7.2 Populations fluctuate in size and have varied distributions.

In the early 20th century, the U.S. government began its Predator Control Program, for which the U.S. Congress allocated $125,000 for predator and rodent control through poisoning—and later through hunting—to eradicate or control wild animals that might harm crops or livestock. Wolves were a targeted predator because they preyed upon livestock, and wolf eradication was further supported because it boosted deer populations for human hunting. The U.S. National Park Service herded wolves out of parks so they could be hunted; moving them outside made them more accessible to hunters and made the parks more welcoming for visitors. “It was park policy to kill all predators, and wolves were their biggest objective,” Smith explains. Between 1914 and 1926, at least 136 wolves were killed within Yellowstone. The last known Yellowstone wolf was killed in 1944.

Every population has a minimum viable population, or the smallest number of individuals that would still allow a population to be able to persist or grow, ensuring long-term survival. This is an important concept when considering how to conserve endangered or threatened species. A population that is too small may fail to recover for a variety of reasons. For example, the courtship rituals of some species require a minimum number of individuals for success. Other activities that depend on numbers—like flocking, schooling, and foraging—fail below certain population sizes. Genetic diversity (inherited variety among individuals in a population) is also important: a population with little genetic diversity is less able to evolve new traits that enable them to adapt to environmental changes and is therefore more vulnerable. A small population is also subject to inbreeding, which allows harmful genetic traits to spread and weaken the population.

116

In the American West, the Predator Control Program was so successful that it eventually became cause for concern and criticism as populations were close to or below minimum viable thresholds. In 1973, wolves in Montana and Wyoming became protected under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. In 1987, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service proposed reintroducing an “experimental population” of Canadian wolves into Yellowstone through its Northern Rocky Mountain Wolf Recovery Plan.

Not everyone was in favour of reintroducing wolves to the landscape of the American West, and opposition remains today. Ranchers in particular were (and still are) wary of the damage wolves might do to livestock. In some years, wolves were responsible for thousands of herd deaths—although not nearly as many as are caused by coyotes, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Current programs compensate ranchers for lost livestock, but they must first prove that the animal was killed by a wolf, which is not always easy to do. Sport hunters worry that wolves will decimate game species like deer and elk; however, these animals succumb to many factors, including bad weather and other predators—not just wolves—so it is unclear how much pressure wolves actually put on these species.

The U.S. Congress funded the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to conduct an environmental impact assessment on the local environment should wolves be reintroduced to Yellowstone. By considering all aspects of wolf ecology, scientists were able to organize the reintroduction to maximize survival of the species. For instance, scientists believed that it would be best to “softly” release wolves in the park by holding them temporarily in packs in areas that would be suitable for them to live, instead of doing a “hard” release in which the wolves could immediately disperse anywhere in the park. The soft release would curtail the wolves’ movement and help them survive and acclimate to the move. In addition, it would allow the park staff, who would bring road-killed deer, elk, moose, and bison to the wolves twice a week, to become familiar with the wolves so that they could identify them once they were fully released. In January 1995, scientists captured 14 wolves from different packs across Canada, and softly released them into Yellowstone.

The number of wolves distributed across Yellowstone Park is their population density—the number of individuals per unit area. Population density is an important feature that varies enormously among species, or even among populations of the same species in different ecosystems. If a population’s density is too low, individuals may have difficulty in finding mates, or the only potential mates may be closely related individuals, which can lead to inbreeding, loss of genetic variability, and ultimately, extinction. Density that is too high can also cause problems, such as increased competition, fighting, and spread of disease. Deer and elk populations in the United States and Canada, whose density had increased in recent years because of exploding numbers combined with shrinking habitats, now frequently suffer from an infectious disease known as chronic wasting disease, which weakens and eventually kills the animals.

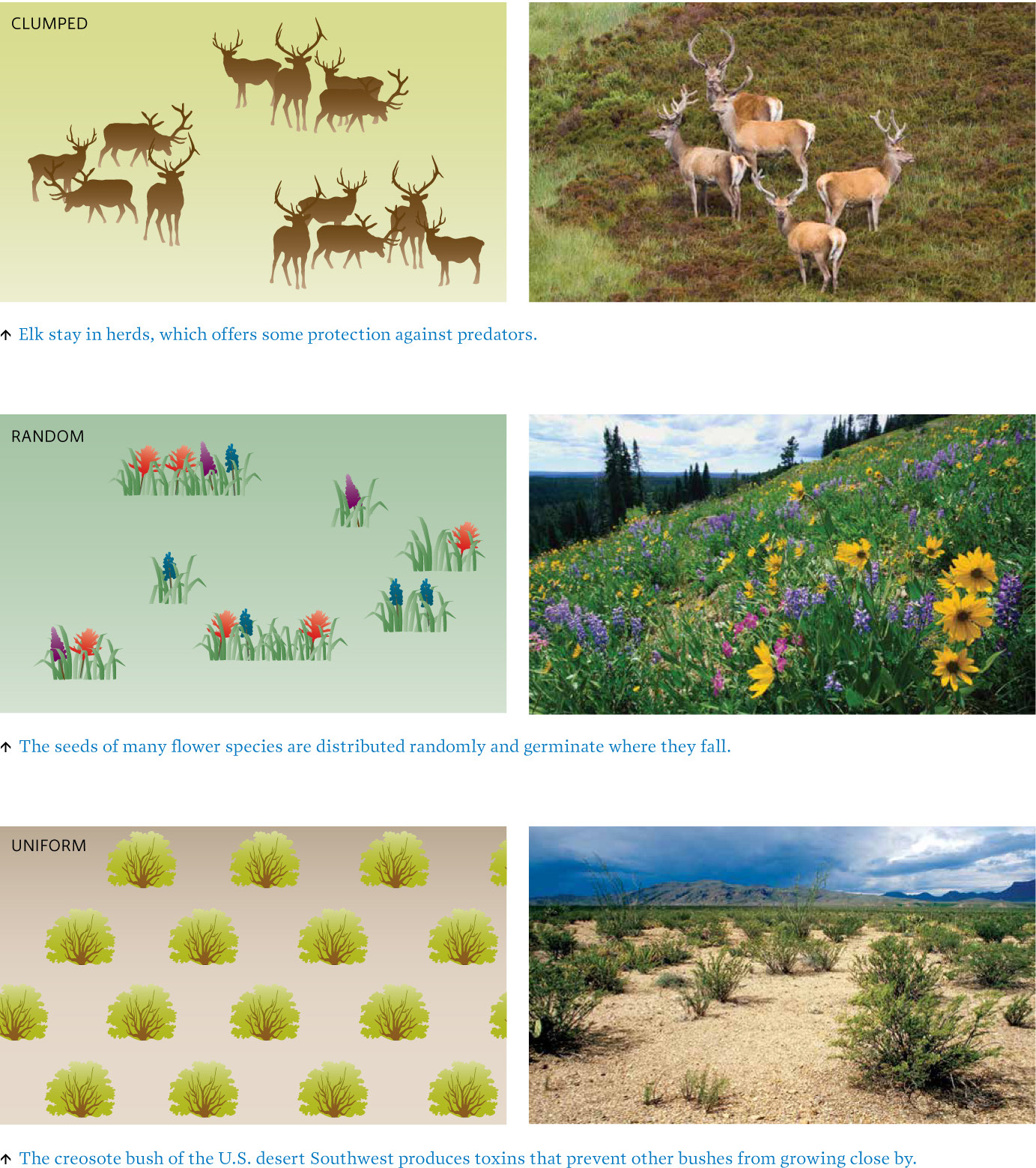

In addition to size and density, another important feature is population distribution, or the location and spacing of individuals within their range. A number of factors affect distribution, including species characteristics, topography, and habitat makeup. Ecologists typically speak of three types of distribution. In a clumped distribution, individuals are found in groups or patches within the habitat. North American examples include social species like prairie dogs or beaver that are clustered around a necessary resource, like water. Wolves travel in packs and therefore have a clumped distribution. Elk, one of their prey species, congregate as well; living in herds offers some protection against the wolves.

In a random distribution, individuals are spread out in the environment irregularly with no discernible pattern. Random distributions are sometimes seen in homogeneous environments, in part because no particular spot is considered better than another. Species that disperse through random means and germinate where they fall—like wind-blown seeds—also often distribute randomly. Uniform distributions, rare in nature, include individuals that are spaced evenly, perhaps due to territorial behaviour or mechanisms for suppressing growth of nearby individuals (seen in some plant species). [infographic 7.1]