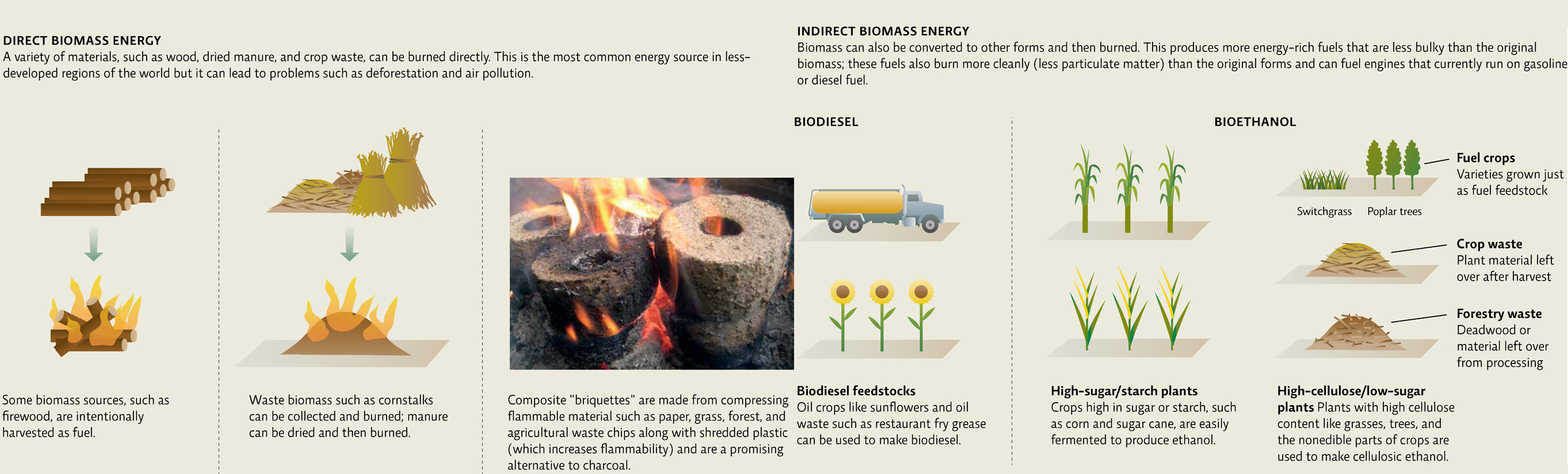

Often, biofuels are derived from fuel crops, those specifically grown to make biofuels. For instance, bioethanol can be derived from crops such as corn and sugarcane during a process of fermentation and distillation, similar to that used to make alcoholic beverages. Biodiesel, a different kind of biofuel produced from oils, is most often made from high-oil crops like soybeans. [infographic 25.1]

457

Today, ethanol is primarily used as an additive, mixed with gasoline to produce a cleaner burning fuel. It’s also more corrosive than gasoline, so mixtures at the gas pump typically contain no more than 10% ethanol (E10 fuels). Some so-called “flex fuel” vehicles are equipped to use up to 85% ethanol mixtures, and thousands of these vehicles are on the road today. Because ethanol has only about two-thirds of the energy found in gasoline, however, it is not suitable for high-demand engines like those in airplanes and large trucks. Biodiesel, however, is more energy-rich than ethanol, and can be used in these applications; it can also be used directly in diesel engines, with little or no modification.

There’s another convenient source of biofuels—biowaste, often in the form of organic leftovers such as crop residues, garbage, or manure. For instance, even though ethanol usually comes from corn and sugarcane, it can also be produced from the stalks, husks, and leaves of plants left over after a crop has been harvested. Any kind of organic material has the potential to be converted to liquid biofuels such as ethanol, or to a gaseous product similar to natural gas known simply as biogas.

The idea of converting waste to energy is appealing—it has the dual benefit of both producing energy and dealing with waste at the same time. For instance, communities are struggling to deal with methane released from decomposing landfill waste, which acts as a potent greenhouse gas, each molecule trapping 25 times more heat in the atmosphere than one of carbon dioxide. Some communities are now working to capture that gas for energy use. Of 2300 municipal solid waste landfills in the United States, more than 450 have landfill gas projects. Canada has 64 landfill gas recovery facilities.

458

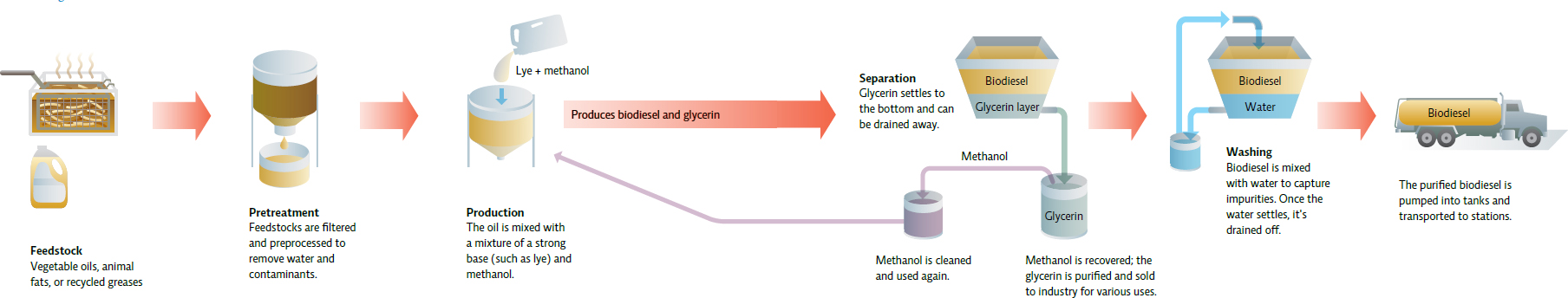

Biodiesel can also easily be made from waste such as animal fats or waste oil. Indeed, a new industry is emerging around the disposal of used fryer oil from restaurants; once a liability that restaurants paid to have hauled away, this oil can be picked up free of charge by biodiesel entrepreneurs who turn it into a fuel that can be sold to local diesel users.

At the moment, biodiesel comprises only a small portion of the biofuels produced, and cannot be used in gasoline engines. But biodiesel buses and recycling trucks are on the road all around North America. Currently, biodiesel is the only biofuel to be certified by the EPA, having passed the safety tests required by the Clean Air Act.

Biodiesel can also be produced on a small scale. Across North America, communities are taking matters into their own hands and forming small biodiesel cooperatives that produce relatively small amounts of biofuel for personal use. In Vancouver, British Columbia, the Vancouver Biodiesel Co-op provides its 300 plus members with high-quality, certified biodiesel from local-source supplier Lower Mainland Biodiesel. The Co-op tracks its contribution to CO2 emission reduction in real time, which is already over 180 967 kilograms. [infographic 25.2]

People have spent the last 100 years trying to use biomass to power engines: Henry Ford’s first Model T, rolled out in 1908, was designed to use ethanol as fuel. But it wasn’t until the second half of the 20th century that biofuels became big business—and more recently, a hotbed of controversy.

459