5.3 Mainstream economics supports some actions that are not sustainable.

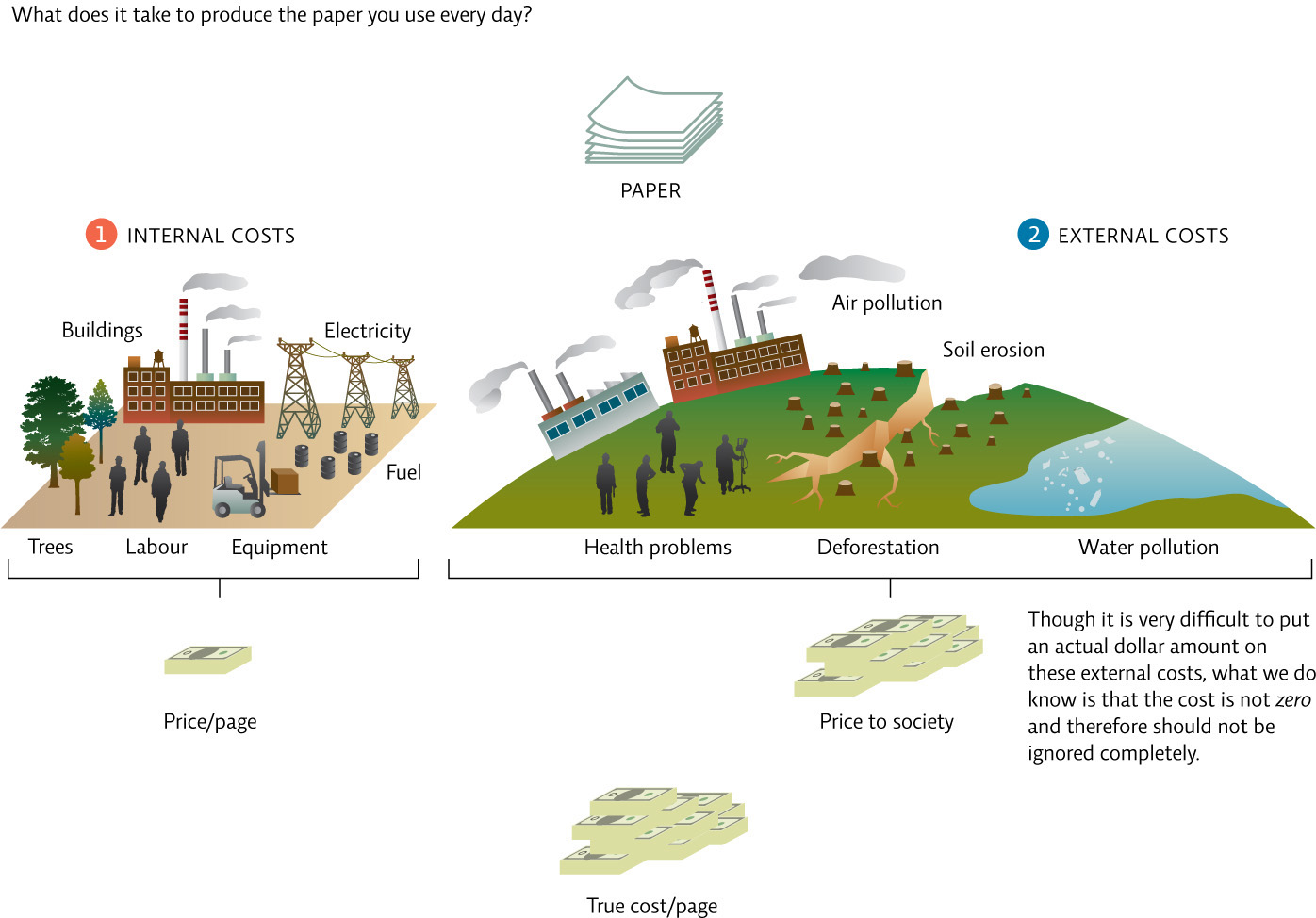

One of the limitations of mainstream economics is that it doesn’t take into account all potential costs. For instance, a carpet tile might require a certain amount of material that has a particular monetary cost—but what about the environmental costs associated with drilling enough oil to make that material in the first place, or the costs associated with cleaning up the pollution it creates? The direct cost of the material is an internal cost—a cost that is accounted for when a product or service is priced—but it is often incomplete. There are also external costs, such as the health costs associated with the waste produced by making the carpet tiles, the use of chemicals to dye textiles, or the environmental damage caused by pollution. Historically, economists have regarded these as external to the business cost (the business doesn’t pay for them) and they aren’t reflected in the price the consumer pays for the good or service. But if the business doesn’t pay for the costs or pass those costs on to the consumer, who does pay? Other people, present and future, and other species do. They pay in the form of degraded health, ecosystems, or opportunities.

An assessment of the cost of a good or service should include more than just the economic costs but also the social and environmental costs—the triple-bottom line. By ignoring the external costs, economies create a false idea of the true and complete costs of particular choices. To pay the true cost of a product or service, the external costs must be internalized. For example, a customer may pay $8 for every 50 square centimetre carpet tile, but the true cost for that piece of carpet would be much higher if it included the cost of greenhouse gas emissions and, for instance, the cost of treating people for asthma who might fall ill as a result of the particulate matter released during the carpet’s production. The inadequate valuation of a product could eventually lead to the exploitation or overuse of resources needed to produce it, an example of market failure.

82

Because we are so accustomed to not paying true costs, we would most likely be appalled at how much goods and services would really cost if all externalities were internalized. Although it sounds discouraging, any time we purchase products that were made in a more environmentally or socially sound manner, we come a little closer to bearing the consequences of our choices. We also create a demand for these products in the marketplace. [infographic 5.5]

Mainstream economics also assumes that natural and human resources are either infinite or that substitutes can be found if needed. While this may be true for some, it is probably not true for all resources. For instance, fossil fuels are finite and will run out, even with technological advances that allow us to access more of the fuel that is left. It remains to be seen whether or not we can replace fossil fuels with sustainable alternatives at current levels of use. Additionally, our actions can degrade air and water resources faster than nature can restore them; crop productivity also has its limits.

Another assumption of mainstream economic theory is that economic growth can go on forever. But, since there are inherent limits to what Earth can provide, unlimited resource-based growth is not, in fact, possible. We have to work within the limits of available resources in ways that allow essential ecosystem services to continue.

83

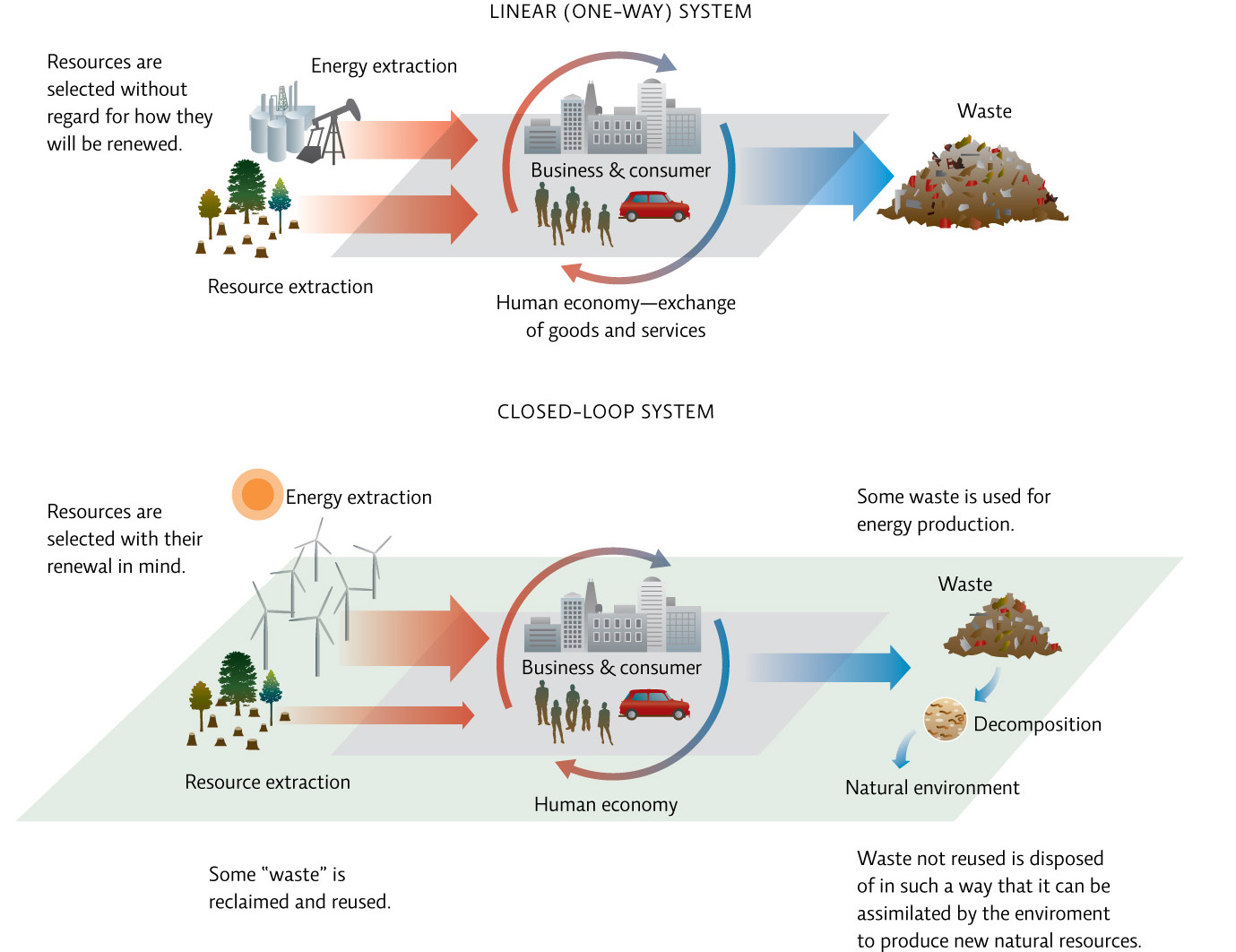

Most models of production follow a linear sequence: raw materials come in, humans transform those materials into some kind of product, and then they discard the waste generated in the process. Eventually the product itself becomes waste. But because some resources are finite—and waste in the form of pollution can damage natural capital like air, water, and soil—linear models of production will eventually fail. Even though only 8% of MEC’s waste ends up in landfills, it adds up to 70 metric tons per year. So MEC conducts an annual waste audit for each facility to try to reduce waste even further, looking at both volume and contents. As the company says, they go “dumpster diving,” periodically retrieving items from their own dumpsters and determining what and how much is going in the garbage and whether it could be diverted to recycling bins or composting initiatives.

Even better, Interface’s ReEntry 2.0 program uses old carpet tiles to make new ones, and old carpet backings to make new carpet backings, in an effort to make the production process more cyclical. This is an example of a closed-loop system, in which the product is returned into the resource stream when consumers are finished with it, or is disposed of in such a way that nature can decompose it. By leasing carpet rather than selling it, Interface manages its product in a cradle-to-cradle fashion—the carpet needs to be durable and recyclable, because Interface is responsible for the impact of its use at every stage of the process. (See the diagram that opens this chapter on pages 74–75.) [infographic 5.6]

Another problem with traditional economics is that it discounts future value: it tends to give more weight to short-term benefits and costs than it does long-term ones. In other words, something that benefits or harms us today is usually considered more important than something that might do so tomorrow. For instance, we value the tuna we can harvest today more highly than tuna we might harvest 10 years from now, so the value of taking a large harvest of tuna today seems to outweigh the benefits of taking less now to ensure there is still some later. If the money we could earn by using the resource now is more than that possible by sustainably harvesting, modern economics tells us it is more profitable to use it now and invest the resulting money in another venture. But how might the loss of tuna affect the ecosystem and other populations? And what about that “other venture”? Will there always be another fish population to harvest?

Energy usage must also be considered in a company’s quest for sustainability. Thirty percent of Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions come from the energy used to construct and maintain buildings. Since the 1980s, MEC has adopted an “aggressive green building vision,” says Labistour, to cut down on the energy, water, and materials used in its retail buildings. For instance, the retail site in Winnipeg—dubbed by industry experts the most energy-efficient outlet in the country, according to MEC—has a structure made entirely of reclaimed materials, thus keeping these materials out of landfills. Extra insulation and double (or even triple) paned windows keep the indoor climate comfortable. Furthermore, lining the roof with vegetation to create a “green roof” provides cooling in summer, as water evaporates from the soil, and extra insulation in the winter. The roof vegetation is fed by a composting toilet, which also cuts down waste water by 50%. This store and the company’s Ottawa retail location were the first two retail buildings in Canada to comply with the C2000 Green Building Standards that require facilities to use 50% less energy than conventional structures.

A sustainable approach would be more cyclical, where “waste” becomes a raw material once again and can be used to make products.

Interface has also maximized energy efficiency in its facilities, installing skylights and solar tubes to replace artificial, electricity-dependent lighting, and using more energy-efficient heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems. In one of its factories, Interface also installed a real-time energy tracker that displays energy use prominently for its employees to see, inspiring them to think of new ways to conserve energy. These and other changes enabled the company to cut the amount of energy it derived from fossil fuels by 55%, and reduce its total energy use by 43%.

Ecologically minded economists are considering how to incorporate environmental considerations into economic decisions. Ecological economics is a discipline that considers the long-term impact of our choices on human society and the environment. These economists support actions such as improving technology to increase production efficiency and reduce waste; valuing resources as realistically as possible; moving away from dependence on nonrenewable resources; and shifting away from a product-oriented economy. They look to natural ecosystems as models for how to efficiently use resources and live within the limits of nature. But, ecological economists feel that our ingenuity will only take us so far and that economic growth does have limits; therefore, we must significantly change the way we do things in order to become sustainable as a society.

84