7.5 The loss of the wolf emphasized the importance of an ecosystem’s top predator.

Thanks in part to Smith’s determination, the Yellowstone Gray Wolf Restoration Project has been incredibly successful. There are now more than 5000 of these wolves living in the contiguous United States, approximately 100 of which are in Yellowstone National Park. But one chief lesson hammered home by observing wolves in Yellowstone is that populations do not exist in isolation. “Work in central Yellowstone clearly demonstrated that the addition of a keystone species, such as wolves, can result in observable changes in the behaviour of its prey,” says Claire Gower, a wildlife biologist at Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks. “These consequences may not stop at the prey individual, but may have cascading effects on other community-level processes.” After wolves were reintroduced to Yellowstone, scientists noticed that coyote populations in the area shrank, in part because the wolves were hunting them. This has had a cascade of effects on the other smaller mammals upon which coyotes typically prey. For instance, scientists speculate that the elusive red fox—whose nocturnal behaviour makes these foxes difficult to track—has probably become more common in the park, because fewer coyotes are around to hunt them, and because foxes do not share any prey with wolves.

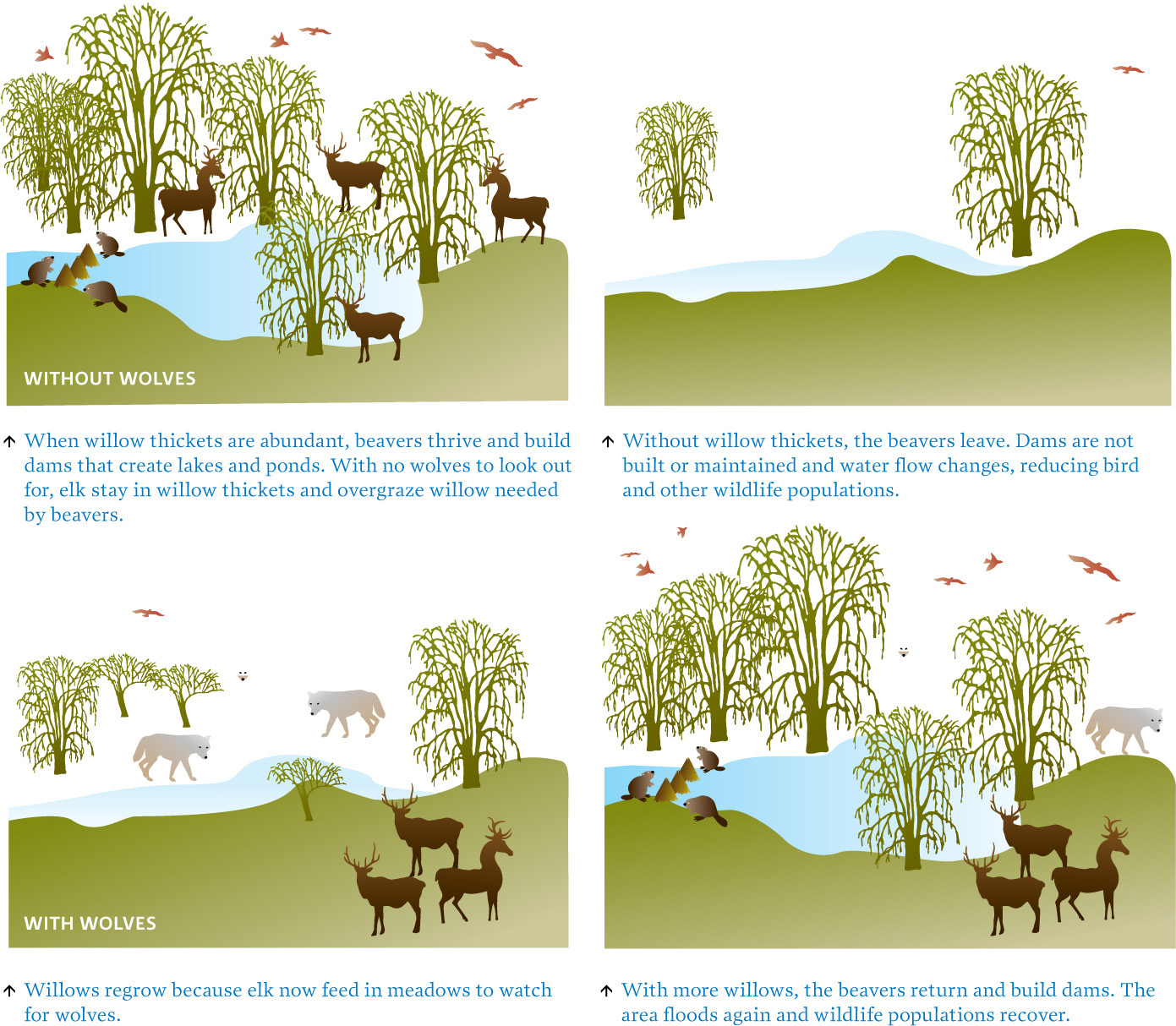

The elk population has also been affected. According to the U.S. National Park Service, the elk population in Yellowstone doubled between 1914 and 1932 as a direct result of wolf extirpation (local extinction). These elk then began exerting pressure on their food sources. Willow trees were overgrazed because elk like to eat the tender young shoots; this removed an important resource for other animals like birds (habitat) and beaver (food and building material). The decline of the beaver population was especially significant because beaver dams change the flow of water, creating lakes that support a wide variety of fish, amphibian, and plant species that would not frequent faster-flowing streams. The loss of these dams allowed streams to return to their original flow, altering the community that lived in the area.

123

“Work in central Yellowstone clearly demonstrated that the addition of a keystone species, such as wolves, can result in observable changes in the behaviour of its prey.”—Claire Gower

As the wolf population increased again after reintroduction, the elk spent less time in willow stands, preferring to be out in the open where they could see their predators. As the willows recovered, so did songbird populations. Beavers returned as well, and their dam-building restored lakes and fish populations. Damming the river also slowed the flow of water enough to increase the amount that soaked into the ground, recharging groundwater supplies and providing more water for the deep roots of trees. Populations interact with their ecological community in complex and often unpredictable ways. [infographic 7.7]

Ecologist and environmentalist Aldo Leopold, who lived in the early 20th century, was one of the first conservationists concerned with the effect of eliminating the wolf from the American West. He recognized that the problems resulting from interference with ecological communities could be far-reaching. “I now suspect that just as a deer herd lives in mortal fear of its wolves, so does a mountain live in mortal fear of its deer,” he wrote in his book A Sand County Almanac. “And perhaps with better cause, for while a buck pulled down by wolves can be replaced in two or three years, a range pulled down by too many deer may fail of replacement in as many decades.”

Many populations of animals other than wolves are declining worldwide due to human impact, especially from habitat loss, the introduction of non-native species, and predator removals. The number one reason that species become endangered is habitat destruction. People alter or destroy habitats or resources, breaking needed connections within ecosystems, and populations respond. Some species may benefit from the change and their population could increase (purple loosestrife, a non-native plant, spreads quickly in wet roadside ditches across Canada). Other species may decline in number because they are displaced by others, or because needed conditions for growth are no longer present (songbirds may lose habitat if the woodland patches they nest in are cut down). Understanding community interactions and population dynamics helps managers monitor, protect, and restore populations.

124

Often these dynamics are complex. For instance, while many people believe that the Wolf Restoration Project is the sole cause of Yellowstone’s recent elk population decline—the reintroduced wolves, they say, are simply eating all the elk—in reality, many factors have played a role in the decline. “Wolves have come back, cougars have come back, the state was managing for fewer elk by hunting them when they left the park, and grizzly and black bears increased in number, which eat elk calves too,” Smith explains. “There are many reasons why they’ve declined.” Some studies suggest that winter weather may be one of the main factors that control elk and deer population sizes. To ensure that a population survives, it is crucial that managers assess all of the possible reasons for a population’s changes.

125

The success of the reintroduction program has led to the wolf being “delisted” in Montana and Idaho (its status has been changed from “endangered” to “threatened”), though not without opposition from some conservation groups. This delisting has the potential to allow wolf hunts with quotas set by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, similar to those allowed in Canada. But even if wolf populations become stable, biologists will have to continually manage them so that they stay that way. Many provinces and territories have wolf management plans that focus not only on maintaining healthy populations, but also on controlling their numbers to prevent conflicts with humans and on protecting prey such as caribou. The Yukon Wolf Management Plan, for instance, recognizing that wolves are a renewable and currently stable resource in that area, identifies hunting and trapping as legitimate activities (except when nursing pups are present); it reports that 2–3% are killed annually but that as much as 30% of the population could be taken without compromising the population’s conservation status. The British Columbia Wolf Management Plan has no limits on hunting wolves in areas where livestock are at risk. Wolf hunting has become a major sport in Canada, but not surprisingly it has its critics, who are opposed to killing wolves and want to encourage wolf viewing as a form of ecotourism.

To ensure that the wolves reintroduced to Yellowstone are given the chance to really flourish, Smith and his colleagues diligently stay on the wolves’ trail, studying their population dynamics. “We want to know their population size, what they are eating, where they are denning, how many pups they have and how many survive, and how the wolves interact with each other,” he explains. Why is it so important to ensure that the wolves do well? Simply put: they were here first, he says. “We want to restore the original inhabitants to the Park.”

Select references in this chapter:

Beyer, H.L., et al. 2007. Ecological Applications, 17: 1563–1571.

Krebs, C.J. 2010. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 278(1705): 481–489.

Vucetich, J.A., and Peterson, R.O. 2004. Proceedings of the Royal Society London Biological Sciences, 271: 183–189.

BRING IT HOME: PERSONAL CHOICES THAT HELP

Understanding the factors that influence how populations change can help us manage species that are either becoming invasive in nature or are facing extinction. How people view species and their connection to our world has a large impact on how management plays out.

Individual Steps

Learn more about wolves at the International Wolf Center (www.wolf.org).

Learn more about wolves at the International Wolf Center (www.wolf.org).

Use the Internet and books on wildlife to research what your area might have been like prior to human settlement. Which species have been extirpated; which ones have been introduced? How have wildlife populations changed as a result of human action?

Use the Internet and books on wildlife to research what your area might have been like prior to human settlement. Which species have been extirpated; which ones have been introduced? How have wildlife populations changed as a result of human action?

See if you can recognize distribution patterns in the wild. Do some flowers or trees grow in clumps or patches? Can you find species that appear to have a random or uniform distribution?

See if you can recognize distribution patterns in the wild. Do some flowers or trees grow in clumps or patches? Can you find species that appear to have a random or uniform distribution?

Group Action

Explore organizations that support predator preservation, such as Defenders of Wildlife and Keystone Conservation, for suggestions on how you can help educate others about the importance of predators.

Explore organizations that support predator preservation, such as Defenders of Wildlife and Keystone Conservation, for suggestions on how you can help educate others about the importance of predators.

Join a local, regional, or national group that works to monitor, protect, and restore wildlife habitats, such as the Nature Conservancy of Canada’s Conservation Volunteers.

Join a local, regional, or national group that works to monitor, protect, and restore wildlife habitats, such as the Nature Conservancy of Canada’s Conservation Volunteers.

Policy Change

Caribou (Rangifer tarandus) is an iconic Canadian species that is currently listed as threatened under Canada’s Species at Risk Act. In Banff National Park, falling caribou numbers are linked to rising wolf populations brought on by high elk populations. Reintroduction of caribou has been proposed using captive-bred animals. Research the issue and write a letter to Parks Canada that reflects your position on this proposal.

Caribou (Rangifer tarandus) is an iconic Canadian species that is currently listed as threatened under Canada’s Species at Risk Act. In Banff National Park, falling caribou numbers are linked to rising wolf populations brought on by high elk populations. Reintroduction of caribou has been proposed using captive-bred animals. Research the issue and write a letter to Parks Canada that reflects your position on this proposal.

126