4.5 The age and gender composition of a population affects its potential for growth.

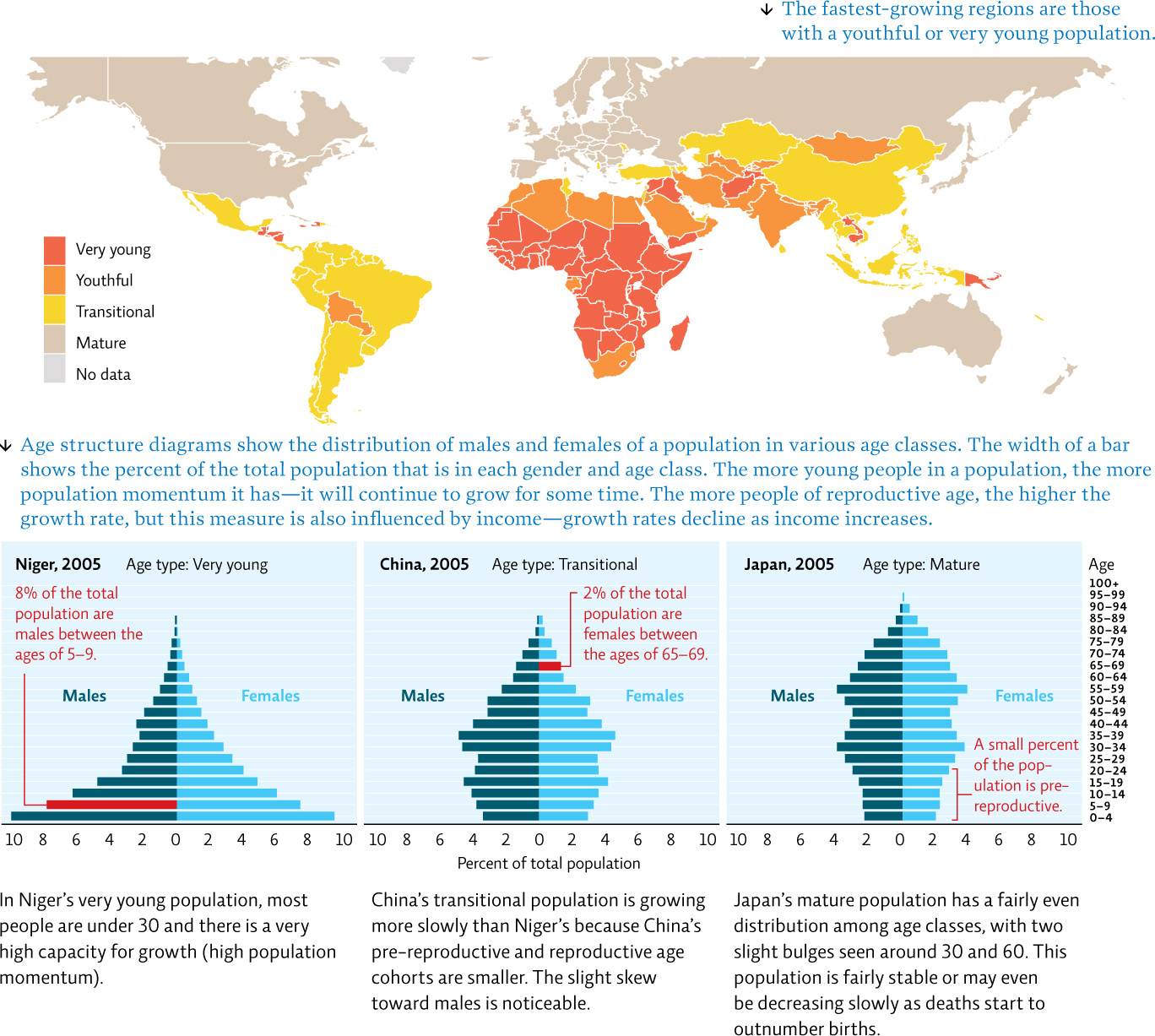

Demographers create a diagram that displays a population’s size as well as its age structure (the percentage of the population that is distributed into various age groups, called cohorts) and sex ratio. These age structure diagrams give insight into the future growth potential of a population. [infographic 4.7]

When the majority of the people in a population are young, the diagram looks very much like a pyramid; there are nearly equal portions of men and women and fewer and fewer people at each higher age group. Because so many people are young, and many have not yet reached reproductive age, the population will continue to grow rapidly over time.

Currently, many industrialized nations—including Canada, the United States, and many European countries—have top-heavy age structure diagrams with many older people. In many cases, the struggle to care for these rapidly aging populations has turned prickly. In 2010, in order to relieve retirement age problems (and thus government pension payouts), France raised the retirement age from 60 to 62, sparking riots throughout the nation. And in 2012, Canada announced that it would gradually increase the age of eligibility for the Old Age Security (OAS) pension and Guaranteed Income Supplement (GIS) from 65 to 67.

68

China’s age structure diagram has lost the bottom-heavy shape, reflective of its changing population age structure. Falling birth rates and rising life expectancy have tipped the balance between old and young. In 1982, just 5% of China’s population was older than 65. In 2004, that percentage had climbed to 7.5; by 2050, it is expected to exceed 15%. These figures are lower than those in most industrialized countries (especially Japan, where the proportion of people over the age of 65 years is 20%). But because elderly people are still dependent on their children for support, this situation could spell disaster.

Demographers call it the 4-2-1 conundrum: as they settle into middle age, the members of each successive generation of only children will find themselves responsible for two aging parents and four grandparents. If that single child fails, family elders would be left with virtually no options—no second children, or nieces and nephews, or even friends and neighbours who could help out, since most other families would be in an equally precarious situation. In a country without an extensive pension program, this prospect has the government especially worried. Although the Chinese government said in 2008 that the policy would remain in effect for another decade, in 2011 they began considering allowing select couples to have a second child.

There’s another problem with China’s evolving age structure: the workforce. Economists predict that between 2010 and 2020, the annual size of the labour force aged 20–24 will shrink by 50%. This is a forecast with global implications. “The deep fertility declines have plunged China into a demographic watershed,” says Feng. “It means the days of cheap, abundant Chinese labour are over.” For countries like Canada, which have come to depend on a steady influx of cheap goods from China, that’s not such good news. But for the only-children of China, it almost certainly means higher wages, better working conditions, and more jobs to choose from in the coming decades.

An out-of-whack age structure isn’t the only unintended consequence of the one-child policy. The sex ratio of men to women has also grown alarmingly high. Almost everywhere in the world, there are slightly more males than females, though this differs according to age; because women tend to live longer, there are more women than men in older age groups. In most industrialized countries, the sex ratio tends to hover close to 1.05. However, in Canada it is on the low side at 0.99. In China, the ratio has soared from 1.06 in 1979 to 1.17 in 2011; in some rural provinces, it’s as high as 1.3. What does that mean in actual numbers? The State Population and Family Planning Commission estimates that come 2020, there will be 30 million more men than women in China.

69

How did this happen?

Like most Asian countries, and many African ones, China has a long tradition of preference for sons. Boys are thought of as being better-suited to the rigours of manual labour that drive China’s rural, and even industrial, economies. As they grow into men, they often become the main financial providers for retired and aging parents. Daughters, on the other hand, are often tasked with housework and the care of younger siblings and aging grandparents, tasks that are unpaid. When they marry, daughters traditionally become part of the groom’s family, and his parents are generally taken better care of than her own.

Sex-selective abortions—terminating a female pregnancy—have been outlawed in China, but most experts say they are still common, thanks in large part to private-sector health care and the ability of a growing number of Chinese citizens to pay the high cost of a gender-determining ultrasound.

“The deep fertility declines have plunged China into a demographic watershed.”–Wang Feng

A recent study by Chinese researchers from Zhejiang Normal University shows that the sex ratio is high (favouring males) in urban areas where only one child is allowed but in rural areas where a second child is allowed, if the first is a girl, sex ratios are even higher for the second child—as high as 160 males for every 100 females. The researchers attribute this high male bias to sex-selective abortion. Although most demographers agree that outright infanticide is increasingly rare, subtler forms of gendercide—the systematic killing of a specific gender—are known to occur. If a female infant falls ill, for example, she might be treated less aggressively than a male infant would be.

These days, however, it is much more common for girl babies to be put up for adoption. Officially registered adoptions increased 30-fold, from about 2000 in 1992 to 55 000 in 2001. According to a 2012 Globe and Mail article, Chinese adoptions in Canada reached a maximum in 1998, with about 900 adoptions, likely due to a high availability of infants from Chinese adoption agencies. Even though Canadian restrictions on international adoption have increased since then, in 2007, 655 of Canada’s 1710 international adoptions were still from China. Almost all children adopted from China continue to be female.

The result of this skewed sex ratio, 30 years out, seems to be lots of prospective husbands in want of wives. Recent census data shows that in a growing portion of rural Chinese provinces, one in four men are still single at 40. “The marriage market is already getting more intense and competitive,” says Feng. “Men of lower social ranks—who make up a very significant chunk of the population—are being left out. And it’s only going to get worse.”

A growing number of social scientists say that the dearth of women will ultimately threaten the country’s very stability. Experts worry that such large numbers of young men who can’t find partners will prove a recipe for disaster. “The scarcity of females has resulted in kidnapping and trafficking of women for marriage and increased numbers of commercial sex workers,” writes Therese Hesketh, “with a potential rise in human immunodeficiency virus infection and other sexually transmitted diseases.”