5.2 Businesses and individuals impact the environment with their economic decisions.

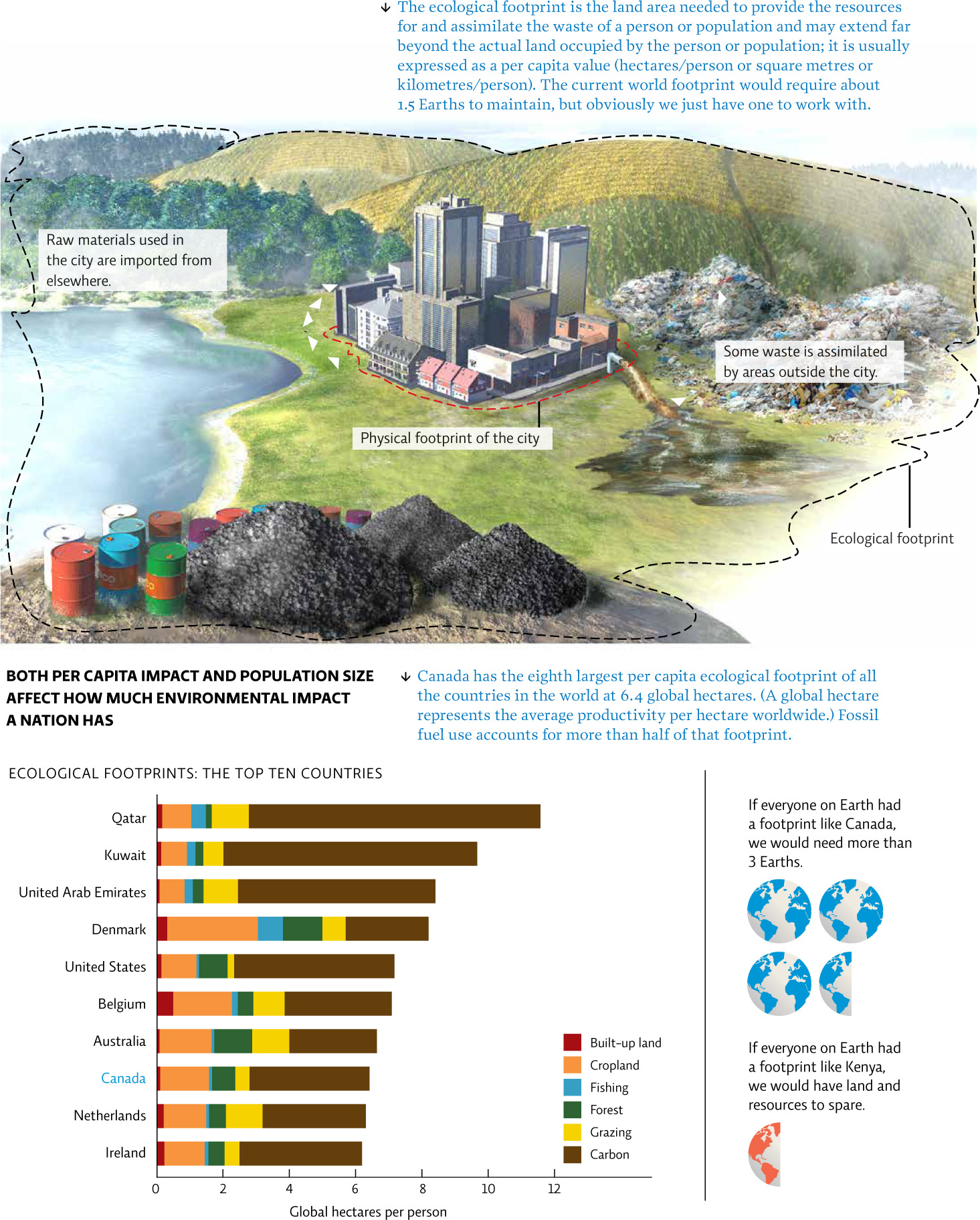

Every business—including Interface and MEC—has an ecological footprint, that is, the land needed to provide its resources and assimilate its waste (typically expressed as hectares (ha) or square metres (m2) per person or population). Ecological footprint is a value that businesses, individuals, and populations use to quantify their impact on the environment. Just as petroleum is needed to make synthetic carpet, MEC uses petroleum as a raw material for some of its fabrics. The company also depends on energy to manufacture and sell its goods—even a simple cotton T-shirt requires farming of cotton, mechanics to gin and spin it, dyes to colour it, then fuel to ship it to factories and, finally, a retail store. [infographic 5.2]

Canada has a particularly high per capita (per person) footprint, in that it requires much more land area to support each person than Canada actually possesses. In fact, if the 7 billion people who populate the planet all lived like the average Canadian, we would need the landmass of 3 1/2 Earths to sustain everyone. According to the World Wildlife Fund’s 2012 Living Planet Report, humans currently use 50% more resources than is ultimately sustainable. This means it would take 1.5 years to replenish what we take in a single year—a clearly unsustainable course.

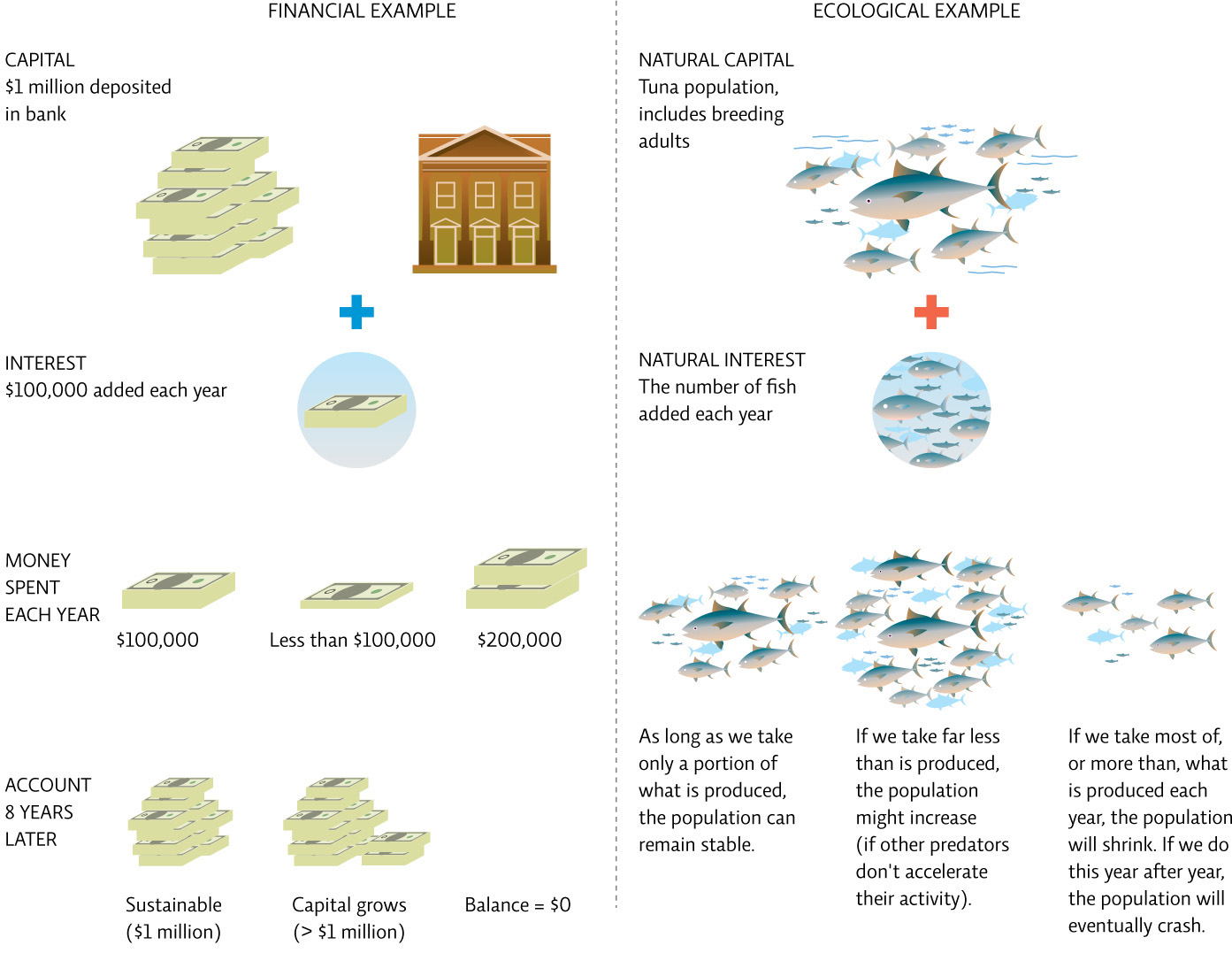

What kinds of essential resources does Earth provide us? Considered in financial terms, our natural capital includes the natural resources we consume, like oxygen, trees, and fish, as well as the natural systems—forests, wetlands, and oceans—that produce some of these resources. Our natural interest is what is produced from this capital, over time, just like the interest you earn with a bank account. Natural interest might be represented by an increase in a fish population, for instance, or new growth in a forest—basically, the extra that is added in a given time frame. [infographic 5.3]

If we only withdraw resources equivalent to (or less than) the natural interest, we will leave behind enough natural capital to replace what we took. We would be operating within our ecosystem’s biocapacity, or its ability to produce resources and assimilate our waste. But by continually taking more than the equivalent of natural interest, we diminish resources and can potentially eliminate them. This can be an especially big problem with commonly held resources like water: once we remove it from wells or rivers, we have to wait for the next rainfall to replenish it. When many users are accessing the resource, it can quickly become depleted or degraded if they do not work together to manage it—a tragedy of the commons (see Chapter 1).

When we dip into our natural capital as humans are doing today, we are decreasing future interest potential. Essentially, we are taking resources away from the future, in what eco-architect Bill McDonough calls intergenerational tyranny. By liquidating our natural capital more quickly than it can be replaced and calling that “income,” the question becomes this: where will future income come from?

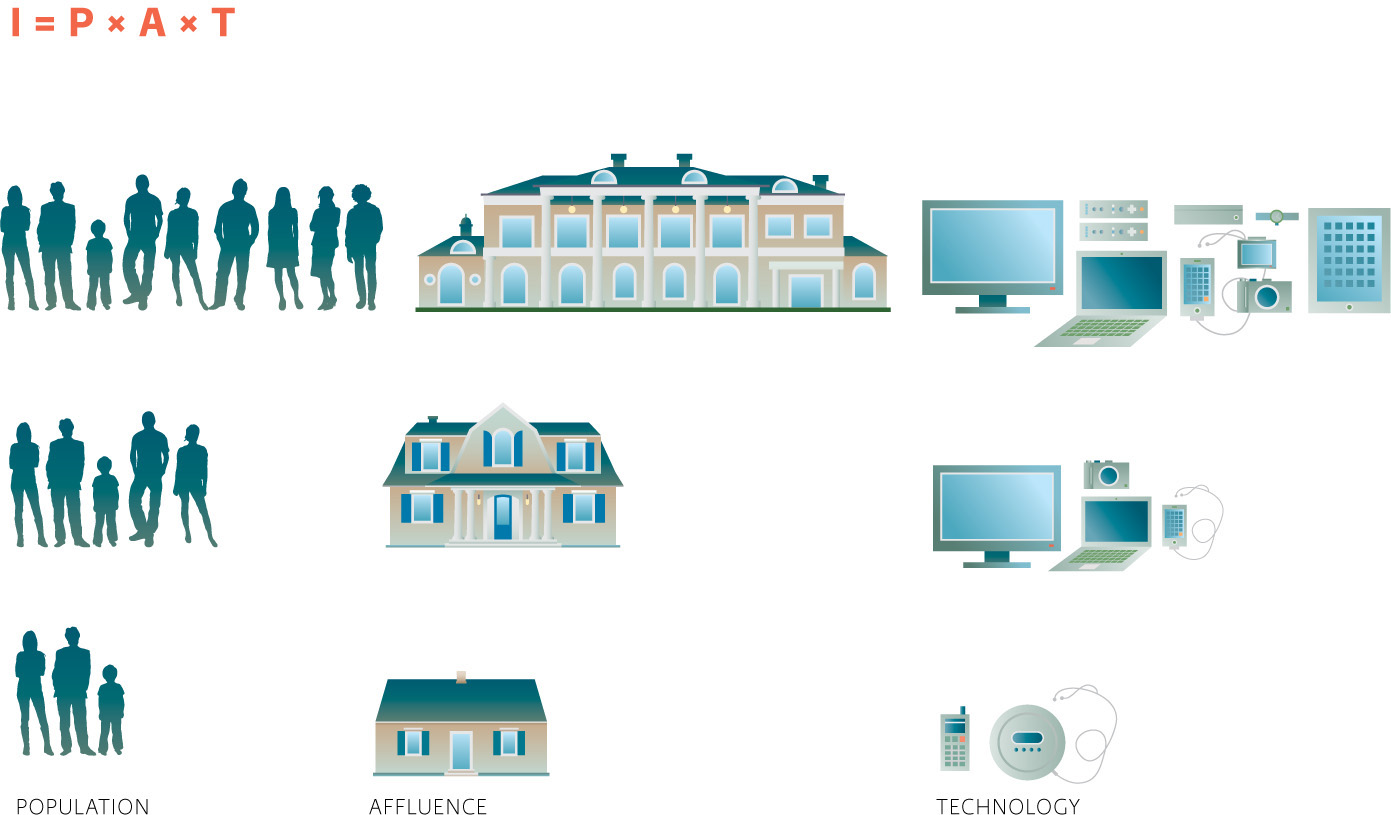

Researchers often use the IPAT model to estimate the size of a population’s ecological footprint, or impact (I), based on three factors: population (P), affluence (A), and technology (T). The premise is that as population size increases, so does impact. More affluent and technology-dependent populations use more resources and generate more waste than do less affluent and technology-dependent populations (technology allows us to build more things, dig deeper, and fly higher, all of which drain the environment). [infographic 5.4]

One caveat with regard to this model is that the right kind of technology can have the opposite effect: it can decrease, rather than increase, environmental impact. In 2006, for instance, after deciding to become sustainable, Interface invented a new technology called TacTiles—small squares of adhesive tape that join carpet tiles together. In contrast with traditional “spread on the floor” adhesives, Interface’s new tape has a 90% smaller environmental footprint, and does not contain any volatile organic compounds, a group of chemicals that Environment Canada recognizes as a health risk. TacTiles also make it possible for customers to replace single carpet tiles easily, when, for instance, there has been a spill. When technologies such as TacTiles reduce the environmental footprint rather than increase it, the equation used to describe their impact changes to: I = (P × A)/T.

80

In 2007, to further reduce its impact, Interface launched a carpet-recycling initiative called ReEntry 2.0. More than 2 billion metric tons of carpet are pulled up and discarded globally each year, and less than 5% of that has historically been reused or recycled. With ReEntry 2.0, Interface developed a way to recycle carpets—both its own and those made by its competitors—to make new carpet, keeping more than 90 000 metric tons of material out of landfills. Interface has promised to eliminate any negative impact it has on the environment by 2020, in a plan it calls “Mission Zero.”

81

Zero waste is also the ultimate goal for MEC, which in 2007 diverted 92% of its waste by recycling, donating, or composting it. Sometimes this requires creative thinking—in the Edmonton store, for instance, the staff turned old packaging into notebooks. These initiatives are not just smart for the planet, they’re smart for the purse—sending 1 metric ton of waste to a landfill costs $325 in disposal charges, while recycling it runs an average of only $68.