7.1 Endangered grey wolves return to the American West

| CHAPTER 7 | POPULATION ECOLOGY |

THE WOLF WATCHERS

112

113

CORE MESSAGE

Population size and makeup can fluctuate or remain stable. The stability of populations is often dependent on regulation by the environment or by other species like predators. If human impact has killed or removed predators, we may have to step in to fill their role.

GUIDING QUESTIONS

After reading this chapter, you should be able to answer the following questions:

What is a population and why is it an ecologically significant concept? What factors do ecologists use to describe and monitor natural populations?

What is a population and why is it an ecologically significant concept? What factors do ecologists use to describe and monitor natural populations? What types of population growth patterns are seen and what factors affect population growth?

What types of population growth patterns are seen and what factors affect population growth? What are the reproductive strategies of r- and K-selected species and how do these relate to population growth patterns and potential?

What are the reproductive strategies of r- and K-selected species and how do these relate to population growth patterns and potential? What is carrying capacity and why do some populations slowly approach it and then stabilize, whereas others overshoot it and then crash?

What is carrying capacity and why do some populations slowly approach it and then stabilize, whereas others overshoot it and then crash? What role do predators play in regulating populations and how can the presence or absence of predators affect entire communities?

What role do predators play in regulating populations and how can the presence or absence of predators affect entire communities?

114

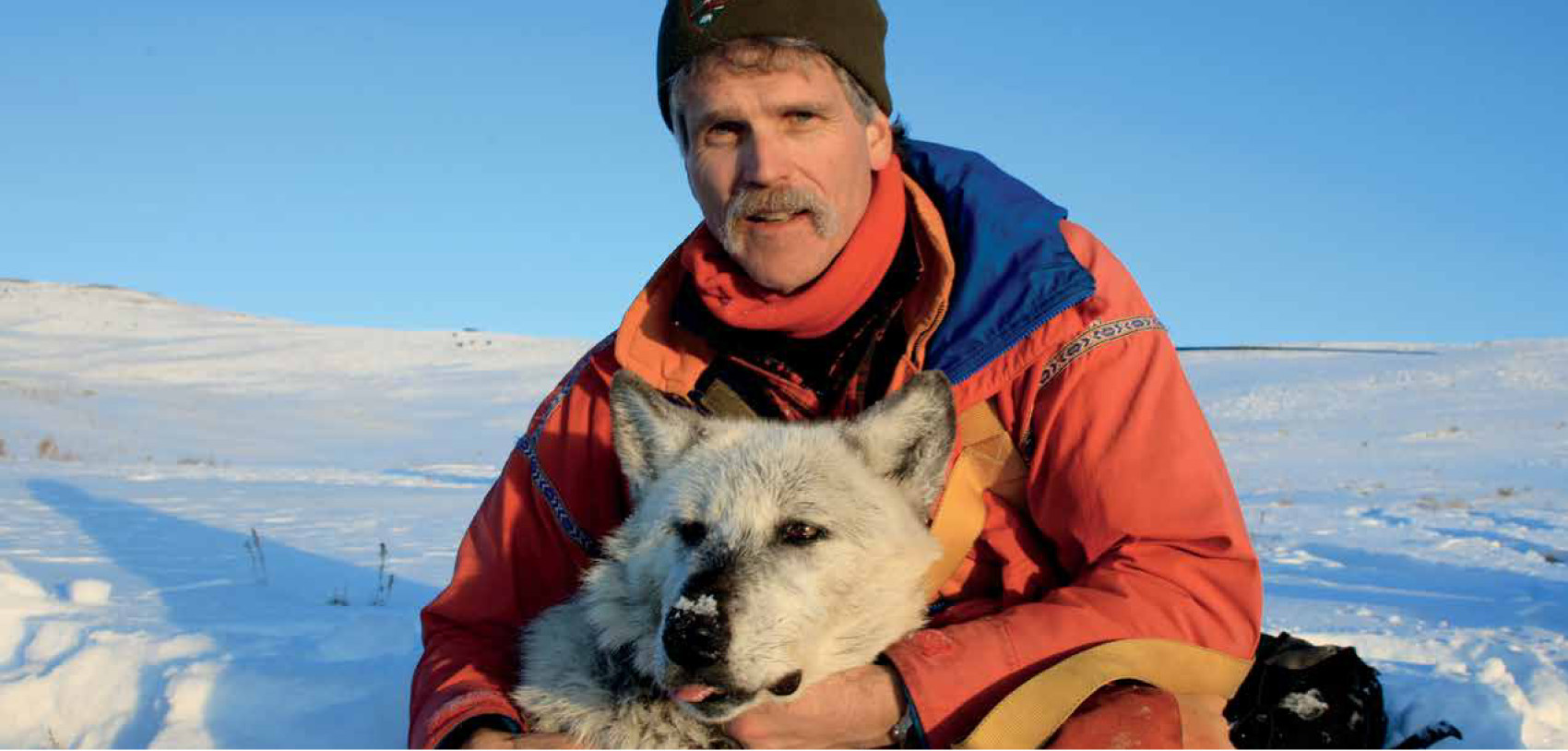

At least a half a dozen times each winter, Doug Smith climbs into a helicopter, gun in tow, and hunts wolves in Yellowstone National Park. He’s not looking to kill them—just to put them to sleep for a little while so that he can outfit them with radio collars to track the size of their packs, what they eat, and where they go over the course of the following year. Smith, a biologist, spends about 200 hours per year on these “hunting” expeditions, which are part of the Yellowstone Wolf Restoration Project that he leads. The project has been responsible for reintroducing many wolves to Yellowstone, after their numbers had dwindled to dangerous levels.

Sometimes, though, things go awry on Smith’s radio collar missions. For instance, the tranquilizer dart doesn’t fully sedate big wolves—some of which can reach 80 kilograms. Smith is forced to approach the animals while they’re still awake. “I have to grab them on the scruff of the neck and manhandle them until I get the collar on,” he explains. “They’re typically not dangerous then—they’ve had enough drug to be kind of out of it—but they’re still able to walk around. It’s a wild experience.” Sometimes the wolves—who are typically frightened of the helicopter—try to attack it while it’s hovering with the doors open a couple metres above the ground. “I’ve had two females turn and run at the helicopter, teeth gnashing, jumping up trying to get me,” Smith recalls. “I’m hovering above a wolf going back and forth, and I can’t get a shot because all I’m seeing is face and teeth.” Despite these adventures, Smith says a wolf has never actually bitten him—and he has tranquilized and collared more than 300 of them.

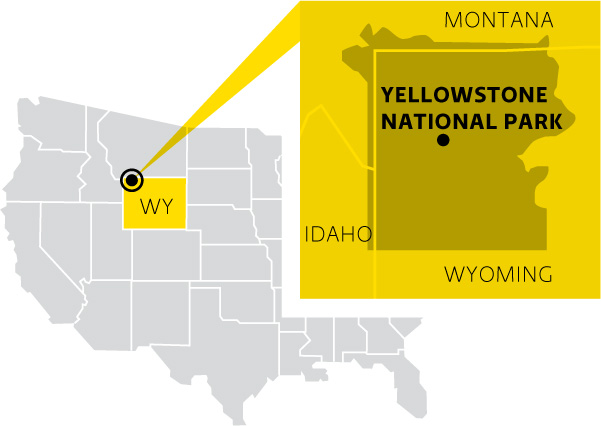

Where is Yellowstone National Park?

Understanding how wolf populations interact with biotic and abiotic forces in their environment, through programs like the Yellowstone Wolf Restoration Project, is key to preventing this vital species from disappearing from Yellowstone Park—and the United States—forever. That’s because so many factors influence the livelihood of a species and its ability to survive and reproduce. In the early 20th century, Americans in western states not only threatened wolves by hunting them, but they also destroyed the animals’ natural habitat when they cut down forests to build farms. They also starved the animals by hunting elk, deer, and bison, wolves’ usual sources of food. At the time, people didn’t think that this combination of changes would very nearly cause wolves to go extinct. But now that scientists like Smith have spent years watching how the animals live, they have a much better understanding of what needs to be done to keep them alive and maintain them at their natural population numbers. Today, such efforts are more crucial than ever, with more than 20 000 plant and animal species categorized as threatened on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN’s) Red List of Threatened Species.

Before a U.S. government-sponsored wolf control program began in the early 1900s, the exact numbers of grey wolves living in Yellowstone were unknown, but estimates range from 300 to 400. Chances are, their numbers fluctuated over time. Canadian grey wolves are faring reasonably well. With an estimated 50 000 wolves living across the country, Canada has the second largest wolf population in the world after Russia. A population—all the individuals of a species that live in the same geographic area and are able to interact and interbreed—frequently fluctuates in size and distribution. So, although the Canadian wolf population is relatively stable, it does fluctuate with changes in such factors as access to food, water, and den sites, the presence of predators (including humans, who affect population stability through hunting and fishing), as well as the population’s innate characteristics. Ecologists, and population biologists (like Smith), who study changes in population size and makeup (population dynamics), find that the population size of some species increases and decreases rather predictably (barring a catastrophic event), while others tend to fluctuate more randomly. The size of a population in a given area is determined by the interplay of factors that simultaneously increase the number of individuals in a population (births and immigration), and those that decrease numbers (deaths and emigration). An understanding of these factors helps us predict population size at any given time.

115