26.5 The future depends on making large cities sustainable.

Sustainable cities are those where the environmental pros outweigh the cons—where sprawl is minimized, walkability is maximized, and the needs of inhabitants are met locally. In recent years, urban planners have come up with a wide range of strategies for accomplishing these goals. To achieve self-sufficiency, for example, a sustainable city might maintain a mixture of open and agricultural land along its outskirts. Such land could provide a large part of the local food, fibre, and fuel crops, along with recreational opportunities and ecological services. Waste and recycling facilities could also be located nearby, along with other enterprises aimed at producing resources needed by area residents. To stave off sprawl, the same city might establish urban growth boundaries—outer city limits beyond which major development would be prohibited. Keeping any outward growth that does occur as close to mass transit as possible minimizes the impacts of transportation, just as building “up” (a parking garage) rather than “out” (an expansive parking lot), minimizes the amount of land used. To encourage more walking and less driving, zoning laws might allow for mixed land uses, where residential areas are located reasonably close to commercial and light industrial ones.

Of course, building an ideal city from scratch is easy compared with the task of overhauling an existing city, especially when that city is as densely populated and ever-expanding as New York or Toronto. Upgrading decaying infrastructure like roads, public places, and sewage and water lines can be more expensive than new construction and the process is disruptive to residents. Urban retrofits are certainly possible but sometimes their very success raises property values to the point that the original residents can no longer afford to live in their own neighbourhoods. Even so, there are plenty of ways that cities can push themselves into the environmental plus column. For example, infill development—the development of empty lots within a city—can significantly reduce suburban sprawl. And even the most car-friendly of cities has a range of options for reducing traffic congestion and the air pollution that comes with it: reliable public transportation, car sharing programs that allow residents to use cars when needed for a monthly fee, and sidewalks and overhead passageways that allow pedestrians to safely cross busy roads. The cumulative effect of strategies like these, which help create walkable communities with lower ecological footprints, is known as smart growth. [infographic 26.6]

Persuading people to support smart growth, as Carter and her colleagues soon discovered, was a matter of showing them that the benefits could be economic as well as environmental. “You need to show them what we call the triple bottom line,” says James Chase, vice-president of SSBx (and Carter’s husband), referring to the economic, social, and environmental impacts of any decision (see Chapters 1 and 5). “Developers, government, and residents all need some tangible, positive return.” A major park project would surely be a boon for all three. Developers would be guaranteed millions in waterfront development contracts. Residents could look forward to cleaner air and water, a prettier neighbourhood, and better health as a result. The government would save a bundle in health-care costs. The greenbelt would also spur the local economy—such a vast stretch of public space would attract street vendors, food stands, bicycle shops, and sporting goods stores.

It would also require a green workforce. Some of the undeveloped property that Carter and her neighbours hoped to convert into parkland was contaminated with hazardous waste. These sites are called brownfields, and they require a special type of cleanup, or remediation, before they can be developed.

The surrounding wetlands, suffering from decades of neglect, would also need to be restored. And maintaining the new trees, plants, and parks they hoped to create would require a workforce trained in urban forestry. Anxious to claim these emerging professions—all of which promised job security and living wages—for their own community, Carter and her neighbours launched Bronx Environmental Stewardship Training—a green job training program that teaches South Bronx residents the principles of urban forestry, brownfield remediation, and wetland restoration. Program participants—many of them ex-convicts and high school dropouts facing prison time—also learn how to install solar panels and retrofit older buildings to make them energy efficient. So far, 82% of the participants have found jobs in the green economy and 15% have gone on to college.

485

486

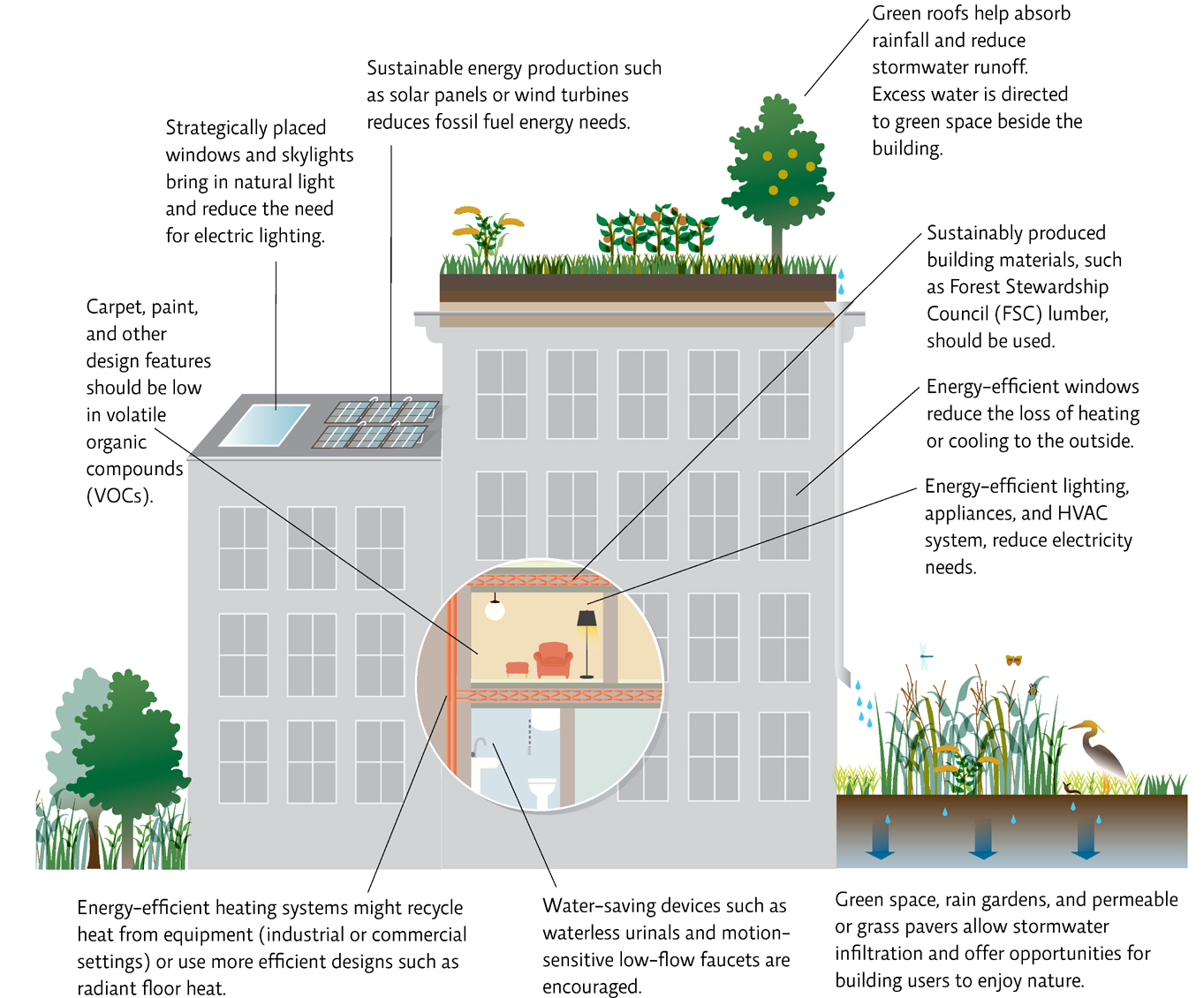

The green economy includes a movement known as green building, that is, the construction of buildings that are better for the environment and the health of those who use them. The best green buildings are awarded a LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) certification, which is internationally recognized. The Bronx Library Center is a silver-certified LEED building. It earned the silver certification by recycling 90% of the waste materials created during the construction of the building, using architectural design and efficient heating and cooling systems to save 20% of energy costs, and using sustainably grown wood in 80% of the construction lumber.

487

Carter and her team also launched Smart Roofs, a green-roof and green-wall installation company. Green roofs are one type of rain garden—an area seeded with plants suited to local temperature and rainfall conditions (see Chapter 16 for more on rain gardens). A 2004 study by the New York City Department of Design and Construction found that consumers could save more than $5 million in annual cooling costs if green roofs were installed on just 5% of the city’s buildings. According to a study by Columbia University, the same amount of green roofing could achieve an annual reduction of 318 000 metric tons of greenhouse gases. And Riverkeep, an environmental nonprofit, found that green roofs can retain over 3 cubic metres of stormwater for every $1,000 of investment— easing pressure on the city’s overburdened sewer systems and mitigating water pollution from storm runoff. Green roofs also lessen the urban heat island effect. [infographic 26.7]

Green roofs require factory-made artificial soil (ordinary topsoil is too heavy and can clog drainage systems). And to prevent leaks, a specially designed membrane system must be installed. Producing the artificial soil, creating and installing the membranes, and planting the right mix of species to trap water requires labour—skilled labour. “Once we figured out the employment factor, we had a win-win-win,” says Chase. “There’s all these jobs—good jobs—that are going to take off in the next decade, but that not a lot of people know how to do right now. It was a clear opportunity for us.” To help the company take off, SSBx secured tax credits from the state legislature. Building owners who install green roofs on at least 50% of their available rooftop now receive a 1-year property tax credit of up to $100,000. Carter offered up her own roof as the first test case.

By the time the Hunts Point Riverside Park opened, dozens of cities across North America—from Vancouver to Miami—had taken up the mantle of sustainability and smart growth.

Select references in this chapter:

Beckett, K., and Godoy, A. 2010. Urban Studies, 47: 277–301.

Dodman, D. 2009. Environment and Urbanization, 21: 185–201.

Ewing, R., et al. 2003. American Journal of Health Promotion, 18: 47–57.

United Nations Population Division. 2008. An Overview Of Urbanization, Internal Migration, Population Distribution And Development In The World. New York: United Nations.

BRING IT HOME: PERSONAL CHOICES THAT HELP

A sustainable community is one that promotes economic and environmental health and social equity. It is one in which the health and well-being of all citizens are considered, while those citizens help implement and maintain the community.

Individual Steps

Research products before you purchase them to understand the impact of your consumption choices (www.goodguide.com). Investigate and support sustainable businesses in your area (www.greendirection.ca).

Research products before you purchase them to understand the impact of your consumption choices (www.goodguide.com). Investigate and support sustainable businesses in your area (www.greendirection.ca).

If you have a balcony or yard, plant flowers, vegetables, or trees.

If you have a balcony or yard, plant flowers, vegetables, or trees.

Support local businesses by shopping and dining close to home.

Support local businesses by shopping and dining close to home.

Group Action

Join neighbourhood cleanup days. If you can’t find one, organize one.

Join neighbourhood cleanup days. If you can’t find one, organize one.

Start a petition to get more bike lanes in your city. Ride public transit more often.

Start a petition to get more bike lanes in your city. Ride public transit more often.

Find out how colleges and universities are working toward sustainable practices at www.AASHE.org.

Find out how colleges and universities are working toward sustainable practices at www.AASHE.org.

Policy Change

Attend a meeting of your city or regional council and ask members to look into smart growth opportunities.

Attend a meeting of your city or regional council and ask members to look into smart growth opportunities.

See how well you can plan for a sustainable community. Play the new PC strategy game Fate of the World and see how policies you put in place impact global climate change, rainforest preservation, and resource use.

See how well you can plan for a sustainable community. Play the new PC strategy game Fate of the World and see how policies you put in place impact global climate change, rainforest preservation, and resource use.

488