4.2 Human populations grew slowly at first and then at a much faster rate in recent years.

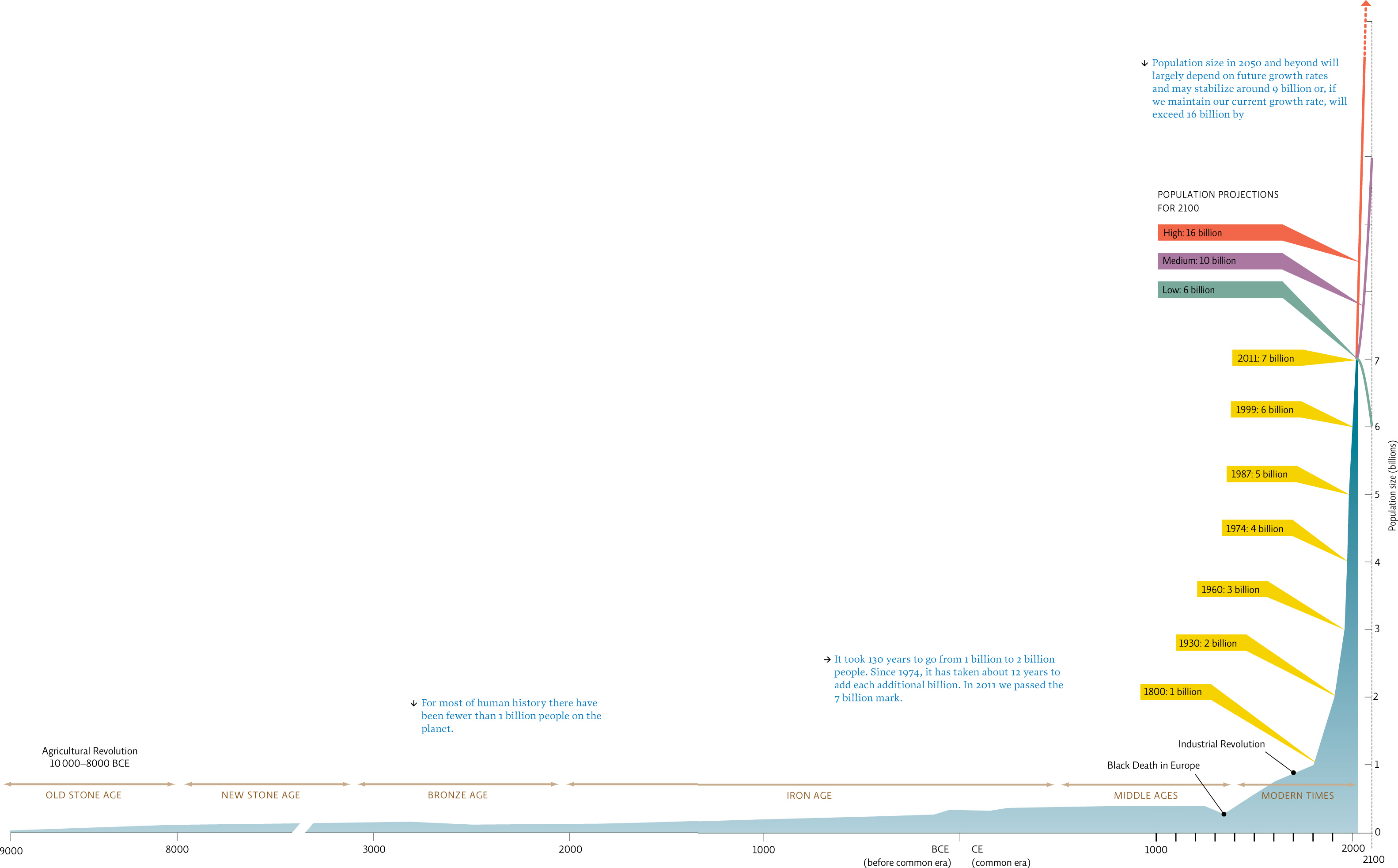

At least twice in the course of human history, global human population has hit a dramatic growth spurt. The first came around 10 000 years ago, when the Agricultural Revolution dramatically increased the amount of food we could grow, and thus the number of mouths we could feed. As more food translated into healthier people, lower death rates, and longer life spans, the growth rate increased and global population raced toward the 100 million mark. The next growth spurt came in the 1700s, when the Industrial Revolution ushered in a rapid succession of advances in both sanitation and health care—including vaccines, cleaner water, and better nutrition. Once again, death rates fell, life expectancy rose, and the population swelled. [infographic 4.1]

In China, this cycle played out most dramatically during the latter half of the 20th century, when the country experienced a spectacular improvement in its standard of living. Between the 1950s and 1970s, life expectancy increased from 45 to 60. But as the crude death rate fell, the crude birth rate held steady. By 1949, China was home to 500 million people—37 times the population of Canada at that time—making it the most populous country on Earth. By 1970, population had swelled to almost 900 million: roughly a quarter of the world’s people crammed onto just 7% of the planet’s arable land.

59

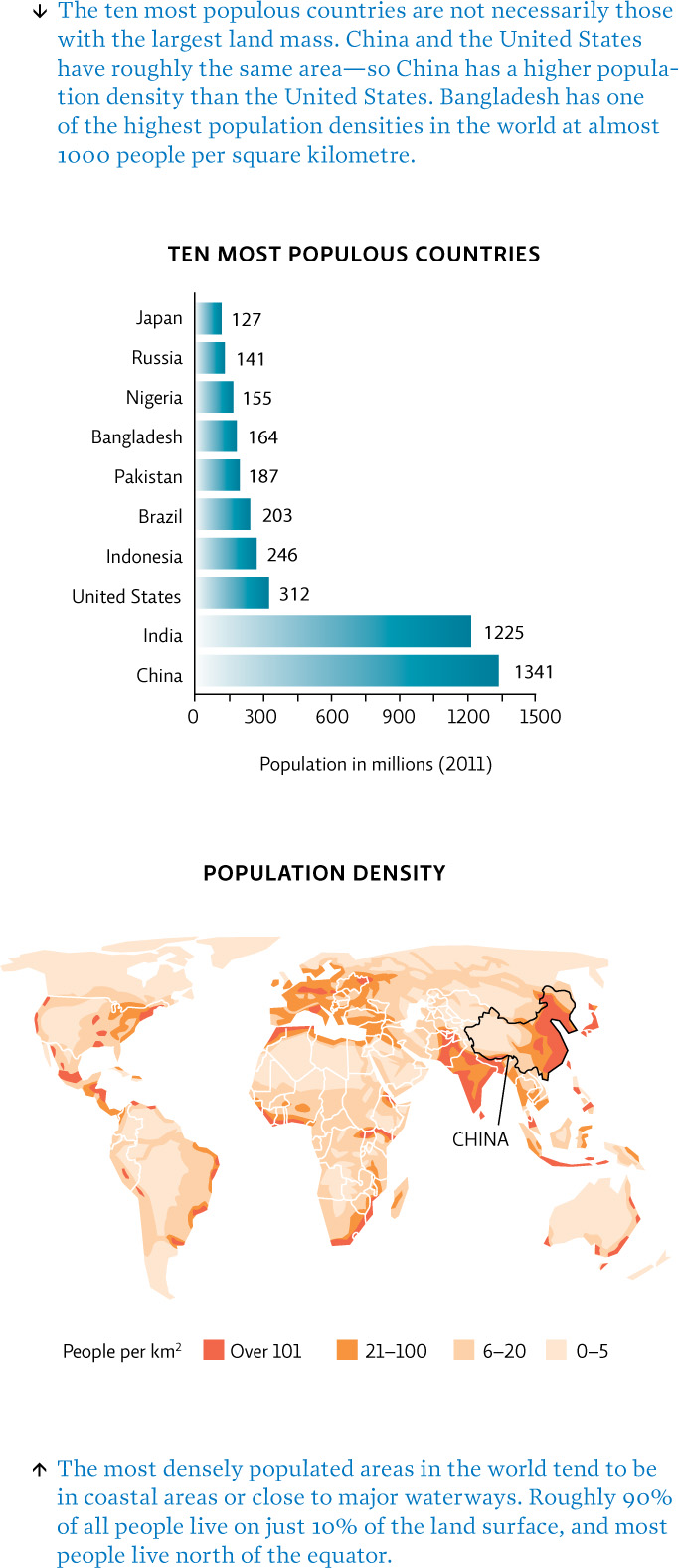

Today, China is the most populous nation, with more than 1.3 billion people, but it will soon be surpassed by India, which is projected to have 1.5 billion by 2030. Like many nations around the world, more and more of China’s people live in big cities, with many urban areas reaching record population densities. [infographic 4.2]

In China, such growth became a political issue. In the late 1950s, a famine claimed 30 million lives; and during the 1970s, a severe shortage in consumer goods—soap, eggs, sugar, and cotton—led to strict rationing. The government blamed the country’s woes on overpopulation. Today, experts say that the real culprit was botched state planning. “China was not unlike other parts of the world at that time, in terms of higher life expectancies and growing population,” says Wang Feng, Director of the Brookings-Tsinghua Center for Public Policy. “We could have managed, as other countries did, with better agricultural and economic policies.”

Maybe so. But in the late 1970s, with two-thirds of the population under the age of 30, and the baby boomers of the 50s and 60s just entering their reproductive years, China’s leaders had good reason to panic. A population with a lot of young women has population momentum; it will continue to increase for another generation, even if each couple only has two children, just enough to replace them when they die. If the government could not feed the mouths it already had, how in the world would it feed any more?

60

So in 1979, the country’s leaders issued a mandatory decree: no family could have more than one child. The government vowed to deny state-funded health care and education to all but the first-born. Parents who didn’t comply also risked losing their jobs and faced severe fines (often several times their annual income) and penalties (including a loss of government subsidies for baby formula and other foodstuffs).

Dramatic as it sounded, the idea of strictly enforced population control was not entirely new. In fact, modern societies have fretted over our swelling ranks as far back as the Industrial Revolution (that second growth spurt); that’s when an English priest by the name of Thomas Malthus first noticed that food supplies were not increasing in tandem with population. Unless something changed, he warned, we would soon have more mouths to feed than food to feed them with. And when that happened, disease, famine, and war would surely follow. According to Susan Greenhalgh, Harvard University anthropologist and author of the book Just One Child: Science and Policy in Deng’s China, such catastrophic thinking was a big part of how the Chinese government arrived at its one-child policy.

When China’s leaders enacted the policy, they promised that the policy would be a short-term one, set to expire in 30 years. By then, they said, Chinese society would have adapted to a small-family culture, and with hundreds of millions of births prevented, the quality of life would have improved substantially.