6.2 Organisms and their habitats form complex systems.

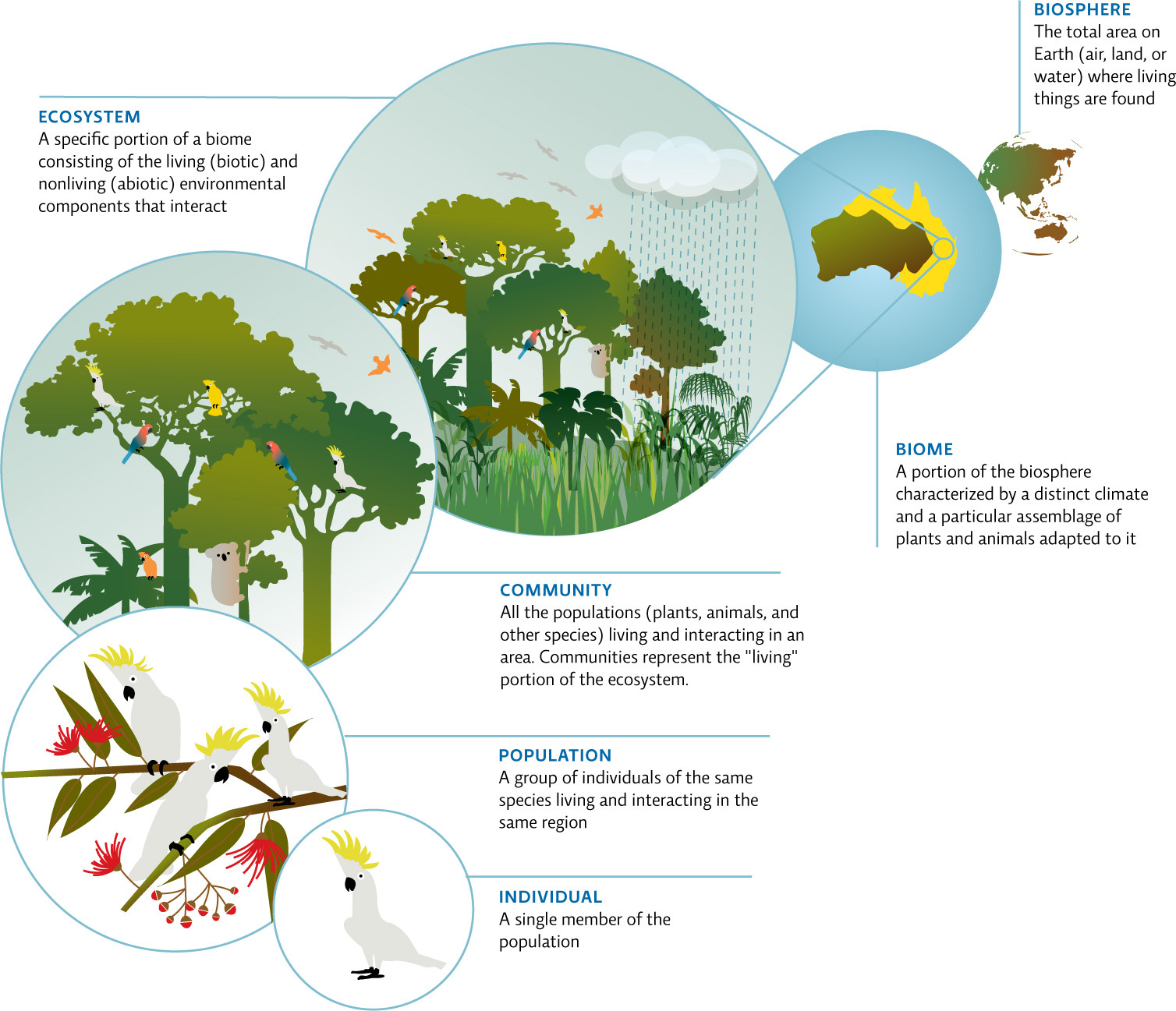

The term biosphere refers to the total area on Earth where living things are found—the sum total of all its ecosystems. An ecosystem includes all the organisms in a given area plus the nonliving components of the physical environment in which they interact. This physical environment is often referred to as an organism’s habitat. Ecologists study how ecosystems function by focusing on species’ interactions with their surroundings and with other species in their communities. They also study interactions between members of the same species within a population. Individuals of each species in a community occupy a specific ecological niche shared by no other species in that community. In the natural world, ecosystems assume a range of shapes and sizes—a single, simple tide pool qualifies as an ecosystem; so does the entire Mojave Desert. [infographic 6.1, 6.2]

95

96

97

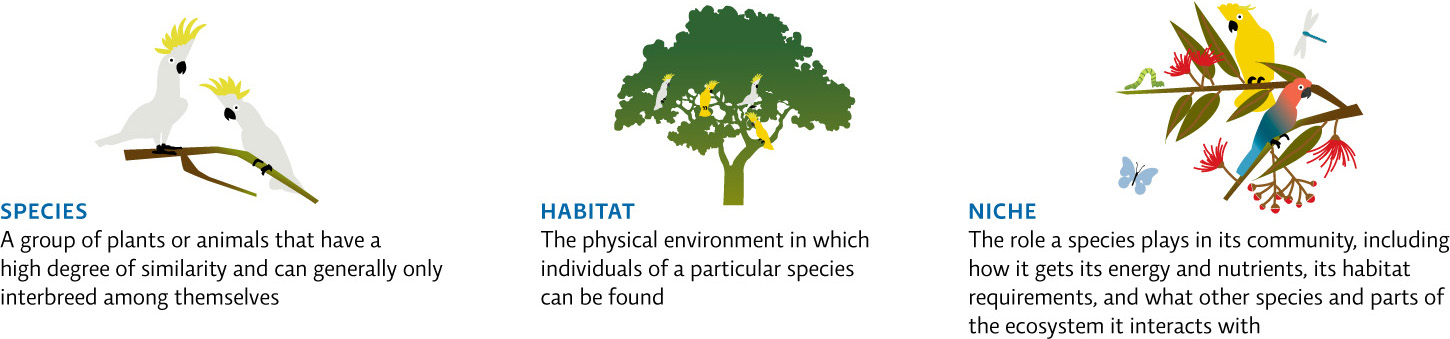

All ecosystems function through two fundamental processes that are collectively referred to as ecosystem processes, namely nutrient cycling and energy flow. Nutrient cycles are biogeochemical cycles that refer specifically to the movement of life’s essential chemicals or nutrientsthrough an ecosystem. Energy, on the other hand, enters ecosystems as solar radiation and is passed along from organism to organism, some released as heat, until there is no more usable energy left. Therefore we can say that matter cycles but energy flows in a one-way trip.

Earth—or “Biosphere 1,” as the creators of Biosphere 2 liked to call it—is materially closed but energetically open. [infographic 6.3] In other words, the plants and other organic material that make up an ecosystem, called biomass, cannot enter or leave the system, but energy can: some leaves as heat or light and new energy is absorbed from outside. In fact, plant biomass is produced with energy from the Sun through photosynthesis.

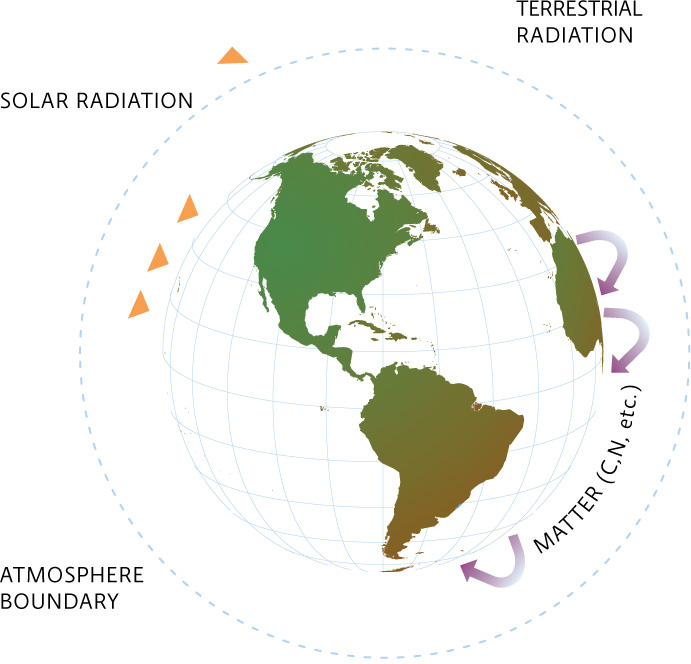

Biomes are specific portions of the biosphere determined by climate and identified by the predominant vegetation and organisms adapted to live there. Biomes can be divided into three broad categories—marine, freshwater, and terrestrial. Within those three categories are several narrower groups, and within those, a variety of subgroups. An entire biome itself may be considered an ecosystem, as are the smaller groups and subgroups. For example, forests, deserts, and grasslands are the three main types of terrestrial biomes. Within the forest biome category are different types of forests, such as tropical, temperate, or boreal forest, and within each of those groups are subgroups (for example, dry tropical forest and tropical rain forest.) [infographic 6.4]

When ecologists study entire ecosystems, they are limited to making observations and trying to discern cause and effect from those observations. This is no small challenge; even the simplest phenomenon is impacted by a myriad of factors. Precise, systemwide measurements are exceedingly difficult to come by. And unlike laboratory science, field research doesn’t often accommodate rigorous controls. Exceptions include whole-ecosystem research, such as that conducted at Canada‘s Experimental Lakes Area.

Biosphere 2 would offer ecologists an unprecedented research tool: a mini-planet where a variety of environmental variables—from temperature and water availability to the relative proportions of oxygen and carbon dioxide (CO2) at any given moment—could be tightly controlled and precisely measured. “Manipulating these variables and tracking the outcomes could greatly advance our understanding of natural ecosystems and all the minute, complex interactions that make them work,” says Kevin Griffin, a Columbia University plant ecologist who conducted research at the Biosphere 2 facility. “The plan was to use that knowledge to figure out how to repair degraded ecosystems in the real world, so that they continue to provide the services so essential to our survival.”

98

99

100

On top of all that, proving humans could survive in a completely enclosed, manufactured system would take us one giant step closer toward colonizing space.

But would it work?

The concept of enclosed ecosystems was not a new one. Since before they put a person on the moon, astronauts and engineers had been tinkering with their own artificial ecosystems—systems they hoped could one day be used to colonize space. The earliest versions of this technology were developed in the 1960s and 1970s by Russian and American scientists who, in the spirit of their times, had pitted themselves against one another in a mad dash to the finish line. The ecosystems they designed ranged from small, crude structures in which a single person might last for a single day, to larger, more sophisticated enterprises that could sustain a few people for a few months.

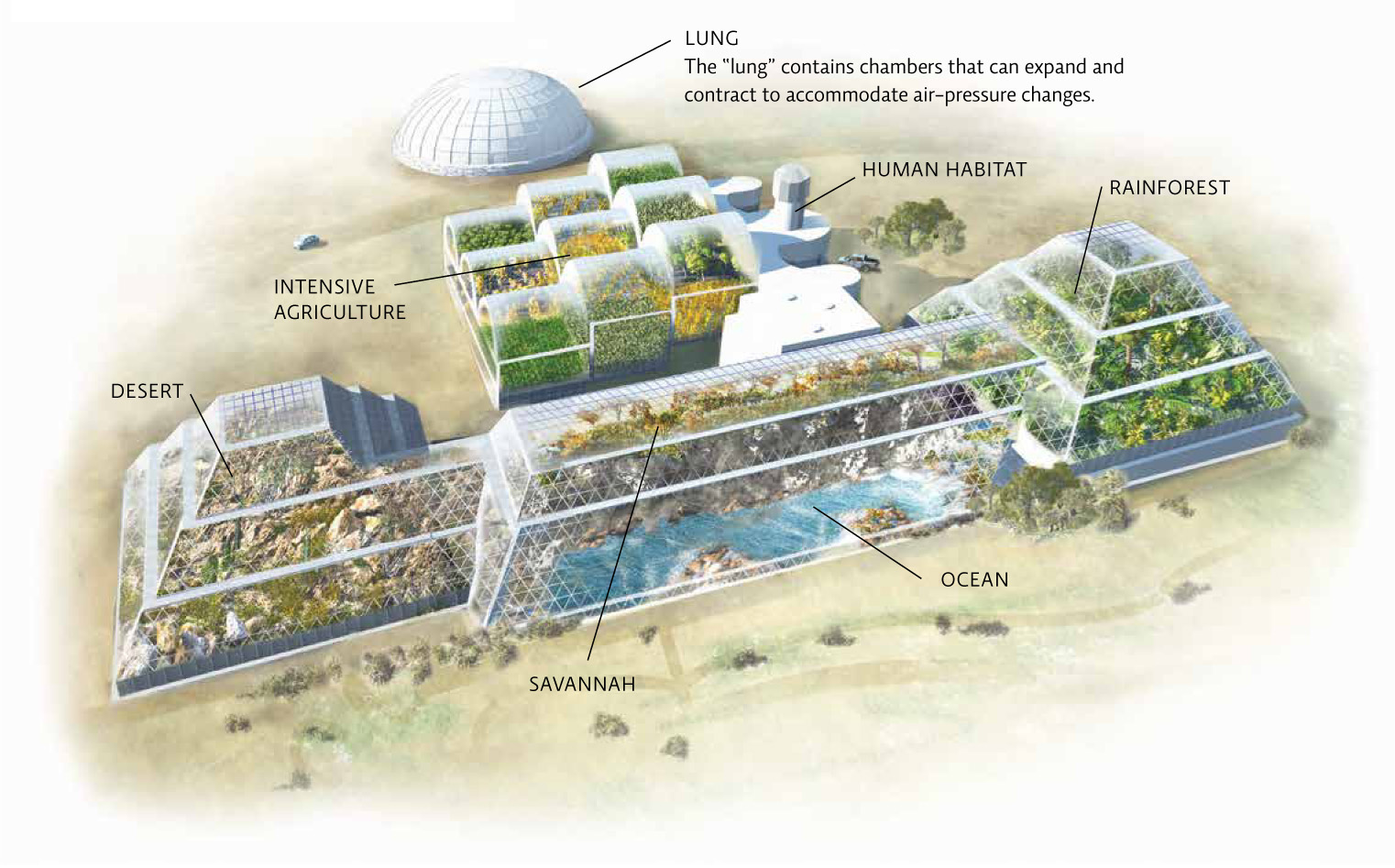

Biosphere 2 is by far the most elaborate. At just under 13 000 square metres, it remains the largest enclosed ecosystem ever created and the only one to house several biomes under one roof. [infographic 6.5] From a mountain under the dome’s 28-metre zenith, a stream rushes down through a tropical rainforest before snaking southward into a savannah. From there, the stream wends its way through a mangrove swamp into a 3.8 million-litreoceancomplete with a coral reef. On the other side of the ocean lies a desert. Biosphere 2 also includes a human habitat and an agricultural biome.

101