26.1 In the Bronx, building a better backyard

| CHAPTER 26 | URBANIZATION AND SUSTAINABLE COMMUNITIES |

THE GHETTO GOES GREEN

472

473

CORE MESSAGE

Cities can be both an environmental blessing and a curse. Using green strategies to plan or retrofit cities can benefit citizens, business, and the environment—not to mention reduce environmentally related health problems and degradation of natural resources.

GUIDING QUESTIONS

After reading this chapter, you should be able to answer the following questions:

What is the pattern of global urbanization and megacity growth in recent decades?

What is the pattern of global urbanization and megacity growth in recent decades? What are the trade-offs associated with cities or urban areas?

What are the trade-offs associated with cities or urban areas? What is environmental justice? How does urban flight contribute to and result from environmental justice problems?

What is environmental justice? How does urban flight contribute to and result from environmental justice problems? What environmental problems does suburban sprawl generate?

What environmental problems does suburban sprawl generate? How can we create cities that are environmentally sustainable and promote a good quality of life for the residents?

How can we create cities that are environmentally sustainable and promote a good quality of life for the residents?

474

As she walked her dog Xena—a scruffy puppy she had found tied to a tree in her South Bronx neighbourhood—Majora Carter considered her options. The 32-year-old aspiring filmmaker had moved back home to save money while she attended graduate school. Initially, she had wanted as little to do with the decaying neighbourhood as possible. But then she’d gotten involved in a local artists’ group and taken work at a community development centre. Now, a colleague at the city parks department was offering her a $10,000 grant to come up with a waterfront development project for her neighbourhood. Carter was balking.

At the moment, she and her neighbours were busy fighting a mammoth waste facility that the city was trying to move from Staten Island to the East River waterfront. With 30 transfer stations in the South Bronx, their tiny parcel of New York already handled 40% of the entire city’s commercial waste, not to mention having four power plants, two sludge processing plants, and the largest food distribution centre in the world. All told, some 60 000 diesel trucks passed through the neighbourhood every week. In exchange for this burden, area residents boasted the highest asthma and obesity rates in the country, along with some of the poorest air quality. Another waste facility would only make matters worse. Consumed with this battle, Carter wasn’t sure she had the time or energy to take on a development project.

Besides, the idea of developing waterfront property in the South Bronx seemed a bit naive to her. Like most of her neighbours, Carter had lived in the neighbourhood most of her life; she knew full well how inaccessible the surrounding river was to residents.

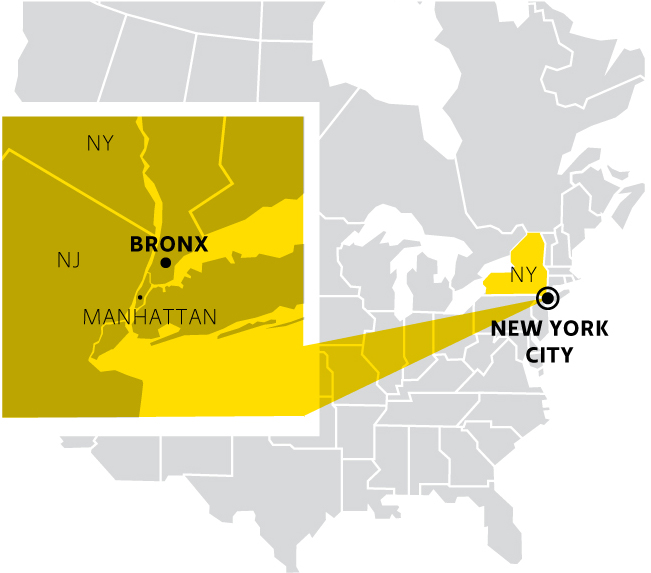

WHERE IS THE BRONX, NEW YORK?

The waterfront—all of it—had long been claimed by industry. There was simply nothing left to develop, she thought, as she and Xena made their way along their usual route—past the transfer station, roaring with diesel-powered, garbage-filled 18-wheelers, along a winding string of garages filled with auto glass shops, metal work, and produce shipments.

And then Xena began pulling her toward an abandoned lot, one they had passed a million times without bothering to notice. After a futile effort to resist, Carter allowed herself to be led down a garbage-strewn path, through a ramble of towering weeds. There at the end, sparkling in the early morning light, was the East River. Carter stood in awe. How many other forgotten patches of waterfront were there, she wondered? Maybe the river wasn’t so inaccessible after all.