3.4 Information sources vary in quality and intent.

The ability to distinguish between reliable and unreliable sources is referred to as information literacy. It’s the key to drawing reasonable, evidence-based conclusions about any given issue or topic. It is especially useful when trying to understand the arguments for and against potentially harmful substances that are also commercially important, such as BPA. In such instances, hyperbole and misinformation abound.

Much of what we learn in science class today will be outdated 5 years from now—not because we are wholly ignorant in the present, but because we will know so much more in the future.

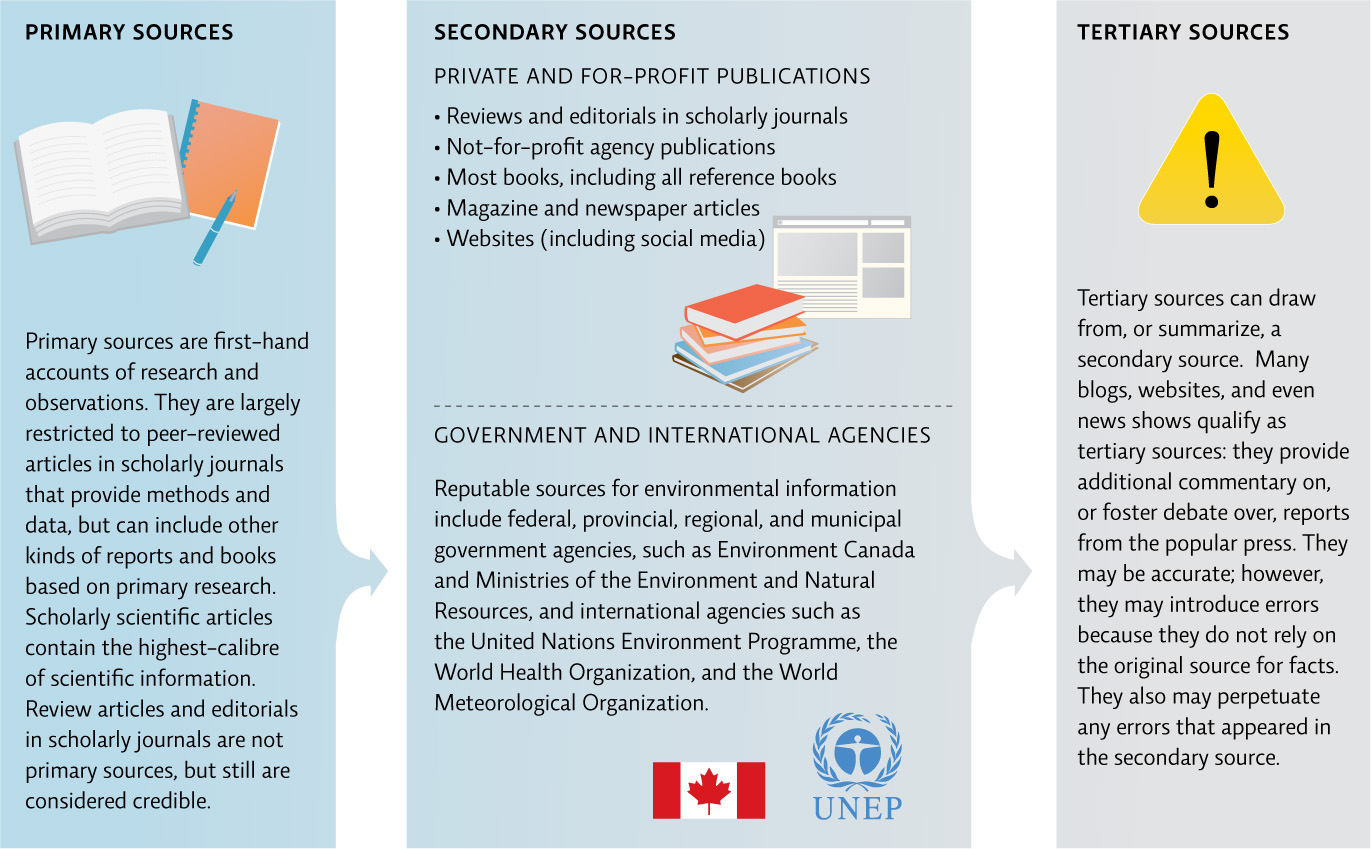

Primary sources are those that present new and original data or information, including novel scientific experiments published in scientific journals. Almost all of these reports, or papers, are rigorously evaluated through peer review—a process whereby experts in the field (a panel of the author’s “peers”) assess the quality of the study’s design, data, and statistical analysis, as well as the soundness of the paper’s conclusions. Good studies are published; bad ones are rejected.

Secondary sources present and interpret the information from primary sources, such as scientific review articles and many reports from the popular (non-scientific) press.Tertiary sources are those that present and interpret information from secondary sources. [infographic 3.1]

Because the popular press runs on catchy sound bites and easily digestible bits of information, news outlets (both secondary and tertiary) tend to oversimplify the results of individual studies, or present them as if they provided definitive answers. But there are rarely easy answers to environmental questions, and science is almost never as straightforward as we would like it to be. In fact, by its very nature, science is incremental; each study is just one small piece of a much larger puzzle, and existing hypotheses are subject to endless revision and qualification as new bits of data trickle in.

43