26.2 More people live in cities than ever before.

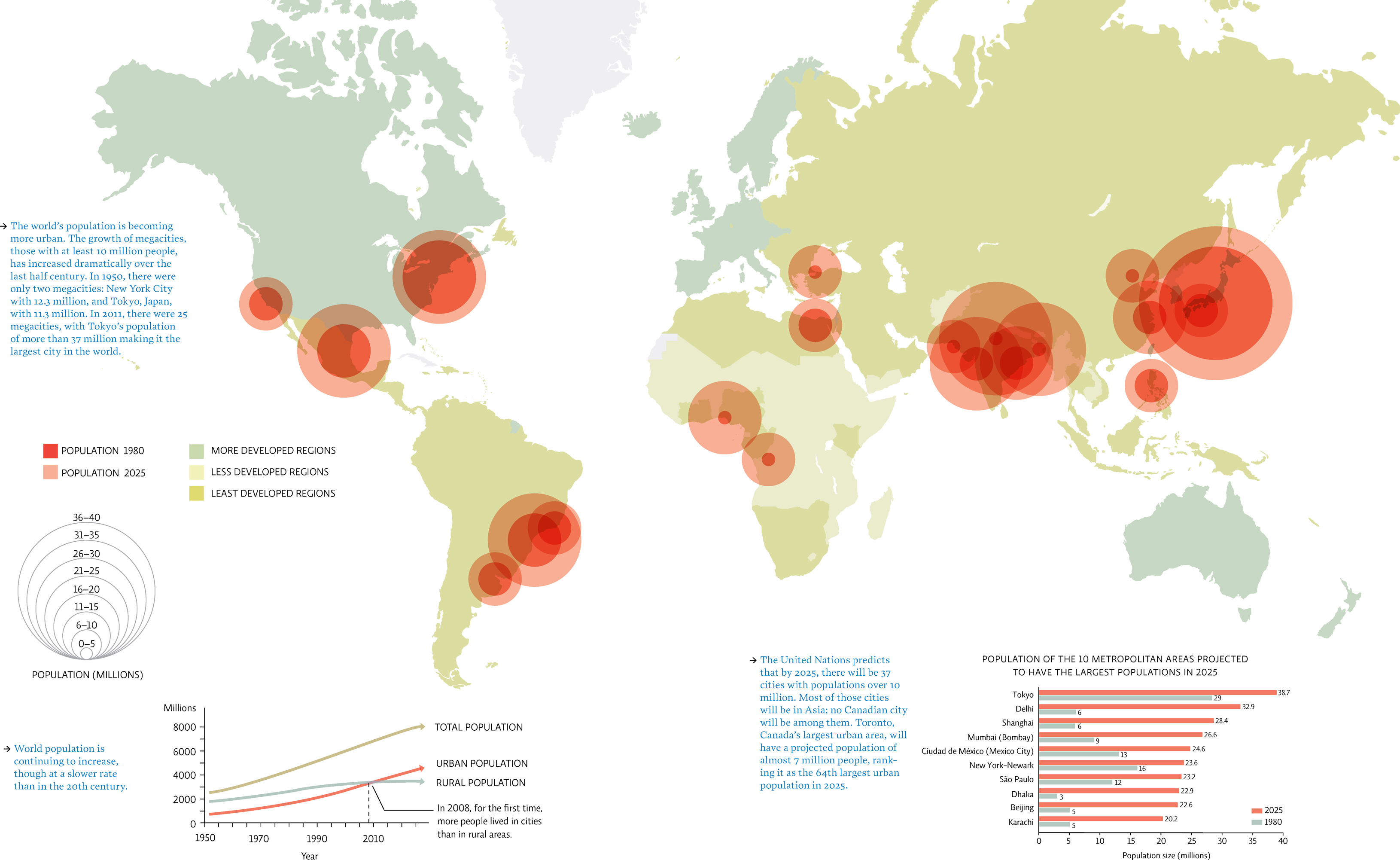

For the first time in human history, more than half the world’s population lives in urban areas—densely populated regions that include both cities and the suburbs that invariably surround them. In Canada the proportion is even higher: 80% of Canadians are urban dwellers. Urbanization, the migration of people to large cities, is happening around the world at an unprecedented rate. As global population swells, rural lands are morphing into urban and suburban ones, and ordinary cities are growing into megacities—those with at least 10 million residents. North America has only 3 megacities—Mexico City and New York City (approximately 20 million each) and Los Angeles (approximately 13 million). Canada’s largest city, Toronto, has fewer than 6 million inhabitants. [infographic 26.1]

475

476

477

478

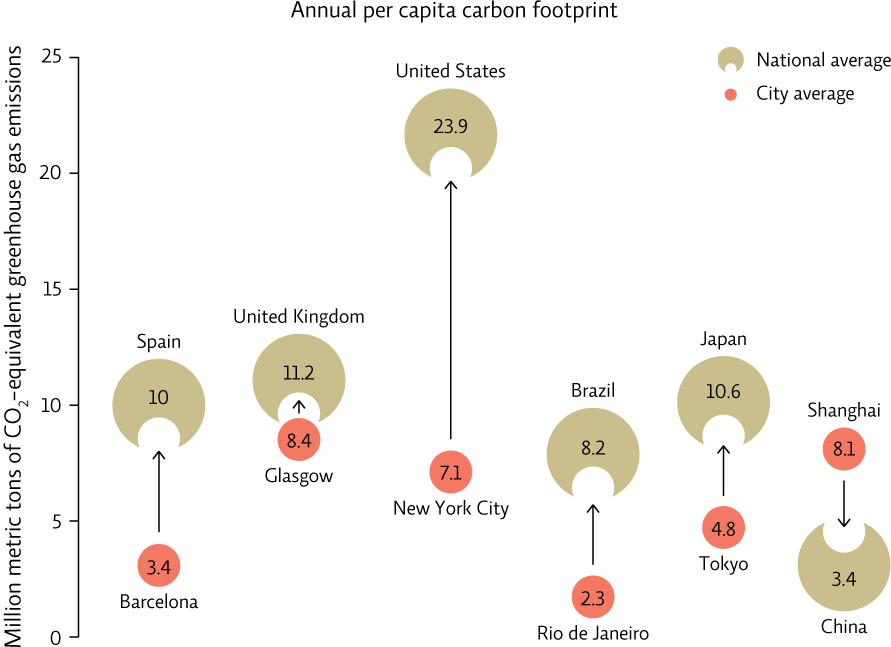

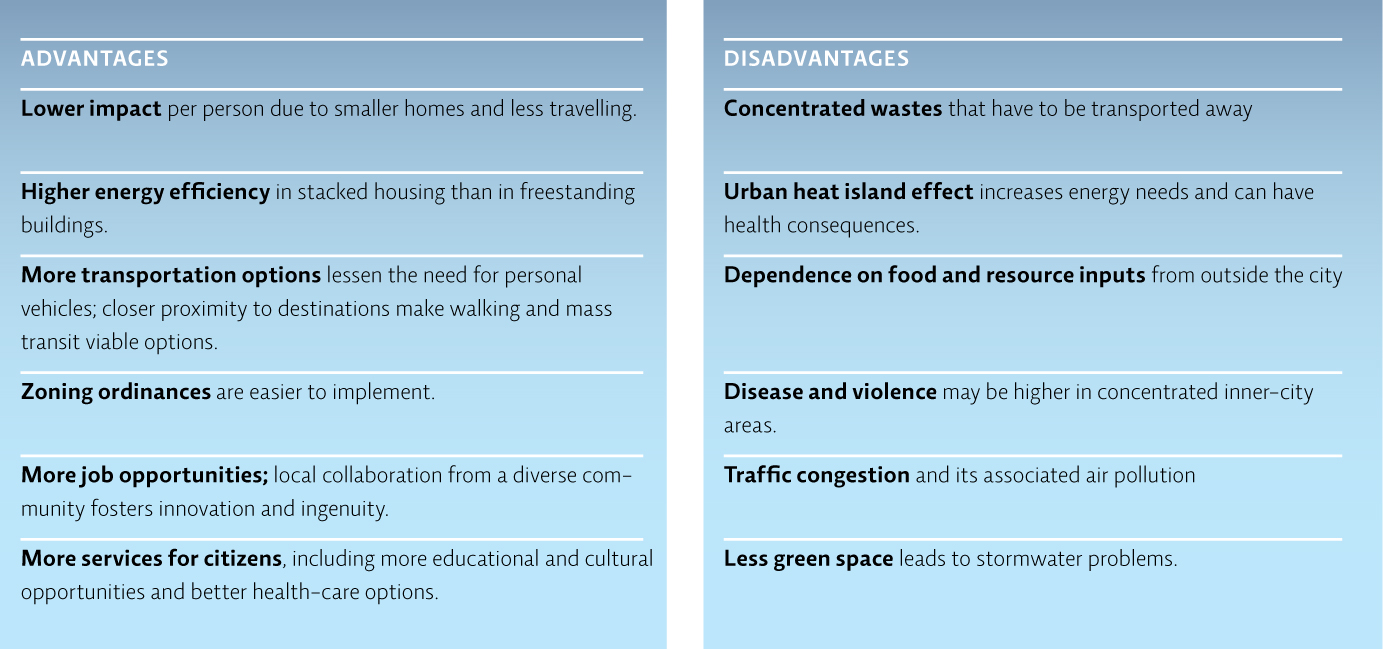

To be sure, cities bring some obvious advantages to their inhabitants: more job opportunities, better access to education and health care, and more cultural amenities, to name a few. But as far as the environment is concerned, urbanization is both a blessing and a curse. On the plus side, concentrating people in smaller areas (building up rather than out) can reduce development of outlying agricultural land and wild spaces and thus protect existing farms and ecosystems. Higher population densities also make some environmentally friendly practices more cost effective. For example, it’s easier to implement recycling and mass transit programs in cities because there are more people to share the cost of these services. Living in smaller homes that are closer to needed amenities and having access to mass transit also decreases the energy use—and carbon footprint—of urban dwellers, compared to those who live in suburban areas. [infographic 26.2]

On the minus side, large cities are locally unsustainable: they require the import of resources like food and energy and the export of waste. Because they are densely populated, most cities are also hotbeds of traffic congestion (which pollutes the air) and sewage overflow (which pollutes the water).

Another problem stems from the way cities are designed and built—namely, the replacement of vegetation with pavement. Plants absorb water, filter air, and regulate area temperatures; pavement and concrete do not. In fact, the blacktop that covers most cities prevents rainwater from being absorbed into the ground, which in turn diminishes groundwater supplies and can lead to flooding (see Chapter 16). Cities also require an abundance of energy. This trifecta—too few plants, too much pavement, and high energy use—conspires to trap the solar heat that is absorbed and reflected by buildings, making most cities warmer than their surrounding countrysides. This phenomenon is known as the urban heat island effect. [infographic 26.3]

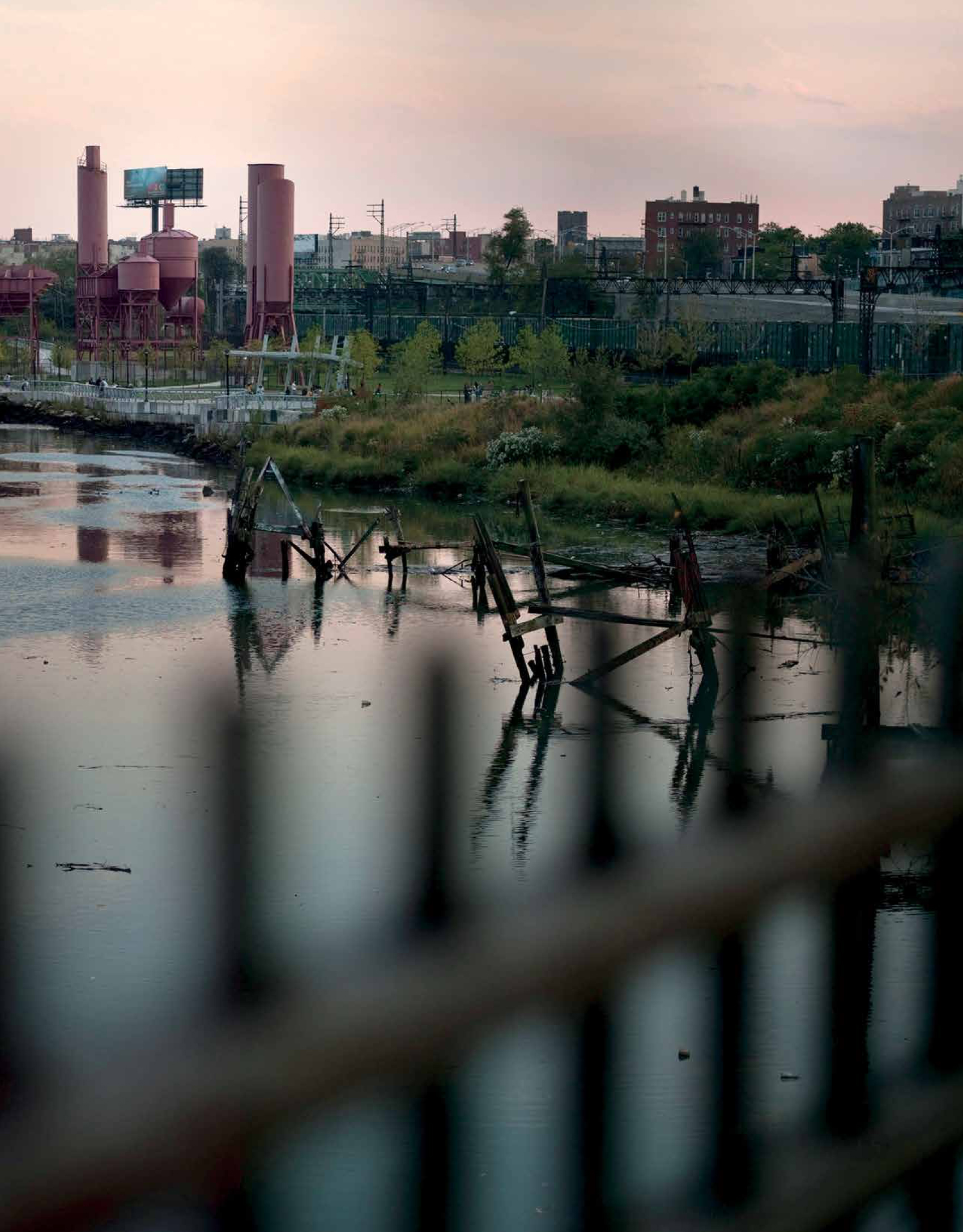

All urban dwellers are vulnerable to the health effects associated with pollutants. But in most cities, the pros and cons of city living are unevenly realized. For example, Toronto is a wealthy, populous city, but most of the cultural amenities, top-notch health-care facilities, and job opportunities are concentrated in the central downtown area, while poorer communities such as South Riverdale were historically chosen as the sites of industrial facilities that pollute the area. This imbalance has spawned a whole new area of activism known as environmental justice, based on the idea that no community should be saddled with more environmental burdens and less environmental benefits than any other.

The movement is particularly relevant in the most impoverished cities in the world. Mumbai, the largest city in India, has nearly 20 million people. Almost 7 million of these are slum dwellers who live in horrid, overcrowded conditions—as many as 45 000 people per hectare—without adequate sanitation or running water. One report showed only one toilet per 1440 residents. Globally, more than 1 billion of the world’s people live in slums, mostly in large cities in developing countries.

479

480

With 90% of future population growth predicted to occur in large cities, urban planners are desperately searching for ways to create cities where the basic needs of residents are met and where environmental benefits outweigh environmental costs. The story of how the South Bronx waterfront was lost and then reclaimed provides important lessons about how to do this.