5.4 There are tactics for achieving sustainability.

Since 1994, Interface has reduced greenhouse gas emissions from its manufacturing facilities by 35%, and now relies on recycled or bio-based ingredients for 40% of its raw materials. This drive toward sustainability has not hurt profits: over the same time period, the company has increased sales by two-thirds and doubled its earnings.

Running a green business—doing business in a way that is good for people and the environment—is also profitable for MEC. In 2011, the company emitted 46% less greenhouse gases from facilities than it did in 2007 while also reporting $270 million in sales, a nearly $10 million increase from the year before.

85

The ultimate goal is to run a fully sustainable business, with zero waste and no extra greenhouse gases. By definition, sustainable development must meet present needs without preventing future generations from meeting their needs. Anderson vowed in 1994 that Interface Carpet would become the world’s first sustainable business. Despite these ambitions, no business has yet succeeded in this goal. “We’re not there yet,” says MEC’s Labistour. “It’s a journey.”

How does a company find inspiration on how to become sustainable? One way is to look to natural ecosystems—a perfect example of sustainable resource use and waste minimization—and engage in biomimicry (see Chapter 1). For instance, a new fabric named Greenshield is modelled after a lotus leaf (Nelumbo nucifera), one of the most water-repellent structures in nature. Like the leaves, the fabric contains tiny crevices that trap air, so water droplets (and attached dirt) roll off easily, making it as stainand water-resistant as conventional fabrics, but using a significantly smaller amount of harmful chemicals.

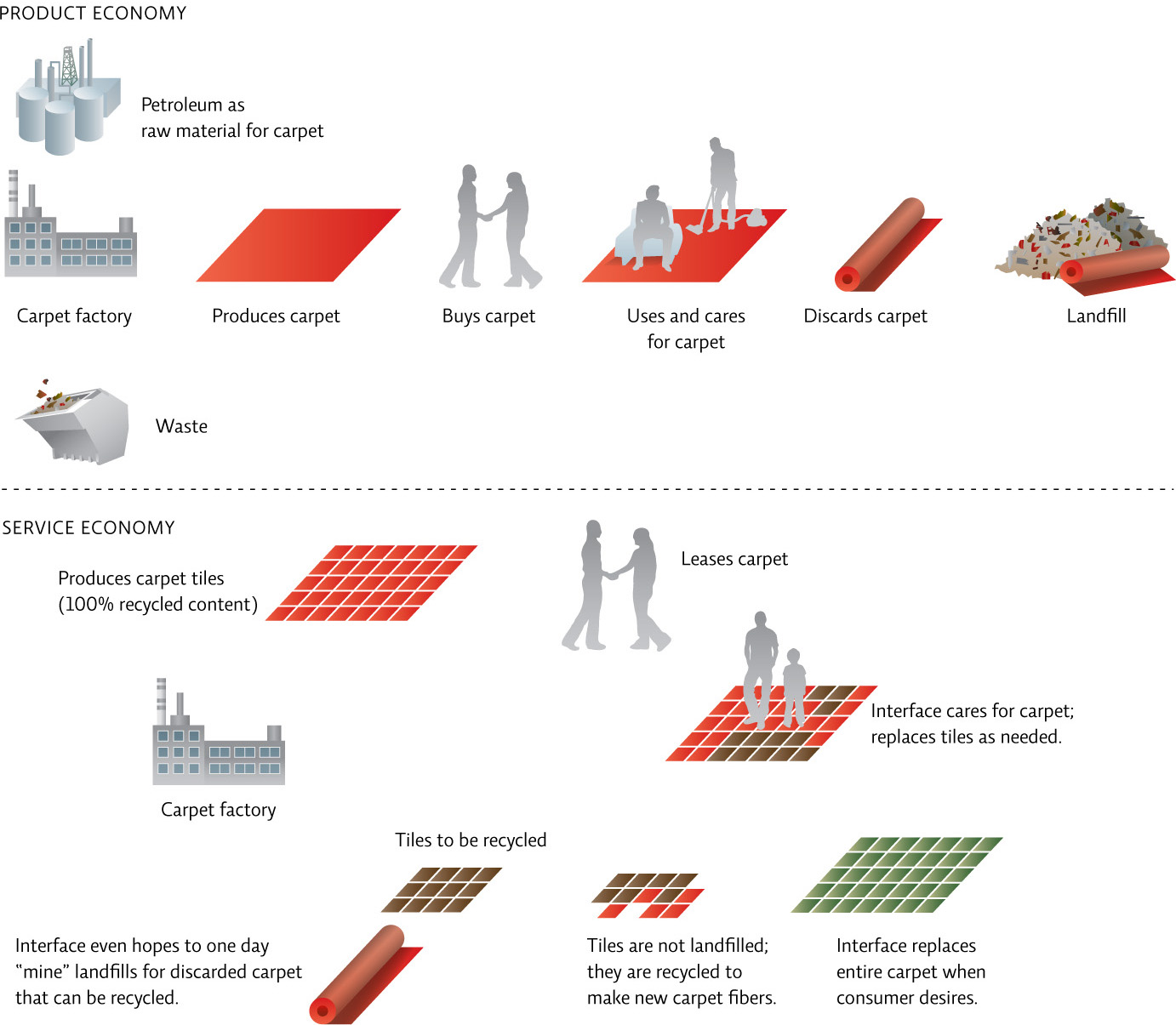

At Interface, Anderson was strongly inspired by biomimicry. For instance, the TacTiles technology that the company developed to replace glue was based on the physics that explains how a gecko lizard clings to walls and ceilings. The microscopic hairs on a gecko’s foot bond to the molecular layer of water that is present on nearly every surface, allowing its feet to cling. Interface used this information to develop tiles that bond to one another rather than to the floor, making a kind of “floating” carpet that stays in place due to gravity rather than being actually glued to the floor. This makes carpet installation and removal much faster and easier. Interface also revolutionized its operations by considering itself part of a serviceeconomy; it focuses on selling a service rather than a product. Customers “lease” the carpet; Interface maintains it and replaces it as needed. This encourages Interface to produce carpet that is durable and recyclable and also easily replaceable. [infographic 5.7]

Another sustainable business practice involves take-back programs, particularly for products with a defined lifespan, such as electronics: customers return the product to the producer when they are finished or when they need an upgrade. This provides an incentive to the producer to make a durable, high-quality product that can be reused or recycled.

Changing the way we do business is not going to be easy. Start-up or upgrade costs can be substantial, and even though they may pay for themselves in the long run, many businesses simply do not have the capital to fund the improvements. Plus, they may find themselves at a competitive disadvantage with businesses that are not trying to internalize costs. Although MEC wanted to “green” all of its retail buildings, it simply couldn’t afford to make all of the changes it wanted to at those facilities that were leased, rather than purchased. “We had to prioritize which energy upgrades to do,” says Labistour. “These were tough choices.”

Consumers also have a role to play. We can all decrease our impact by making more sustainable choices and by consuming less. Thinking about sustainability doesn’t necessarily mean “doing without,” but it does mean being mindful of our choices and opting for sustainable or low-impact choices whenever possible.

Share programs are a useful option for items that people need infrequently, such as a car, bicycle, or power tool for those who live in a large city. Rather than buying, owning, and then storing the product for a large part of the time, consumers buy memberships in a sharing company and only use the product when they need it.

When we need to purchase something, it’s important to consider the item’s true cost. Recycled paper often costs more, but that higher cost may more closely reflect the true cost of paper. But if consumers are not willing to put their buying dollars behind their environmental ideals, businesses that make and sell paper from trees will still be more successful. Knowing a product’s true cost requires transparency from the industries that produce and sell us goods and services. That is hard to come by, often because the businesses themselves don’t know all the external costs associated with their products. In other words, it will take changes by both consumers and producers to put business and industry on the path to sustainability. But there are things that can be done to level the playing field.

Governments can encourage sustainability by providing incentives for businesses to account for true costs rather than just internal costs. This could be accomplished by taxing companies based on how much pollution they generate, subsidizing environmentally friendly processes, or giving out pollution “permits” that companies could sell if they release less pollution than they are allowed (cap-and-trade—see Chapter 21). For instance, if there is a pollution tax, it will be passed on to the consumer, who then decides whether or not to buy the product. The manufacturer that minimizes waste production and relies on fewer fossil fuels than its competitors might be able to meet the regulations at the lowest cost, have lower prices, and as a result, have a major market advantage. While promising, these policies can be complex to implement, because external costs are hard to quantify (How is a pollution tax fairly assessed?), and because they may put a burden on smaller manufacturers who have less ability to absorb the cost of upgrades; passing these costs on to the consumer also stresses low-income households.

86

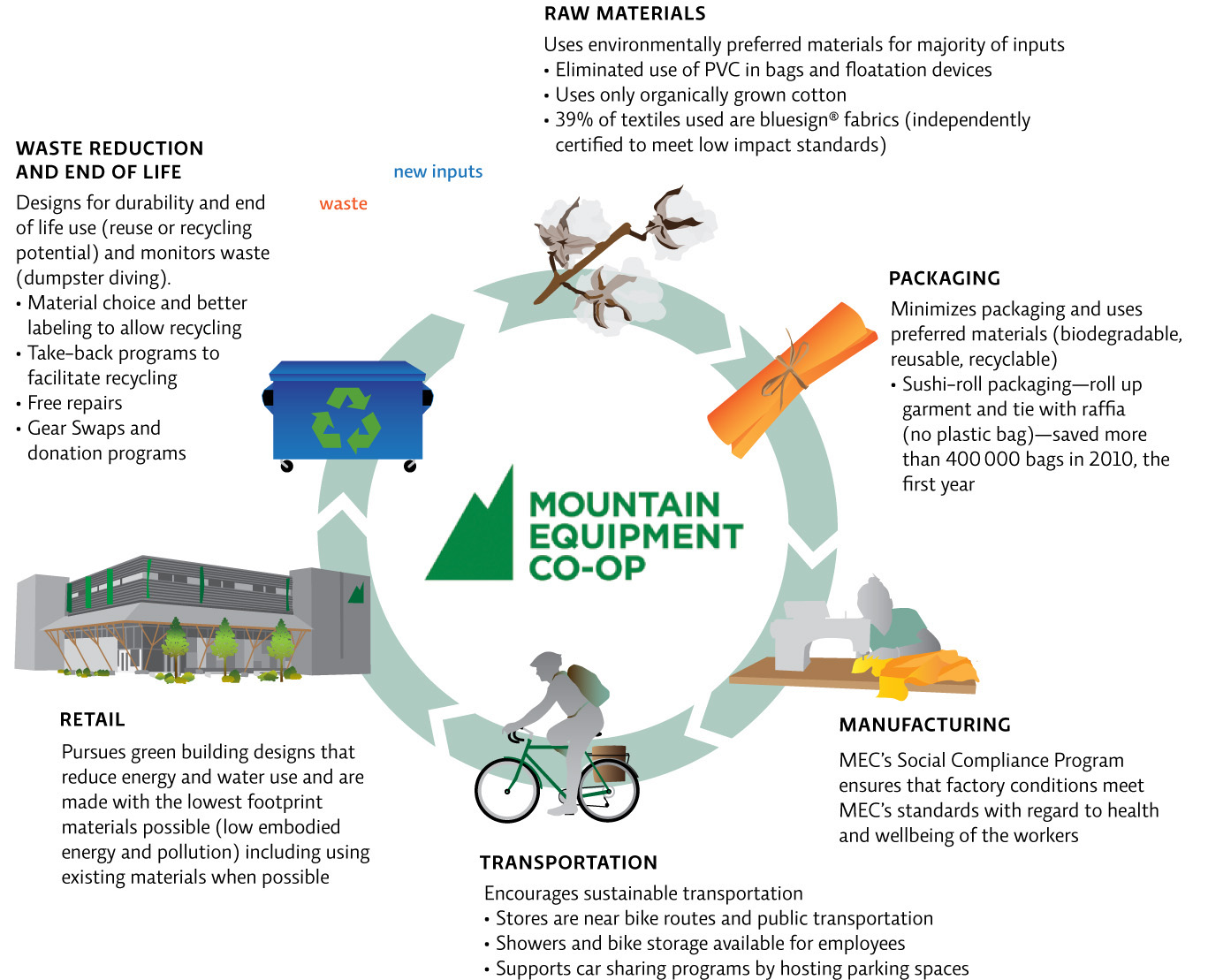

To MEC, being sustainable is not just about cleaning up the environmental damage it creates—it’s about finding ways to conduct business without causing environmental damage in the first place. A company that adopts cradle-to-cradle resource management is responsible for the resource or the impact of its use at every stage of the process. It can do this by considering not just the immediate impact of using a product but also the upstream and downstream impacts—a life-cycle analysis. This can lead to better material choices (less toxic, more sustainable) and better process choices (reusable materials, less waste and pollution). “We’re trying to understand the system that creates damage—from the chemicals, manufacturing process, to packaging—to understand where our organizational impacts lie,” says Labistour. MEC is now collaborating with similar businesses to establish common environmental standards they all follow, such as best practices to reduce the use of hazardous chemicals to make textiles. The company is also a supporter of bluesign®, an independent auditor of textile mills that helps facilities reduce their harm to the environment. [infographic 5.8]

87

88

One way to communicate lifecycle information is through ecolabelling. At MEC, a signature symbol indicates that materials include at least 50% organic cotton or recycled polyester, and are free of polyvinyl chloride (PVC), which is hazardous to produce and is difficult to recycle. But consumers have to be wary of labels because as “green” products become more attractive to consumers, more companies engage in greenwashing—claiming environmental benefits for a product when they are minor or nonexistent. Fair trade items are, however, more likely to be sustainably produced. In addition, for a product to be considered fair trade, workers must be paid a fair wage and work in reasonable conditions to produce the goods or services.

In June 2011, Interface began producing its first 100% non-virgin fibre carpet tiles, made from reclaimed carpet, fibre derived from salvaged commercial fishnets, and post-industrial waste. It remains the world’s leading manufacturer of commercial carpet tiles. “I think we’re on the right track and we’ll keep on going,” says Anderson, who stepped down as the company’s CEO in 2001 but still played the role of the company’s conscience until his death in 2011 at the age of 77. “We’ll get to the top of that mountain.”

It’s easy to wonder why companies would go to so much trouble to reduce their environmental impact, when competitors who avoid the time and effort may be able to offer the same goods at lower prices. But to Labistour, reducing waste and pollution isn’t just good for the environment—it’s good for business. As an outdoor equipment company, MEC needs healthy ecosystems for co-op members to enjoy its products, he says. And resources are already becoming scarce, he adds, so companies have to learn to use them wisely so that they can continue operating when shortages occur. “It’s only a matter of time before every organization is going to have to pay far more attention to the social and environmental contexts in which they operate,” says Labistour. “We focus on sustainability so the company can continue operating as it is.” The fact that this focus also helps preserve natural resources for future generations is a huge bonus, he adds. “The reason I am doing these things is both for the future of my organization, and my children.”

89

Select references in this chapter:

Constanza, R., et al. 1997. Nature, 387: 253–260.

World Wildlife Fund. 2012. 2012 Living Planet Report [Online], wwf.panda.org/about_our_earth/all_publications/living_planet_report/2012_lpr/.

BRING IT HOME: PERSONAL CHOICES THAT HELP

You have an impact on creating a sustainable society. Every time you buy a product or service, you are telling the manufacturer that you agree with the principles behind the product. You can use your purchasing power to show companies that people are interested in quality products that support environmental and social values.

Individual Steps

Reduce the amount of stuff you accumulate by buying fewer items and by choosing products that are well made and last longer.

Reduce the amount of stuff you accumulate by buying fewer items and by choosing products that are well made and last longer.

Use the Good Guide app on your smartphone to scan product bar codes and see how the products rank on different scales of environmental impact, social responsibility, and health.

Use the Good Guide app on your smartphone to scan product bar codes and see how the products rank on different scales of environmental impact, social responsibility, and health.

Ask your local food store or pharmacy to stock fair trade certified products if they don’t already.

Ask your local food store or pharmacy to stock fair trade certified products if they don’t already.

Instead of buying a new or used car, join a car-share program like Zipcar.

Instead of buying a new or used car, join a car-share program like Zipcar.

Group Action

Get together with family and friends and write a letter to your favourite companies, asking them to reduce their ecological footprint. You can ask them to become more transparent by publishing how their business practices impact the environment.

Get together with family and friends and write a letter to your favourite companies, asking them to reduce their ecological footprint. You can ask them to become more transparent by publishing how their business practices impact the environment.

Policy Change

Start a blog or Facebook page to chronicle the changes you make in your buying habits and encourage others to do the same. Discuss the companies whose environmental policies you agree with.

Start a blog or Facebook page to chronicle the changes you make in your buying habits and encourage others to do the same. Discuss the companies whose environmental policies you agree with.

90