25.4 Turning grass into gas is less environmentally friendly than it sounds.

Despite the attraction of putting waste to work, today most biofuels are made from crops grown specifically for energy use. Biodiesel, for instance, typically stems from crops with a high oil content, such as soybeans or canola (rapeseed), and these are the top two biodiesel crops in Canada. For decades, sugar cane has served as the primary source of ethanol in Brazil. But in North America, corn is the ethanol fuel crop of choice.

In the mid-1970s, fuel shortages revived public interest in alternatives to fill cars, fuel stoves, and light homes. As the world’s leading producer of corn, the United States had the infrastructure in place to create corn-based ethanol production facilities, which began to pop up in rural farming towns all over the midwestern United States. Between 1999 and 2009, the total number of operating ethanol plants in the United States tripled, growing from 50 to more than 150. The Energy Policy Act, passed by the U.S. Congress in 2005, required that the country boost its biofuel production to 7.5 billion gallons (28 billion litres) by 2012. Only 4 years later, in 2009, the country had exceeded that goal, topping 11 billion gallons (40 billion litres). Today, nearly 50% of America’s gasoline contains some amount of ethanol, according to the American Petroleum Institute. In Canada, as of 2011, all gasoline has been required to have at least 5% renewable content, and as of 2013, all diesel must have at least 2% renewable content.

In the beginning, biofuels were welcomed as an ideal green solution, reducing our dependence on foreign oil and saving the planet along the way. But slowly, that sparkling image began to fade.

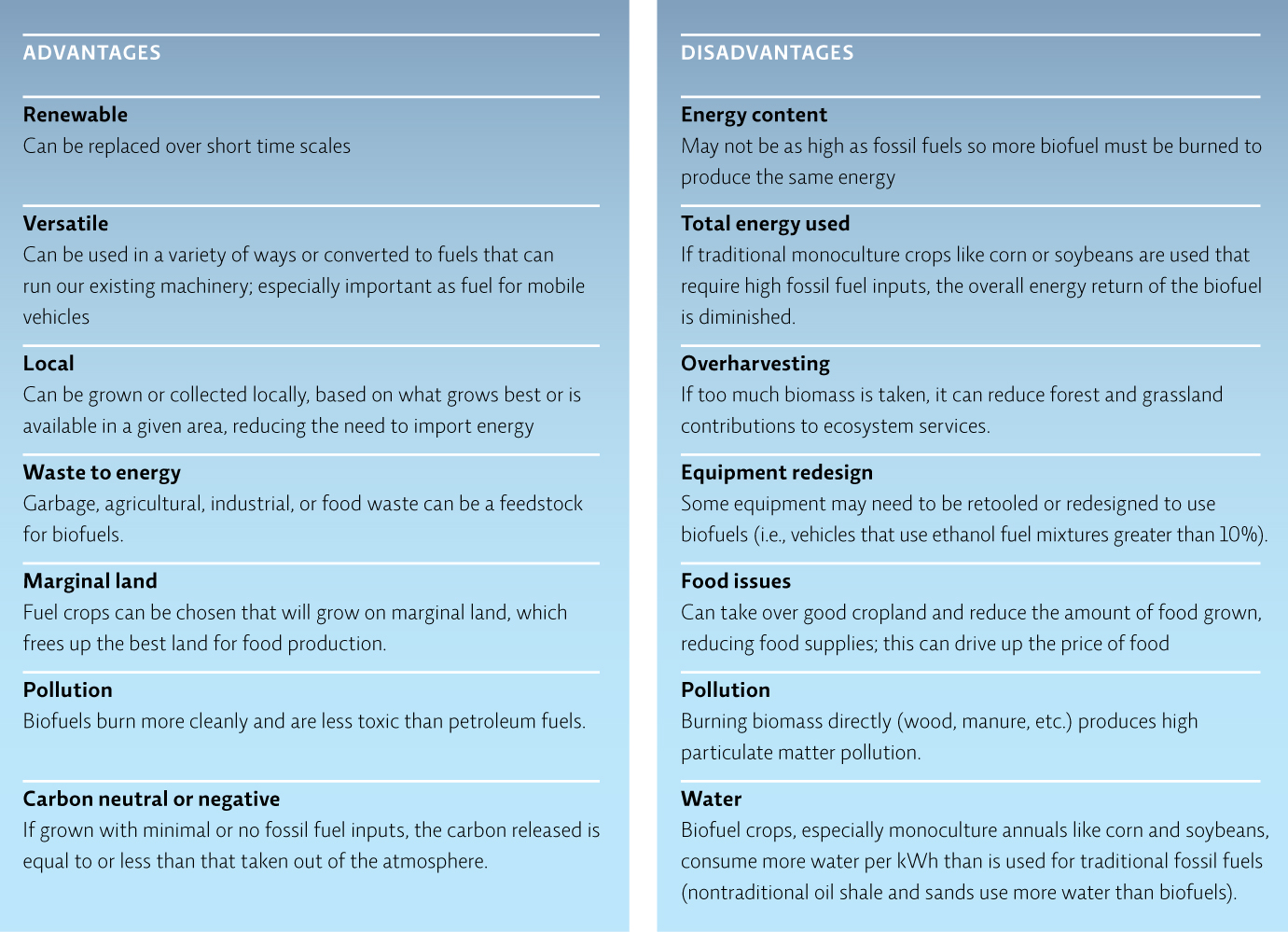

Over time, experts realized that the initial attempts to create biofuels weren’t much more environmentally friendly than the fossil fuels they were intended to replace. Corn is one of the most energy-intensive crops to grow and harvest, requiring energy inputs like fertilizers and pesticides (made from fossil fuel), as well as fuel needed for the operation of farm machinery; these early corn ethanol projects used as much (or almost as much) energy as they produced. Water was also a concern: one study estimated that a car running on ethanol uses the equivalent of 120 litres of water for every kilometre (compared to 2 to 3 litres of water used to produce a litre of gasoline).

Another worry is that many natural ecosystems are being converted to farmland for biofuels, endangering native species that live there, such as orangutans in the rainforests of Malaysia and African elephants in Ethiopia. These biofuel crops also displace food crops—farmers who might normally grow corn for food or animal feed are growing it for fuel. This switch drove up the price of corn in 2007, and caused riots in Mexico, Haiti, and other nations around the world where corn is a staple food item. And clearing land for biofuel crops releases carbon stored in soil and plants, adding greenhouse gases to the atmosphere as well as disrupting all the benefits those ecosystems provide, such as habitat for a variety of organisms. In addition, the use of crop waste to produce biofuels has its drawbacks—namely the removal of material that normally would have been plowed back into the soil to decompose and add back nutrients. [infographic 25.3]

460

Advances in recent years, mostly in increased production per hectare, now make corn a better option than it used to be. Even though early attempts to make ethanol from corn often used more energy than they produced, the U.S. Department of Energy recently estimated corn’s EROEI (energy return on energy investment) at 1.38, meaning it produced 0.38 units of energy for every unit of energy invested. (By comparison, the EROEI of coal is >80.) But even if the energy return could be further improved, should we be using prime farmland to produce a fuel crop? Is there a way to grow biofuel feedstocks on marginal lands? Along with many other researchers, Tilman was discovering some interesting insights on just how to do that.