3.7 Critical thinking skills give us the tools to uncover logical fallacies in arguments or claims.

In 2010, Lanphear and a group of experts gathered in Ottawa, at a meeting convened by the World Health Organization and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, to discuss the potential effects of BPA. By then, there had been hundreds of studies about BPA, according to Lanphear, but half of the toxicologists at the meeting said many of the studies were flawed—BPA was administered incorrectly to the animals used in the study, or the doses were wrong, or perhaps the scientists looked at the wrong health outcomes to determine its effects. As a result, the report from the meeting simply highlighted the “considerable uncertainty” in our knowledge, and recommended further study.

50

It’s important for everybody—not just scientists—to think carefully about the data they are presented, advises MacDonald. “People need to develop a critical mind, and not just accept the science at face value,” she says. Questions to ask yourself include: How was the research conducted? Was the study conducted by someone with a vested interest in the outcome? “Critical science literacy is more important now than ever before,” says MacDonald.

Unfortunately, the media doesn’t always help clarify the debate. Take, for instance, this excerpt from one of the many news stories about BPA:

Tests performed on liquid baby formula found that they all contained bisphenol A (BPA). This leaching, hormone-mimicking chemical is used by all major baby formula manufacturers in the linings of the metal cans in which baby formula is sold. BPA has been found to cause hyperactivity, reproductive abnormalities, and pediatric brain cancer in lab animals. Increasingly, scientists suspect that BPA might be linked to several medical problems in humans, including breast and testicular cancer.

While the article is factually correct, it commits several errors of omission. By failing to explain the high degree of uncertainty (similar studies reached different conclusions, and scientists had yet to reach any sort of consensus about what the risks might be) the author creates the impression that the risks are far more certain, and dire, than they actually are. Hundreds of articles in dozens of publications followed a similar tack, and before long, the story was shortened, in the public’s mind, to one simple statement: BPA causes cancer.

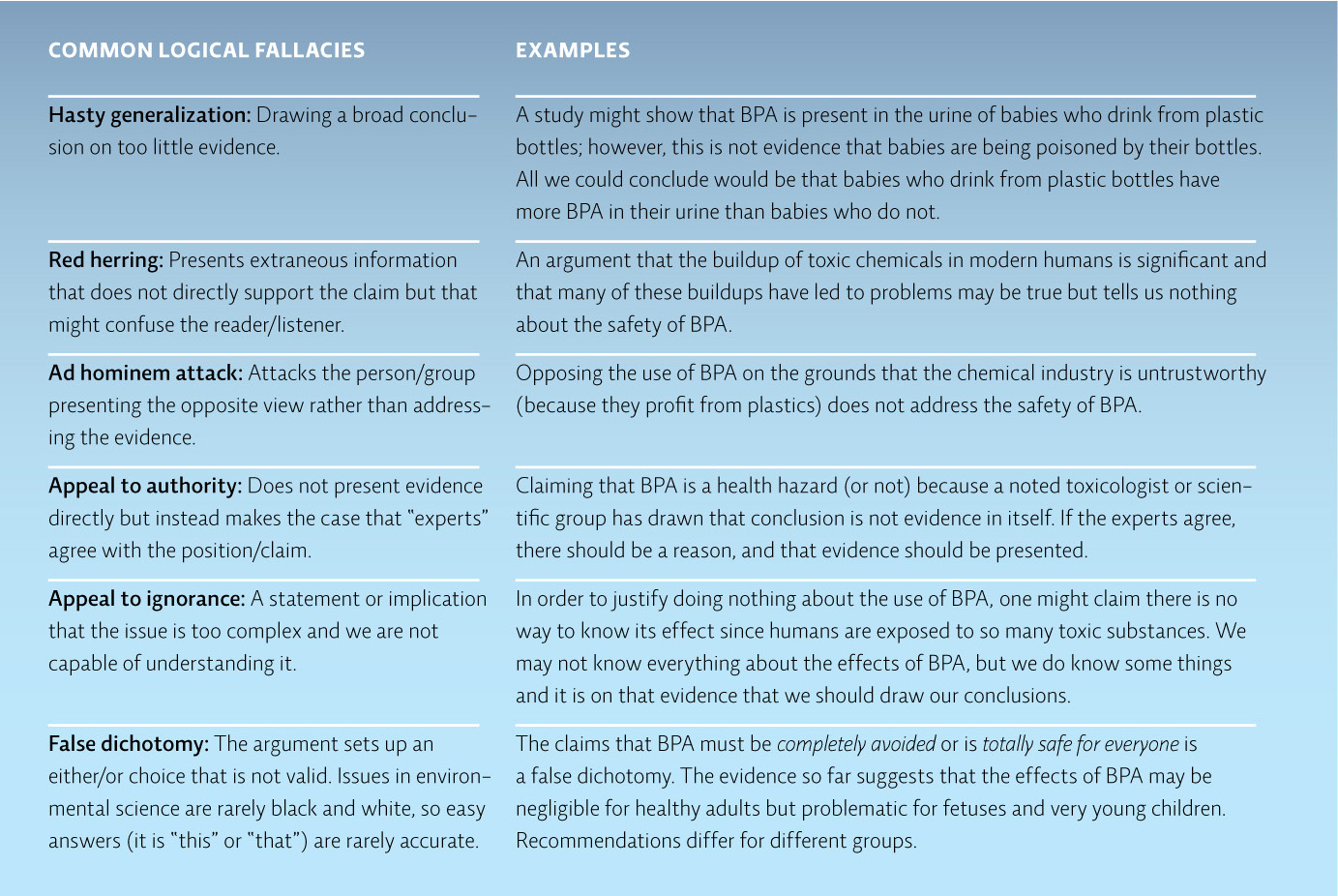

Almost immediately, environmental and consumer groups began calling for a nationwide ban on the chemical. These groups frequently attacked the plastics industry, suggesting that because large, powerful companies profited handsomely from BPA-made products, they had an incentive to downplay or even suppress troubling data. Such attacks often employed logical fallacies and succeeded in stirring up the public’s fears, but told it nothing about whether or not BPA was actually safe. [infographic 3.7]

As a result, average consumers were left to figure out for themselves which side to trust: Were environmental activists and some scientists exaggerating, or was BPA truly dangerous? Why did some scientific studies show deleterious effects from the chemical, while others did not? More importantly, what precautions could, or should, individuals take?

Critical thinking skills are the antidote to logical fallacies; they enable individuals to logically assess and reflect on information and reach their own conclusions about it. The skill set can be broken down into a handful of components.

Be skeptical. Just like a good scientist, one should not accept claims without evidence, even from an expert. This doesn’t mean refusing to believe anything; it simply means requiring evidence before accepting a claim as reasonable. For example, a Science News article, “Receipts a Large and Little-Known Source of BPA,” quoted a researcher as saying that he believed BPA, a common component of the thermal paper of cash register receipts, “penetrated deeply into the skin, perhaps as far as the bloodstream.” The actual research documented the amount of BPA in the receipts and on the surface of fingers that held a receipt, but not the amount of BPA in the bloodstream of individuals who handled the receipts. A skeptical reader would therefore question the inference that BPA from receipts enters the body, since no evidence was presented regarding its uptake, only its presence on the skin’s surface. Perhaps BPA does enter the bloodstream through receipts, but we need evidence in order to view this claim as reasonable.

51

Evaluate the evidence. Is the claim that is being made derived from anecdotal evidence (unscientific observations, usually relayed as secondhand stories) or from scientific studies? If it is based on actual studies, how relevant are those studies to the claim? Were they done on primates? Rodents? Cells in a Petri dish? Or did the researchers look at human populations?

Be open-minded. Try to identify your own biases or preconceived notions (most chemicals are dangerous; most people overreact to things like this, etc.) and be willing to follow the evidence wherever it takes you.

Watch out for biases. Does the author of the study or person making the claim have a position he or she is trying to promote? Is this person financially tied to one conclusion or another? Is he or she trying to use evidence to support a predetermined conclusion?

To try to make sense of some of the conflicting data, Lanphear decided to follow up on some research he heard about in Ottawa. Some toxicologists had mentioned that they’d consistently noted that young rodents exposed to BPA were more anxious than others. So he and his colleagues decided to follow nearly 250 pregnant women, testing their urine for BPA exposures, and then follow their children during the first three years of their lives. In 2012, he and his colleagues published their results in the science journal Pediatrics—97% of mothers and children tested positive for BPA, and the more BPA children were exposed to in the womb, the more they appeared anxious or depressed. The findings—supported by funding from the U.S. government—were particularly true for young girls.

52

In the paper, Lanphear and his team acknowledged that the study was small, and children may have been exposed to other endocrine disruptors that might have influenced the results. This makes it difficult to know the specific effects of BPA. Steven Hentges, a representative of the American Chemistry Council, which represents the chemical industry, told the media in a statement about the paper: “For parents, the most important information from this report is that the authors themselves question its relevance.” This statement, however, misrepresents the authors’ self critique. Most research papers end with caveats about the study’s limitations, and Hentges, who is paid by the industry that profits from selling BPA, cannot be expected to provide an objective perspective.